Do rocks float? The answer to that is “Depends on which rocks you’re talking about.”

We just looked at what happens in the atmosphere when a volcano like Copahue erupts. We also looked at the impact the 1912 eruption of Novarupta still has today. And, before VIIRS was launched into space, there was Eyjafjallajökull – the Icelandic volcano that nobody could pronounce. (Think “Eye-a-Fiat-la-yo-could” [click here to hear audio of some guy saying it properly].) These are examples of what geologists would refer to as an “explosive eruption”. Not all volcanoes blow ash into the atmosphere. Think of Kilauea in Hawaii – this is an example of an “effusive eruption” where lava oozes or bubbles up out of the ground in a rather non-violent manner. These are the most common volcanic eruptions on land that everyone should already be familiar with.

But, what happens when the volcano is underwater? You get what a group of New Zealand geologists are calling “Tangaroan” (named after the Maori god of the sea, Tangaroa). This article explains it in more detail, but the short version is this: at the bottom of the ocean, there is immense pressure from the weight of the water above the volcano that prevents an eruption from being truly “explosive”, yet the eruptions are often more violent than an effusive eruption. The magma, filled with gas, erupts into the ocean where the outer edges are instantly cooled and solidified. (The water is cold at the bottom of the ocean.) This traps all the gas inside and you get a rock that’s filled with millions of tiny air bubbles, which is called pumice. This new rock can be so light, it floats to the surface.

What does this have to do with VIIRS or a blog about imagery from weather satellites? Large underwater volcanic eruptions can create large quantities of pumice that float to the surface of the ocean and create what are called pumice rafts. VIIRS has seen these pumice rafts.

