Have you ever started looking for something, only to find something else that was more interesting than what you were originally looking for?

Back on 10 January 2014, there were widespread rumors of a significant aurora event that would be visible much further south than usual. It got a lot of people excited, even in our backyard here in Colorado. But did it happen?

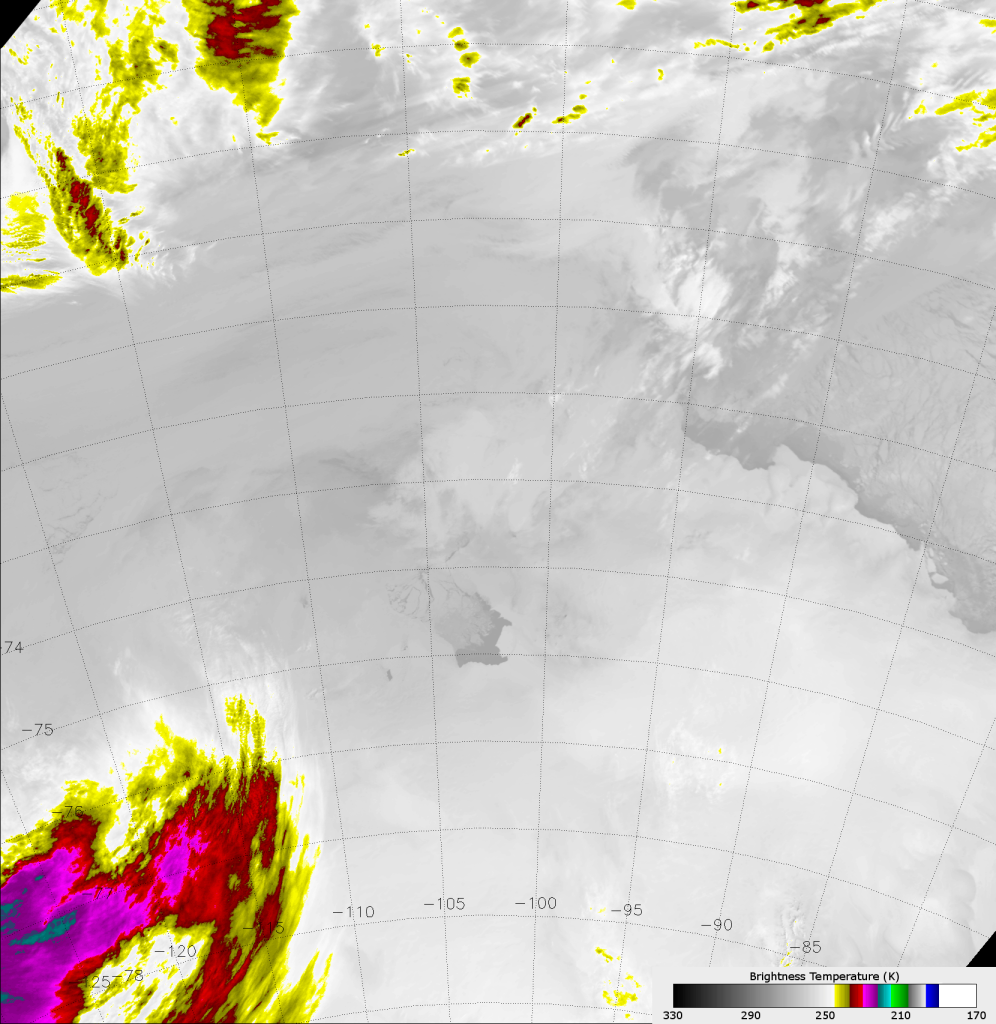

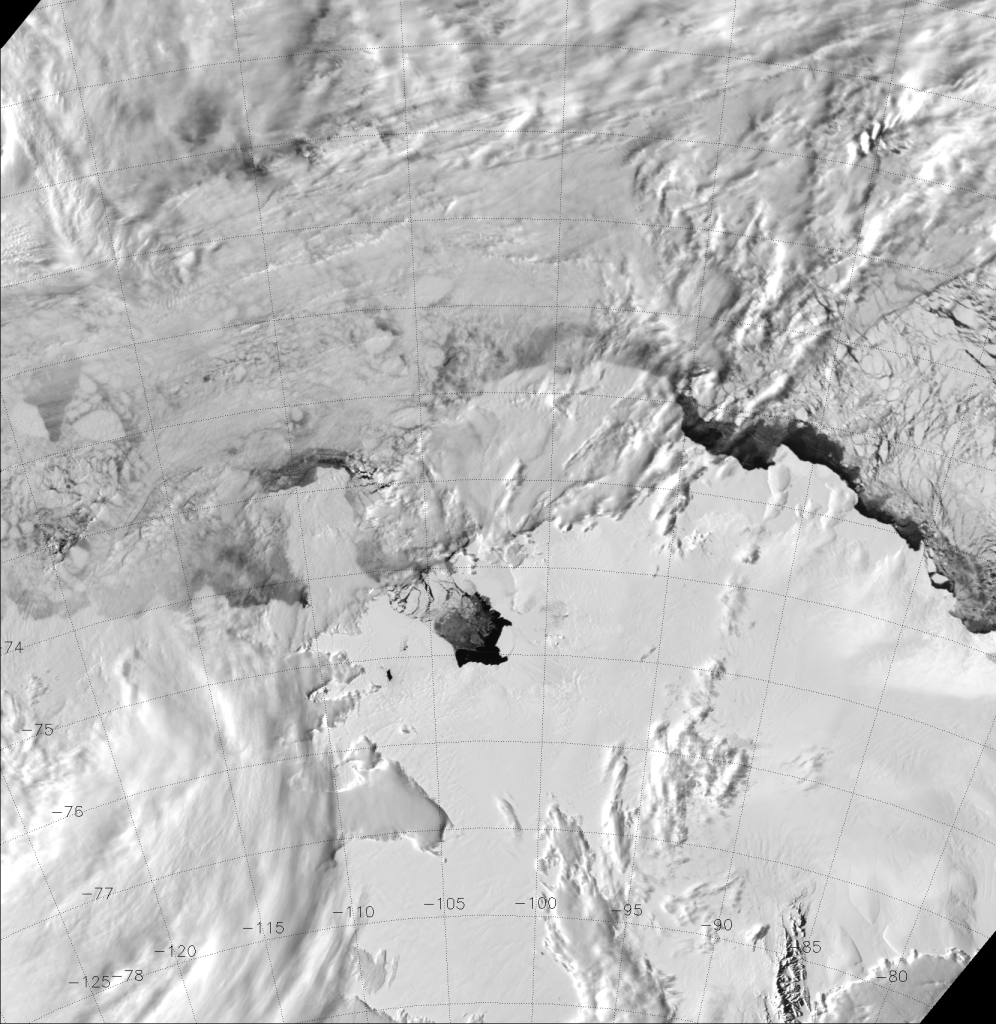

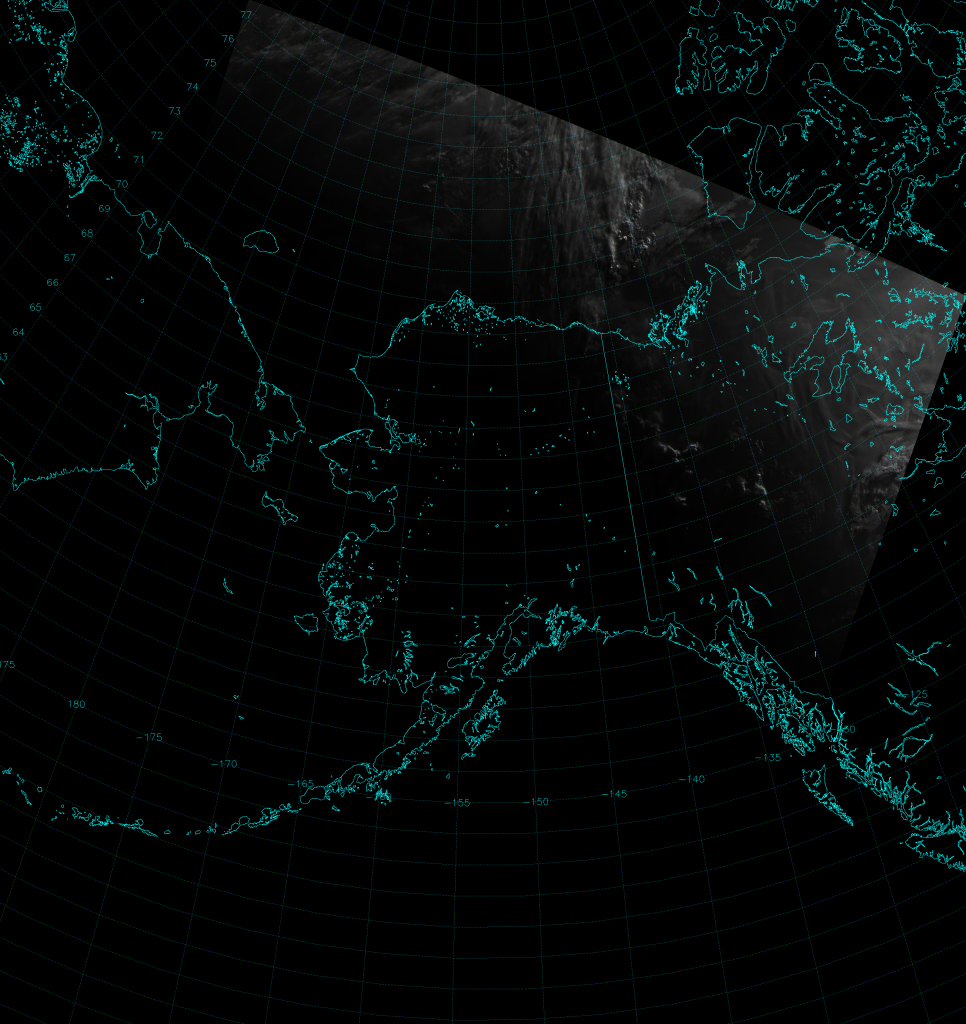

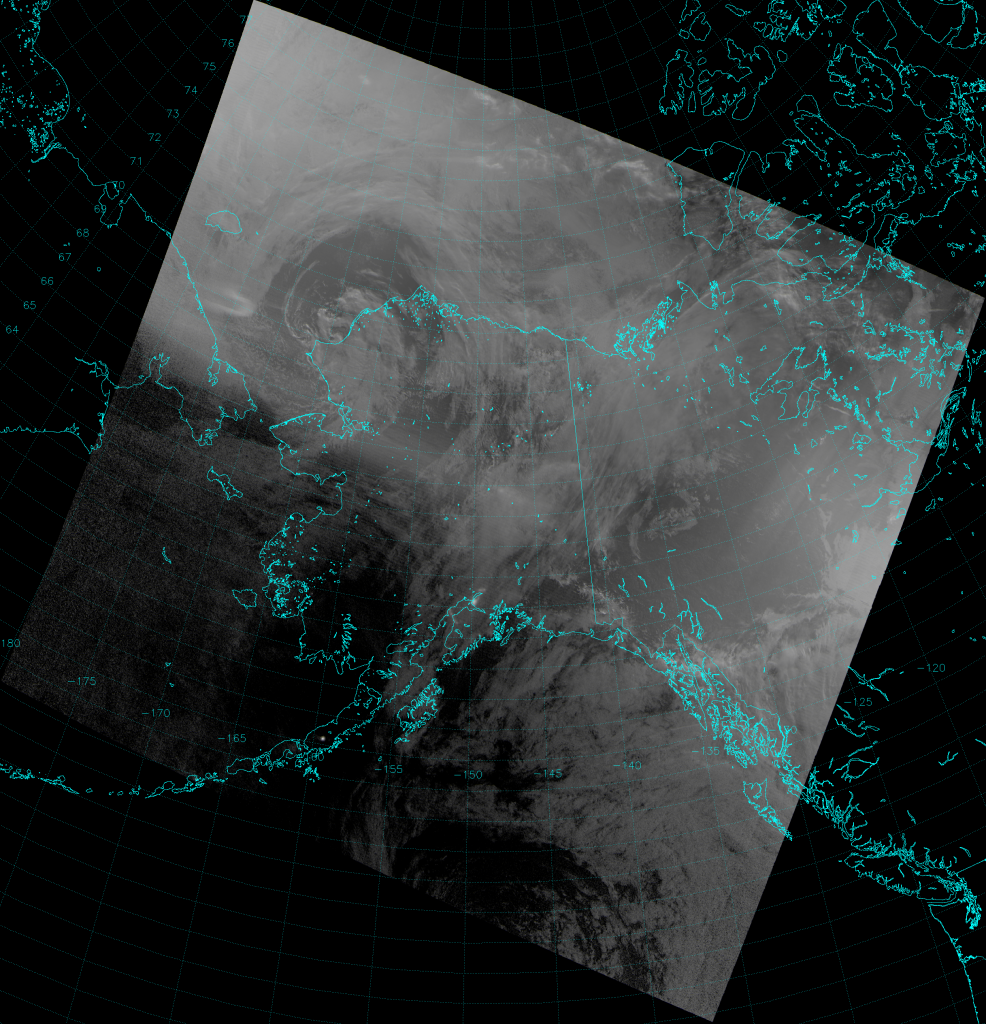

If you’re curious, here is an explanation as to why the aurora forecasts were a bust. But, that’s not to say the aurora didn’t exist anywhere on the globe. The VIIRS Day/Night Band image below shows there was an aurora that made it as far south as Iceland.