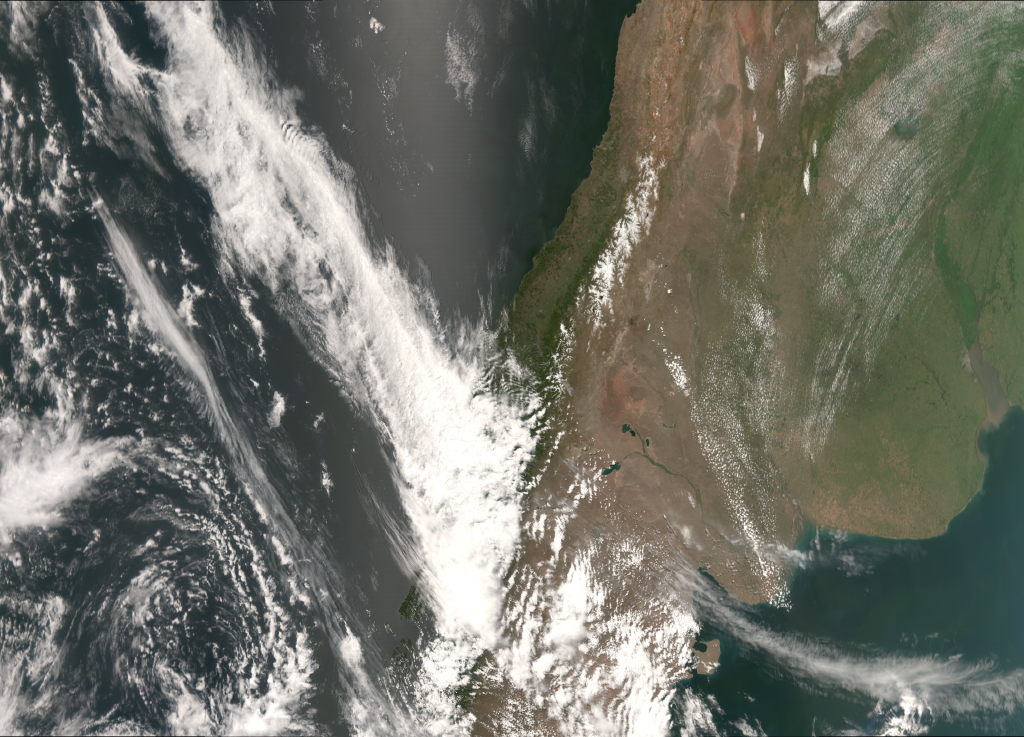

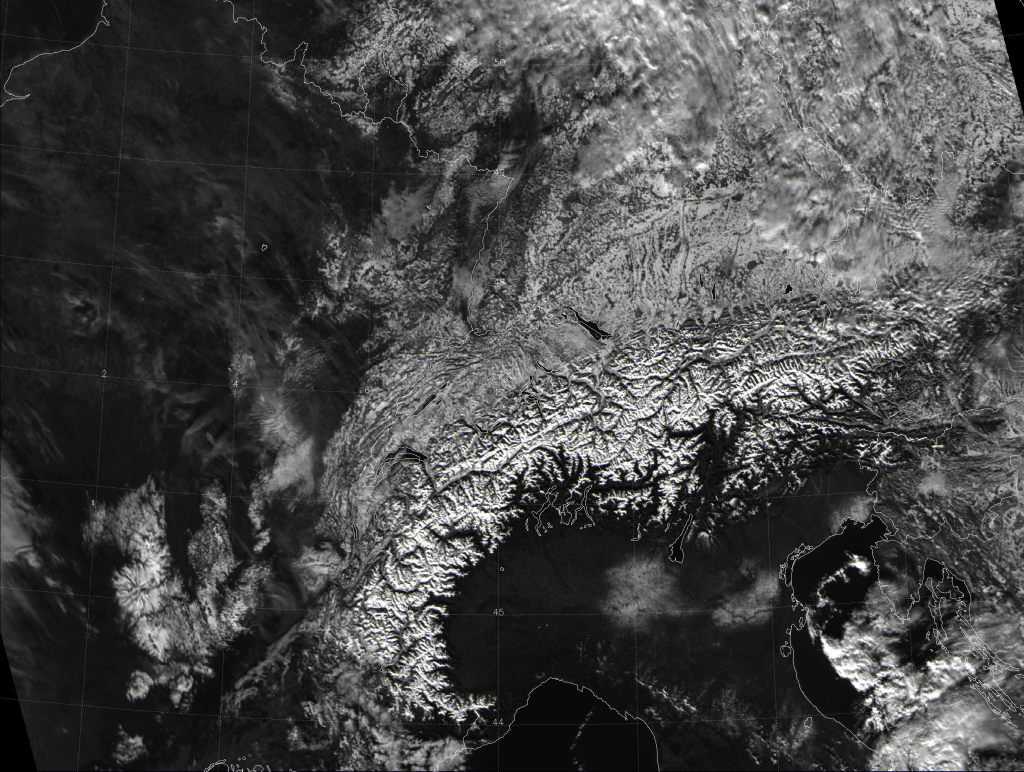

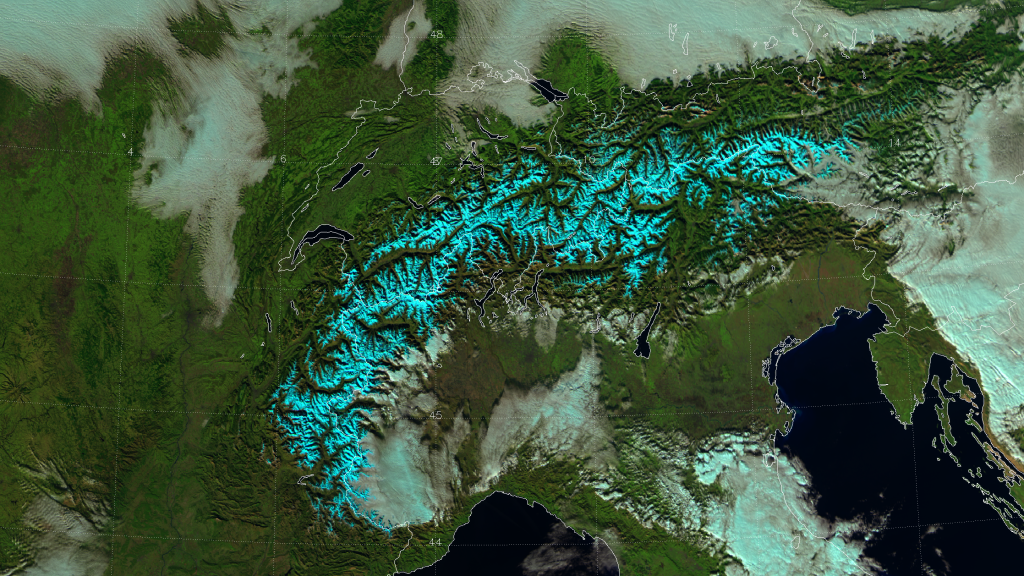

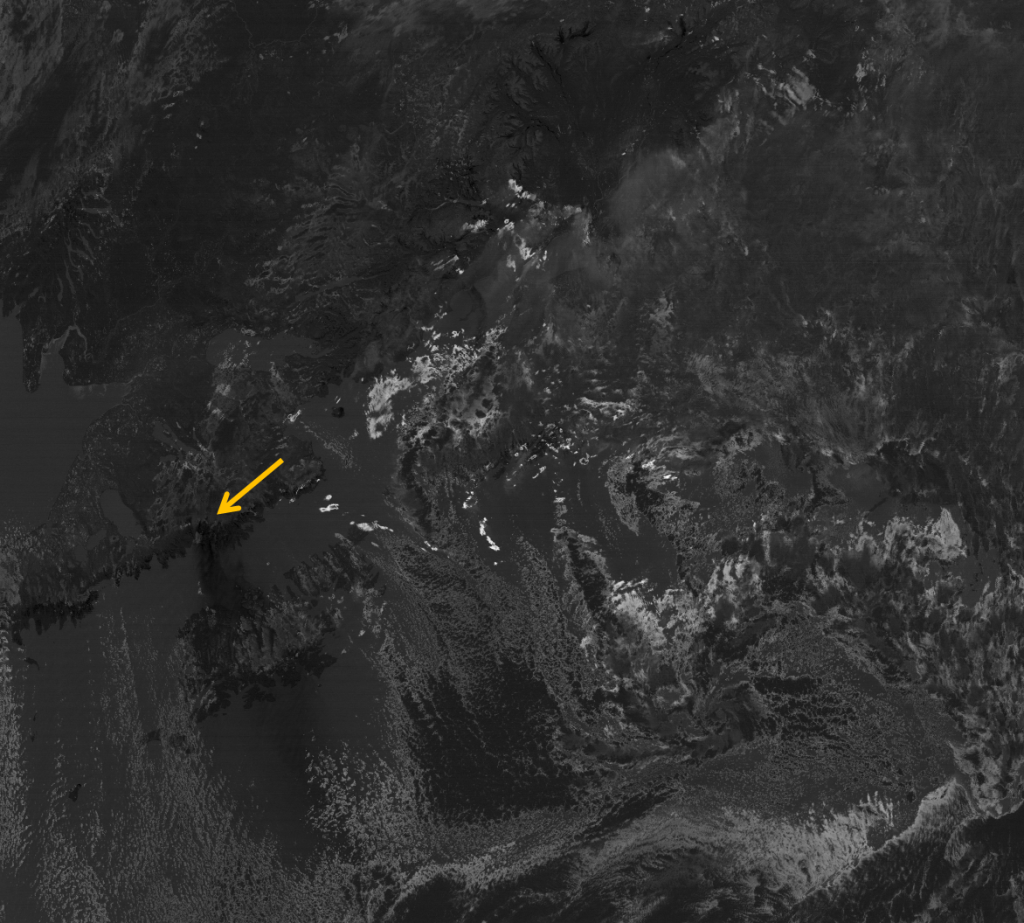

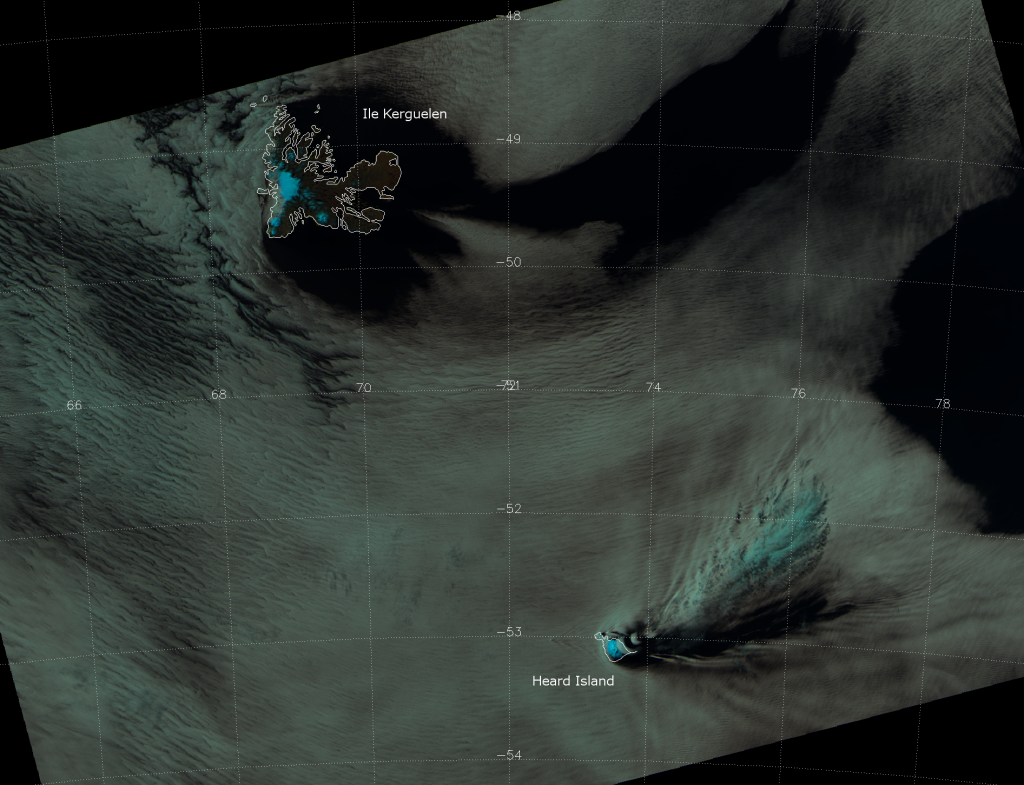

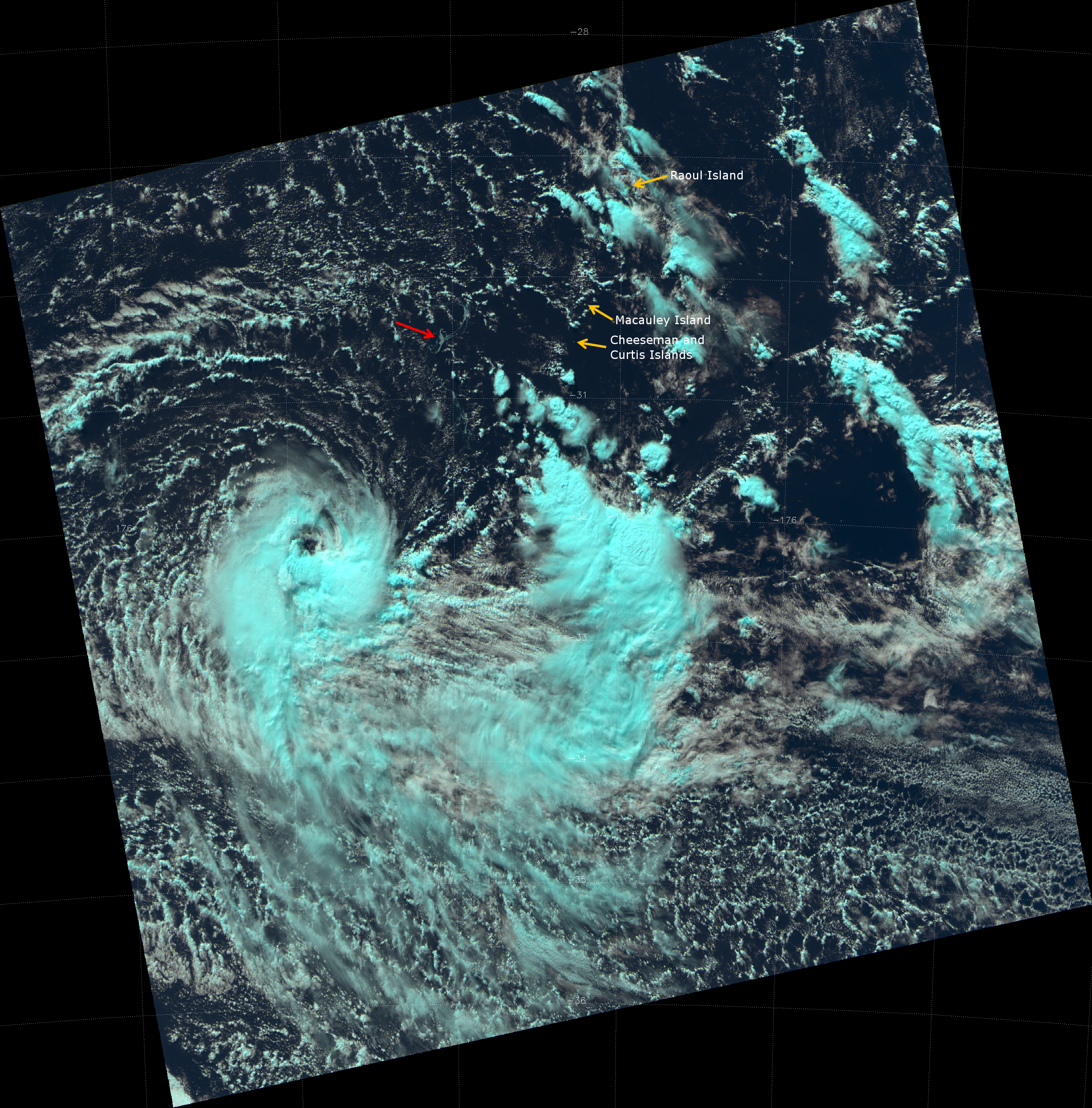

Here is a “natural color” or “pseudo-true color” RGB composite of VIIRS channels I-01 (0.64 µm, blue), I-02 (0.865 µm, green) and I-03 (1.61 µm, red), taken at 01:40 UTC 27 August 2012. Notice anything unusual in the water?

As always, click on the image, then on the “2798×2840” link below the banner to see the full resolution image. All those pale blue-gray swirls in the ocean surrounding Raoul Island and Macauley Island are the pumice rafts. They almost look like someone sprayed “Silly String” in the ocean.

To get a sense of the scale of these rafts, the latitude lines plotted on the image are ~111 km apart. Some of these rafts are 1-2 km wide in places. In this image you can see pumice rafts stretching from about 27.5 °S to 31.5 °S latitude and from about 175 °W to 178 °E longitude. That is a lot of floating rocks!

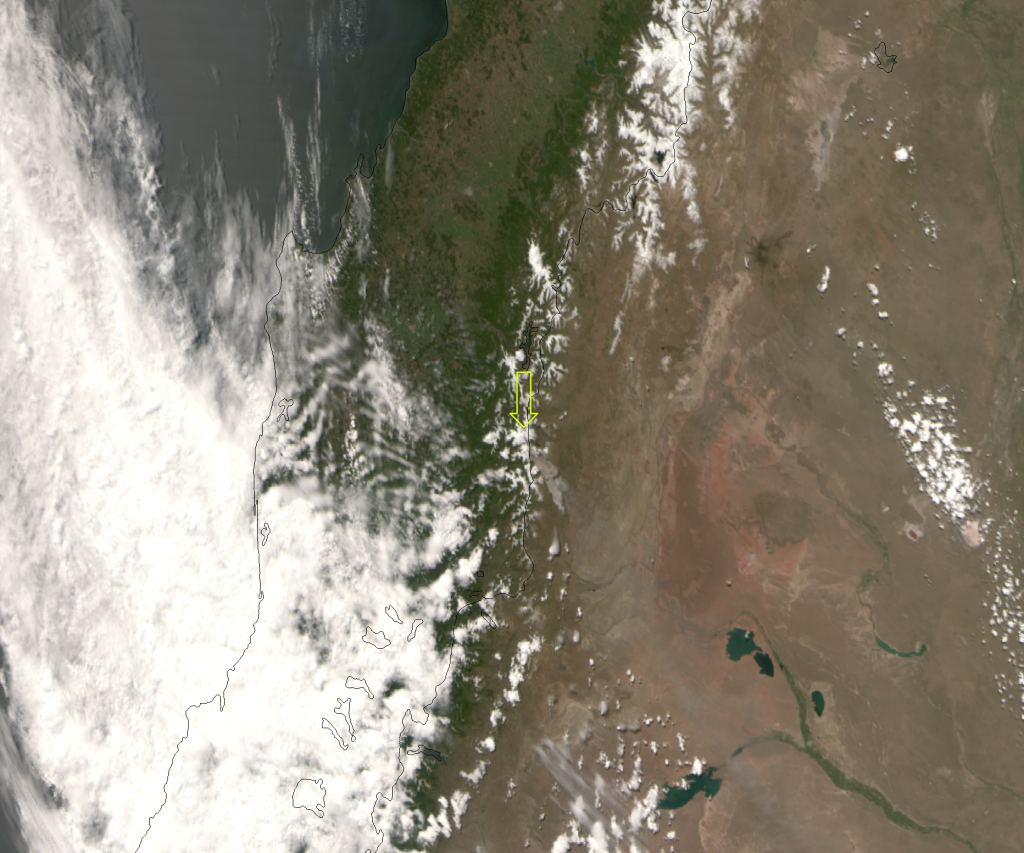

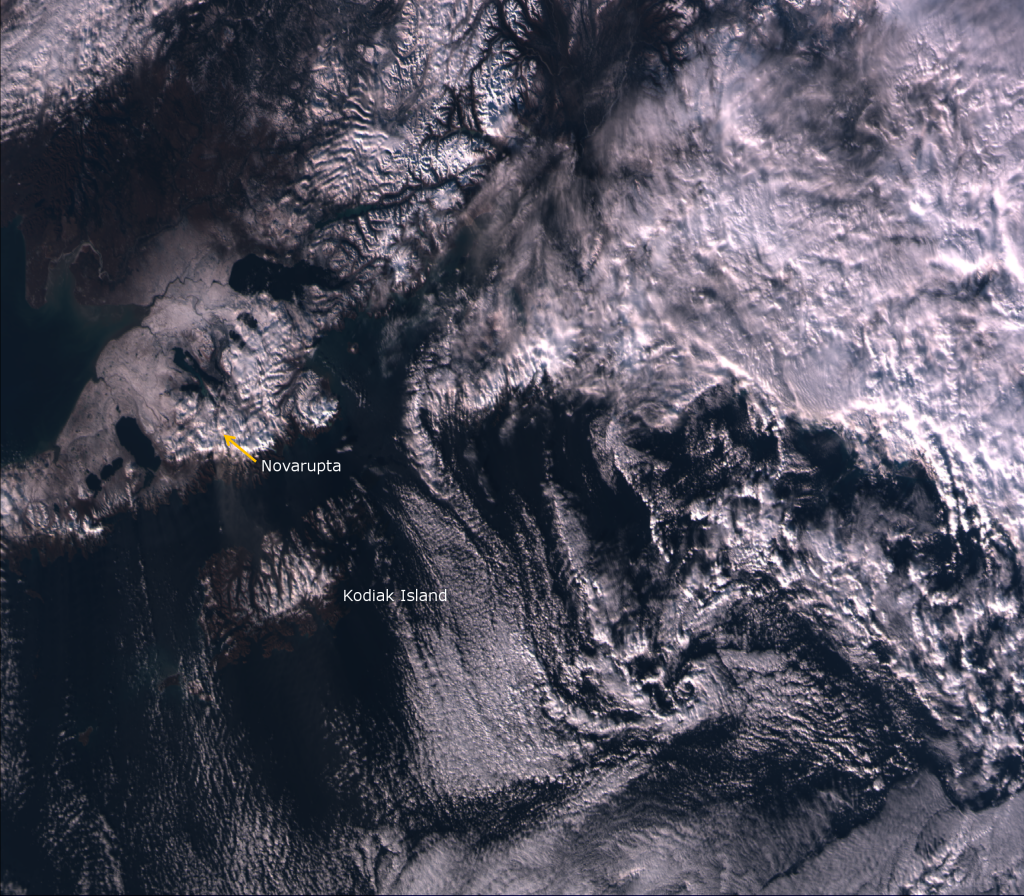

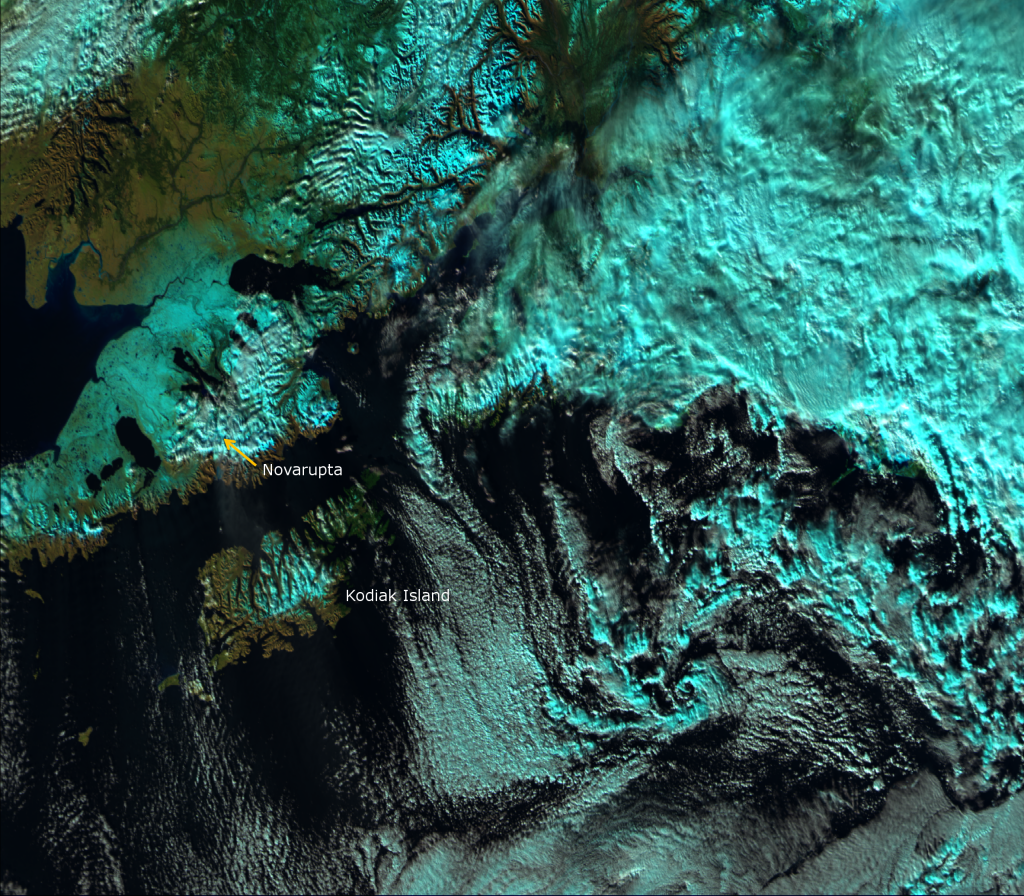

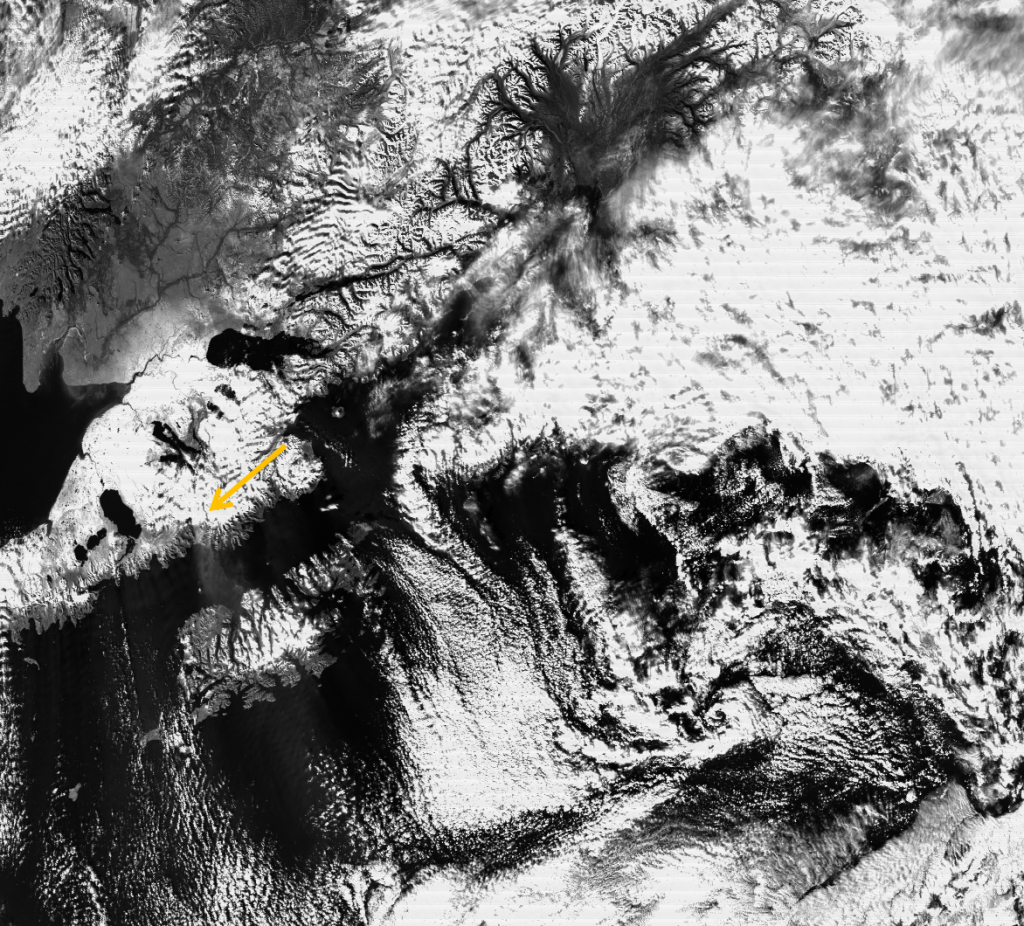

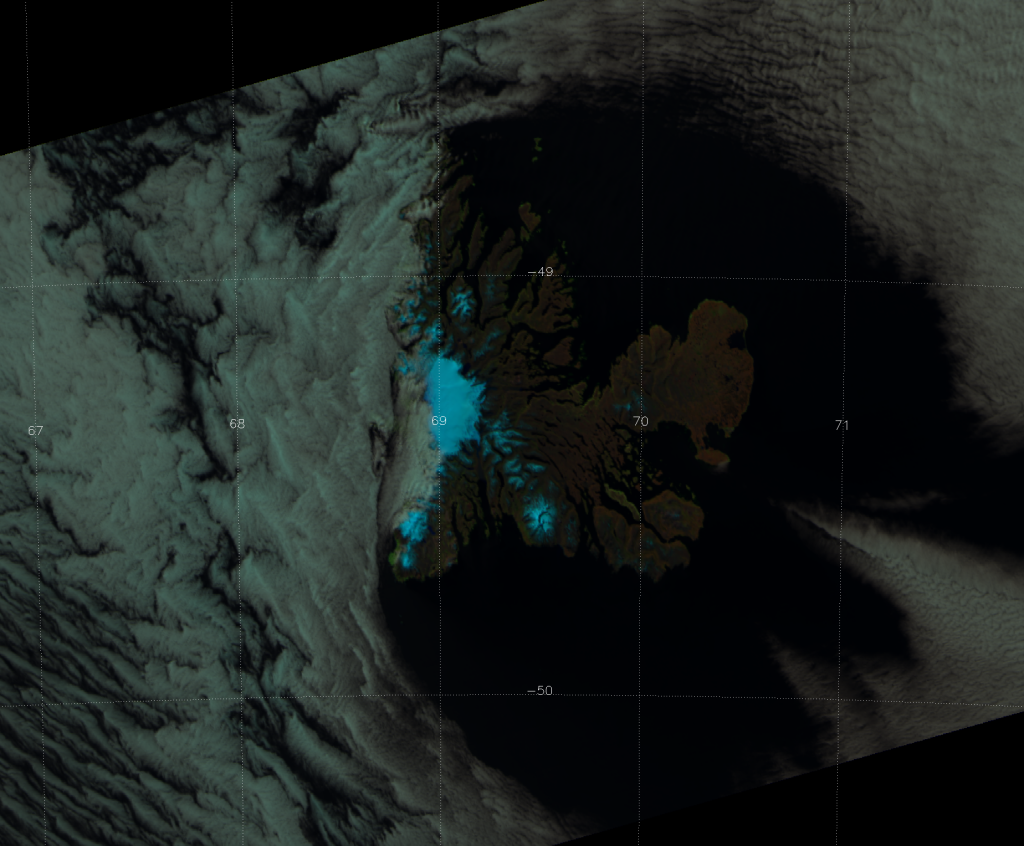

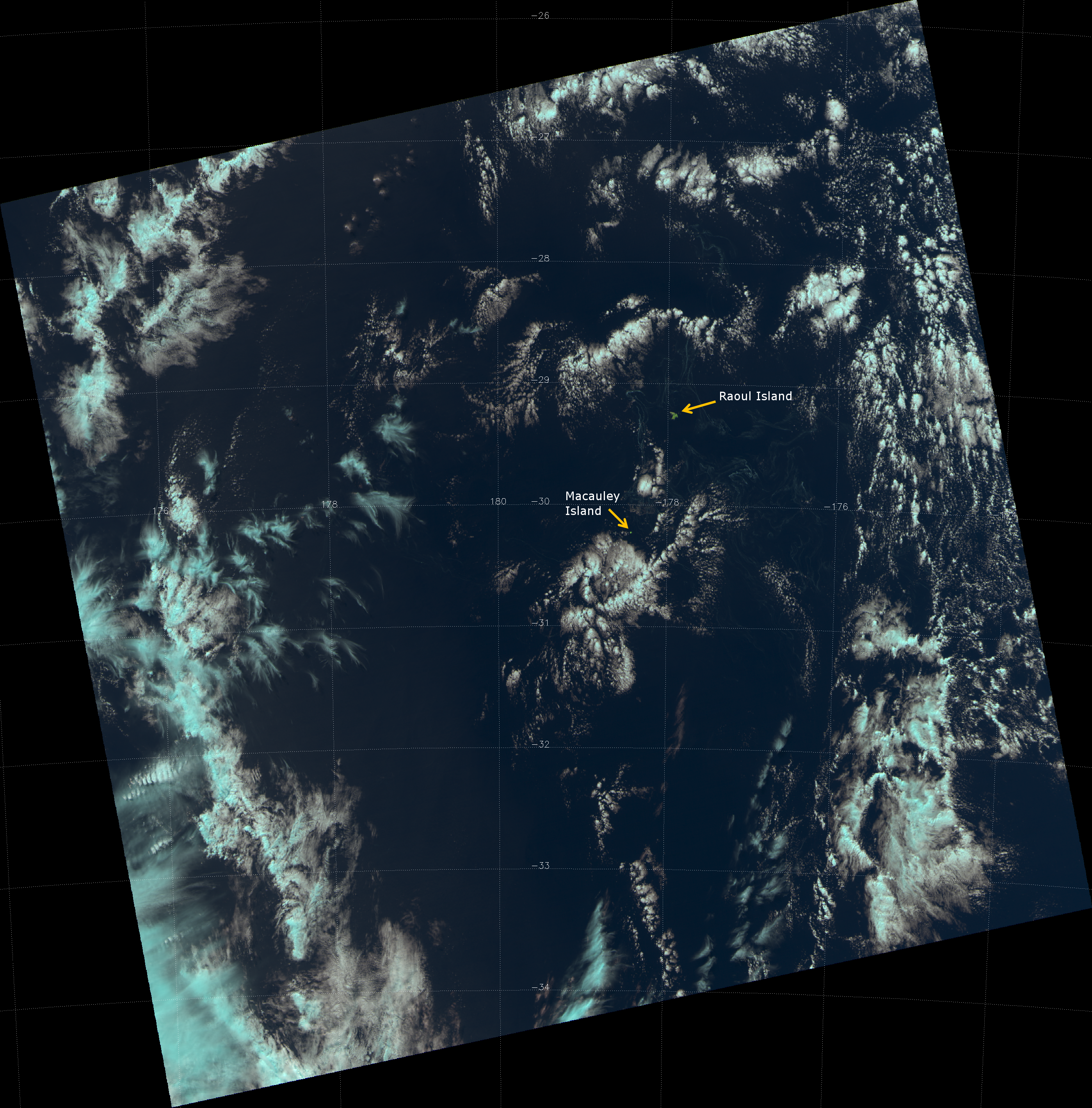

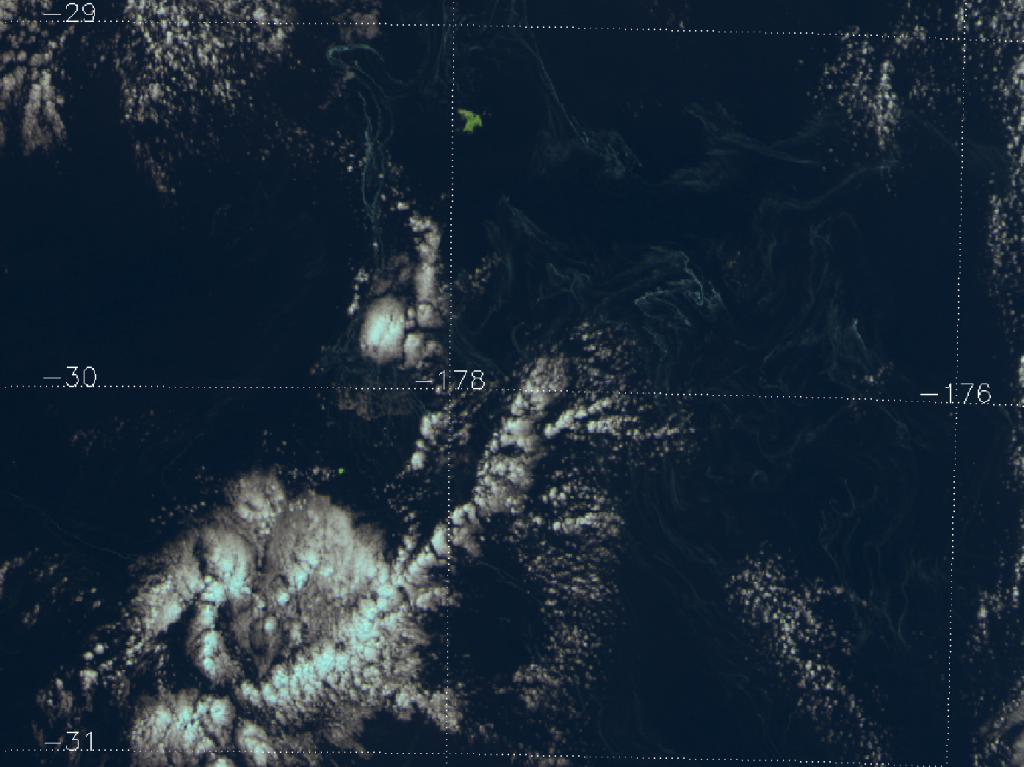

Here is a zoomed version of the previous image:

The main concentration of floating pumice is in the box the covers the area from 29 °S to 30 °S latitude and from about 176 °W to 178 °E longitude, although there is plenty of pumice south of that box – it’s just a little harder to see.

As an aside, Raoul and Macauley islands are part of the Kermadec Islands of New Zealand. If you’re interested, the New Zealand government is always looking for volunteers to spend six months on Raoul Island pulling weeds and keeping invasive species off the island. (There, that saves me from doing a Remote Island post to cover this.)