What about on the next orbit? Was the aurora still there?

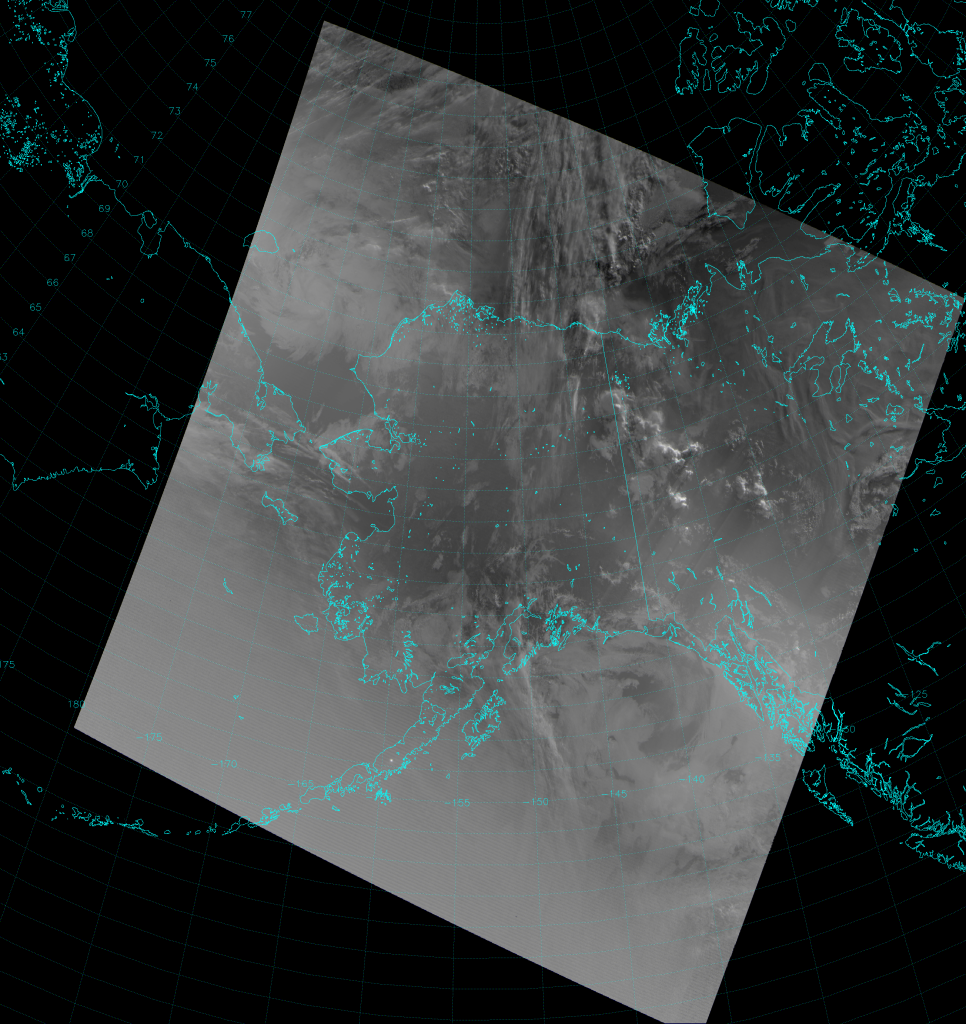

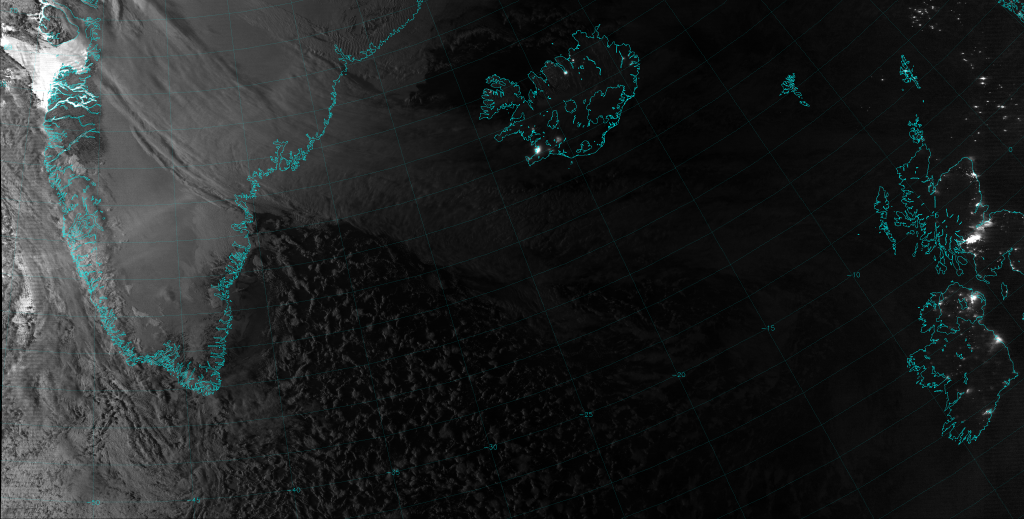

If you squint, you can maybe see it over south-central Greenland. But, hold on a minute! What’s that in the upper-left corner? Why is the water so bright off the west coast of Greenland?

This is a nighttime scene, as evidenced by the city lights over Iceland, Ireland and the UK, although you might not think that by looking at only the left side of the image. And, let me assure you, the day/night terminator never appears at this angle at this time of day in January.

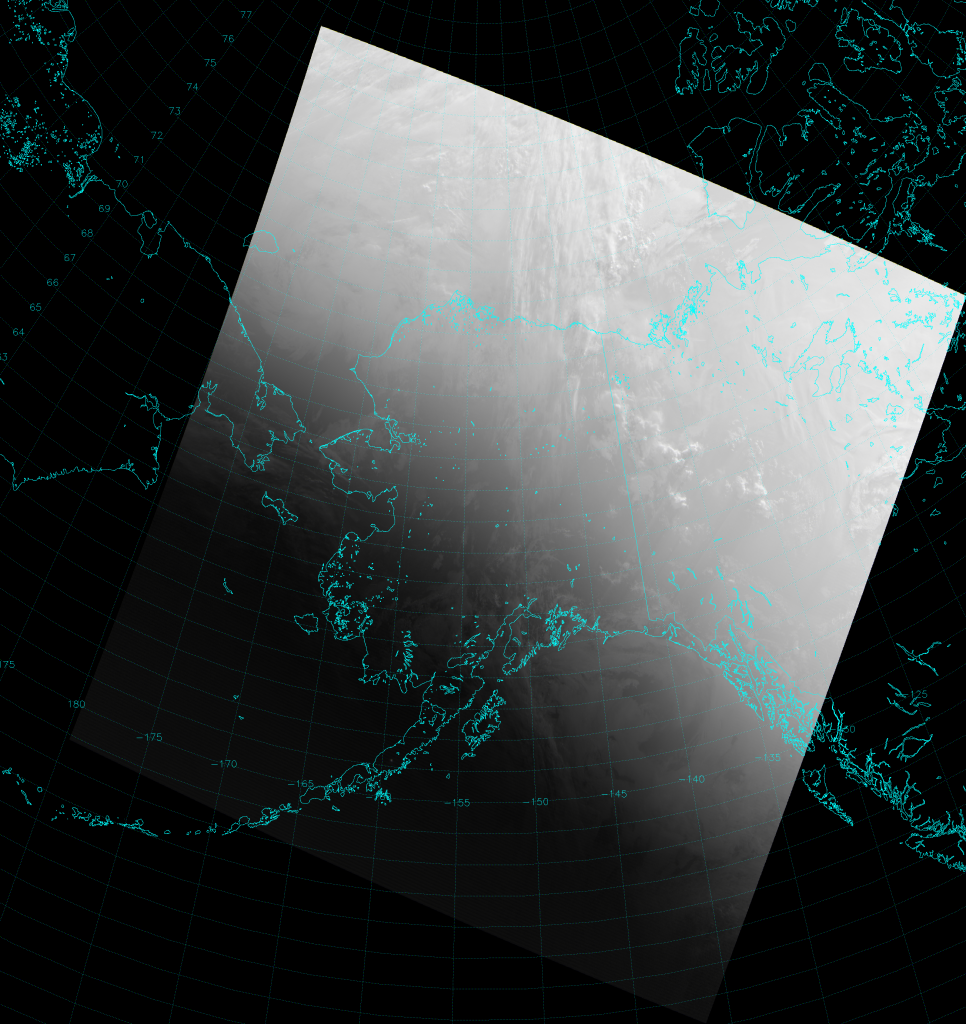

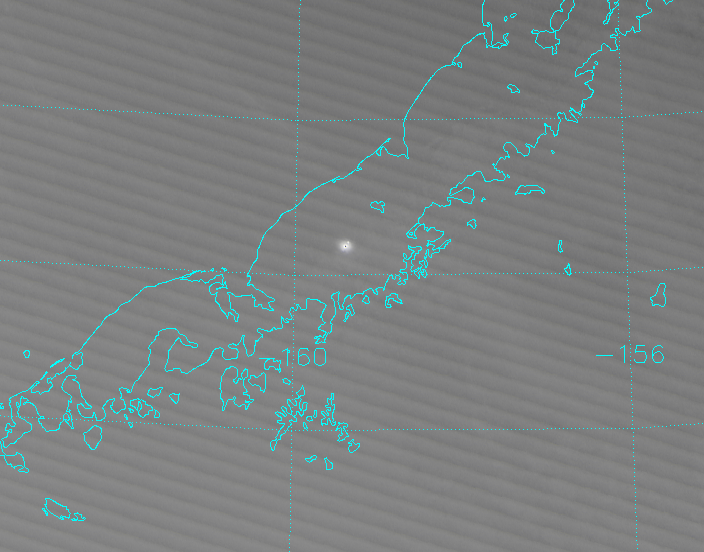

CIRA researchers have recently begun producing VIIRS imagery centered on Alaska on a quasi-operational basis. About a month ago, I noticed this image that also shows “glow-in-the-dark” water, and the mystery deepened:

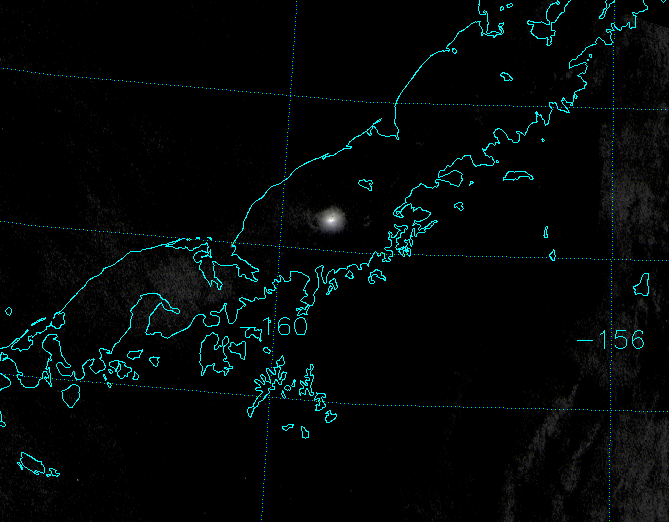

And again, a few days ago, the Day/Night Band captured this image:

This time, there is a pretty vivid aurora but, you can also see bright water off the southern coast of Russia. So, what’s with water that appears to be glowing in the dark?

Is it some kind of bio-luminescent phenomenon, like milky seas? Is it some kind of radioactivity that makes everything glow, like in The Simpsons? Or an alien-UFO conspiracy to control the world’s population?

Sorry to get your hopes up, “truthers,” but it’s a pretty mundane explanation. (Either that, or I’m a member of the Illuminati. MWAH HA HA!) Have you ever looked at a body of water and saw glare from the sun? Or seen glare off of snow and ice? We call that sunglint. It is related to the Bi-directional Reflectance Distribution Function (BRDF), the mathematical way we describe that incoming light on a surface reflects more at certain angles than others. But, it’s not only sunlight that causes glint. Moonlight does it, too. (What is moonlight, if not reflected sunlight?)

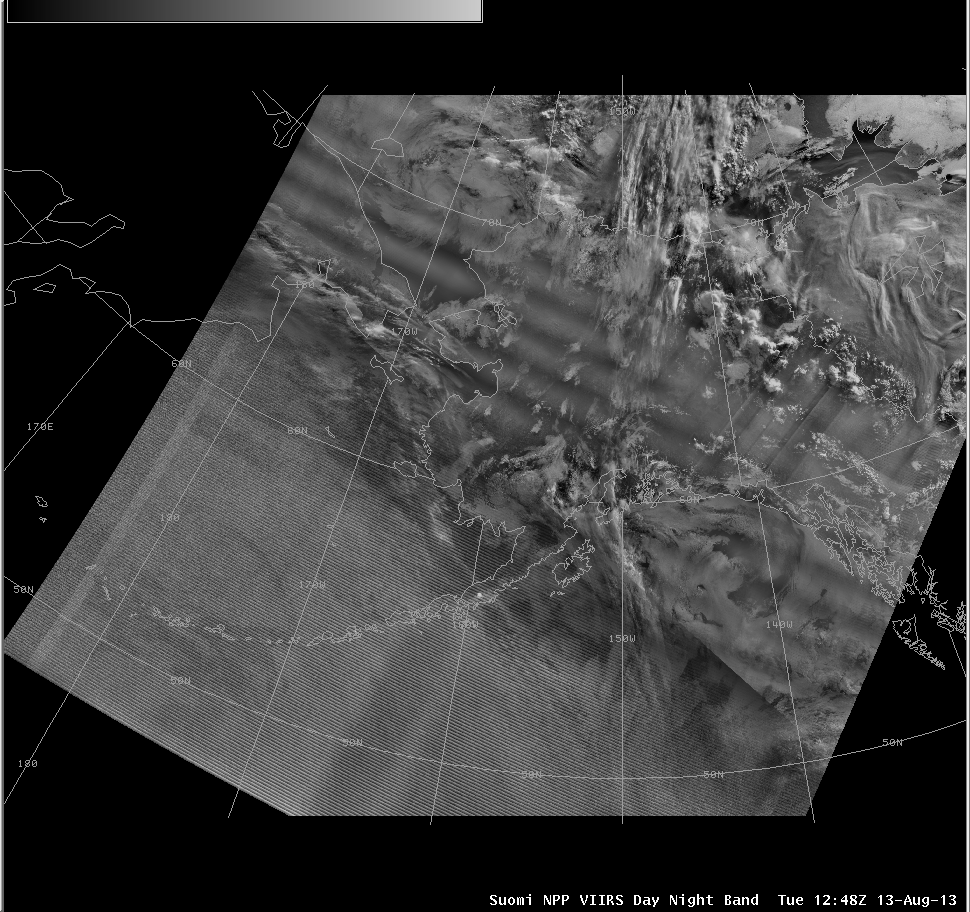

Notice that the images with the glowing water were taken roughly a month apart. That’s not just a coincidence. According to this website, each of those images was taken 2-3 days after the moon reached first quarter, when the moon was 75-80% full. Why is this important? Because the phase of the moon is related to when the moon rises and sets, and this determines where the moon is in the sky when VIIRS passes overhead.

From a day or two after last quarter to new moon to a day or two after first quarter, the moon is below the horizon when VIIRS passes overhead during the nighttime overpass. (It’s above the horizon on the daytime overpass, but you can’t tell because the sun is so bright.) From just after first quarter to full moon to just after last quarter, the opposite is true – the moon is up at night and down during the day. When you get to 2-3 days after first quarter, that’s when the moon is close to the western horizon when VIIRS passes over at night. That’s why the left sides of the above images are brighter than the right sides. And, that’s also when this form of moon glint occurs, just like in this clip.

It’s not aliens or UFOs or mysterious radioactivity. It’s the geometry between the satellite, the Earth and the moon and the preferential reflection of light off of a body of water. It’s repeatable and predictable. It’s science.

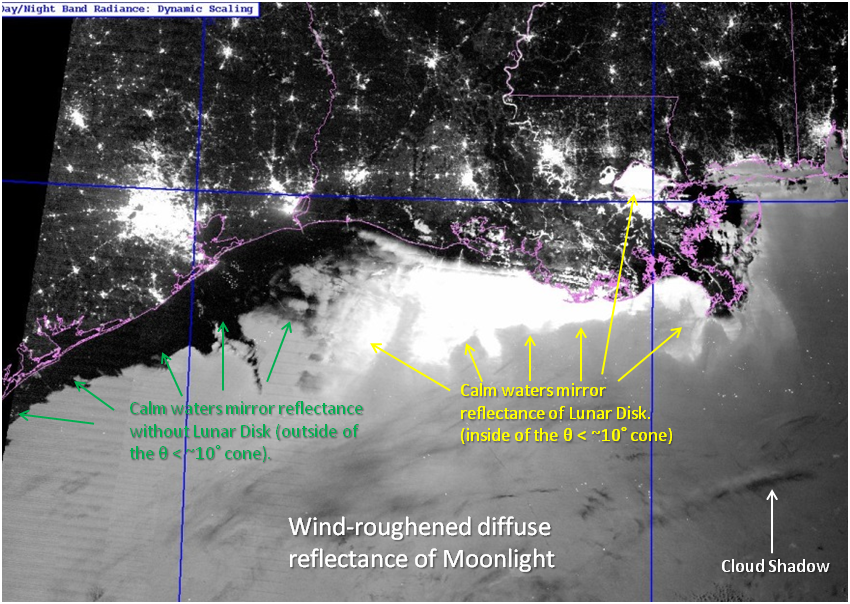

UPDATE (3/14/2014): “Glow-in-the-dark” water is not confined to high latitudes like Greenland and Alaska. It happens anywhere the angle between the satellite, the Earth’s surface and the moon is in the glint range. Steve Miller (CIRA) forwarded information about a case he looked at off the coast of Louisiana. Here’s one of his images with everything labelled:

This case occurred when the moon was 90% full. The brightest water occurs where the surface is calm and the “glint angle” is less than 10°. When the surface is not calm, waves scatter the light in different directions and only a portion of the light is reflected to the satellite. This makes the water appear not as bright. For glint angles between 0° and 30°, waves will scatter some of the light back to the satellite, and the water won’t appear dark. Calm water outside the 10° glint zone will appear dark, though, because the angle of the water surface isn’t right to reflect the moonlight back to the satellite. This is what you see along the coast of Texas. Outside of the 30° zone, waves aren’t at the proper angle to reflect light back to the satellite.

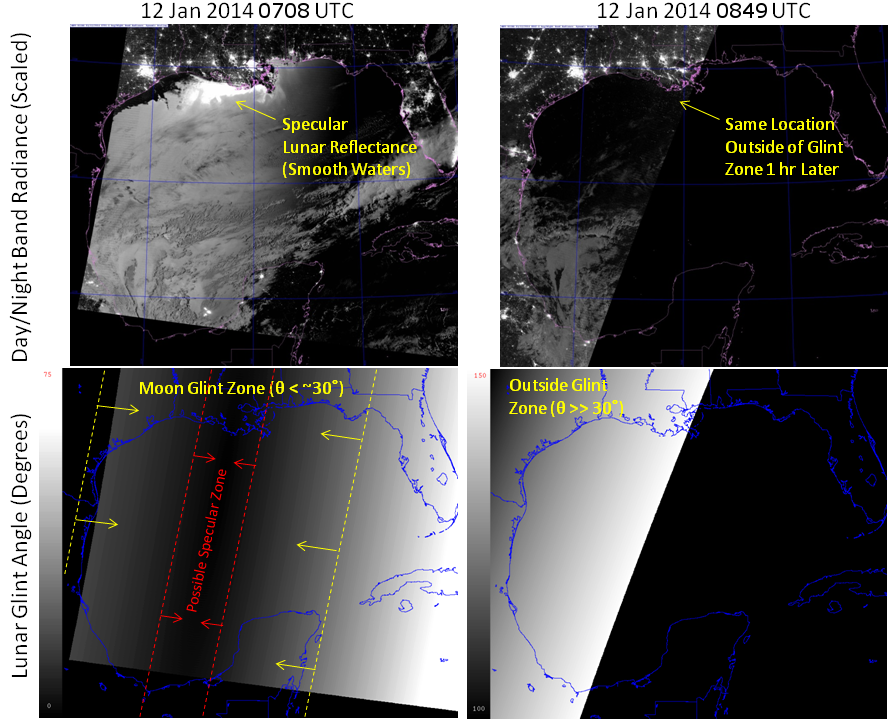

To demonstrate this, here’s a comparison with the same area on the next orbit along with the glint angles:

On the next overpass, about 100 minutes later, all the water is outside the glint zone (the glint angles are all higher than 100°) and the water is dark everywhere, as expected.