These pumice rafts have been traced back to the eruption of the Havre Seamount (an underwater volcano) on 18 July 2012. This new eruption is part of the “Ring of Fire” in the southwestern part of the Pacific Ocean, roughly 1,000 kilometers northeast of New Zealand. If you believe the Wikipedia article linked to first in this paragraph, the eruption was unknown until an aircraft passenger took pictures of the pumice raft from her plane on 31 July 2012. I have been able to track this pumice back to 26 July 2012. Before that, it is too cloudy, making it difficult to see anything. (Apparently, MODIS saw it on 19 July 2012.)

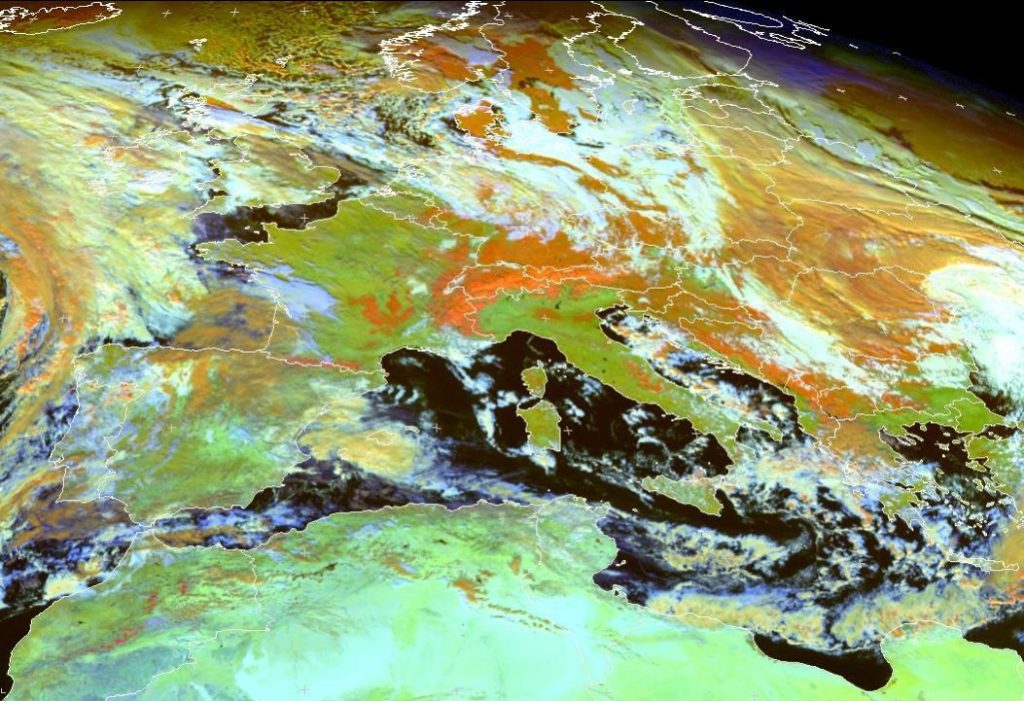

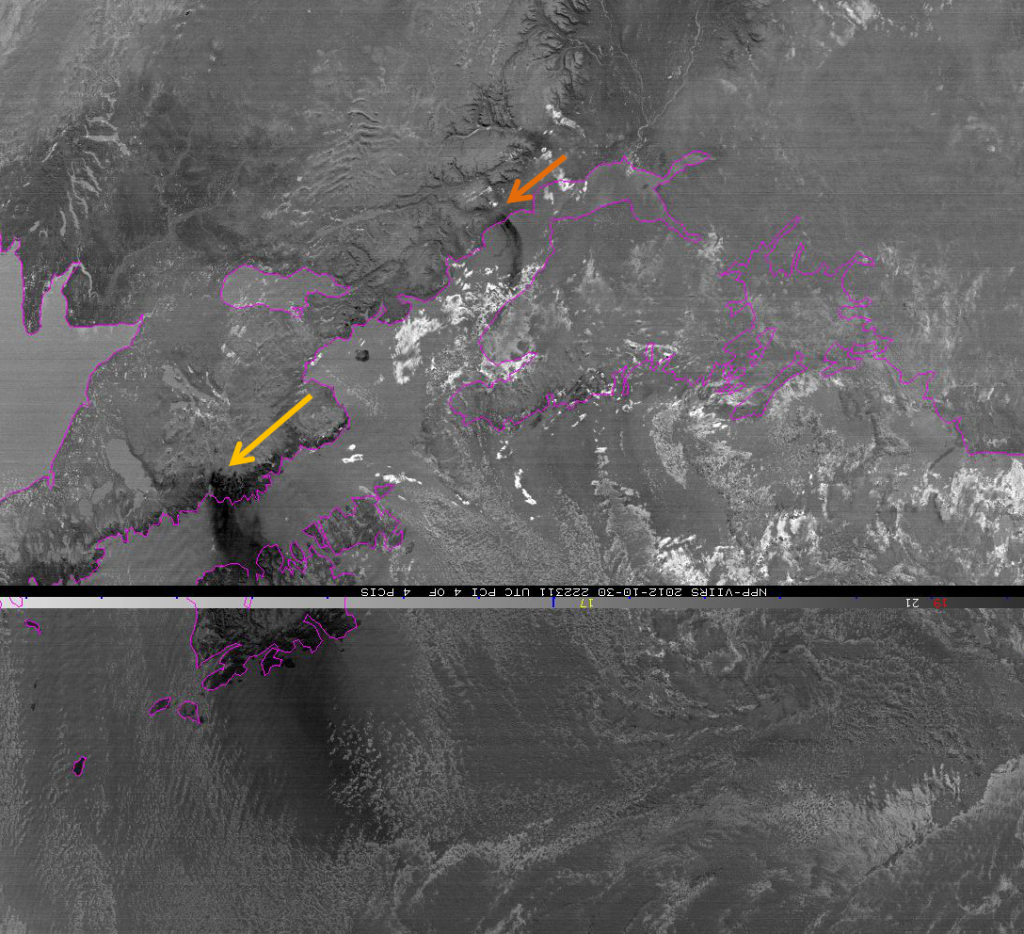

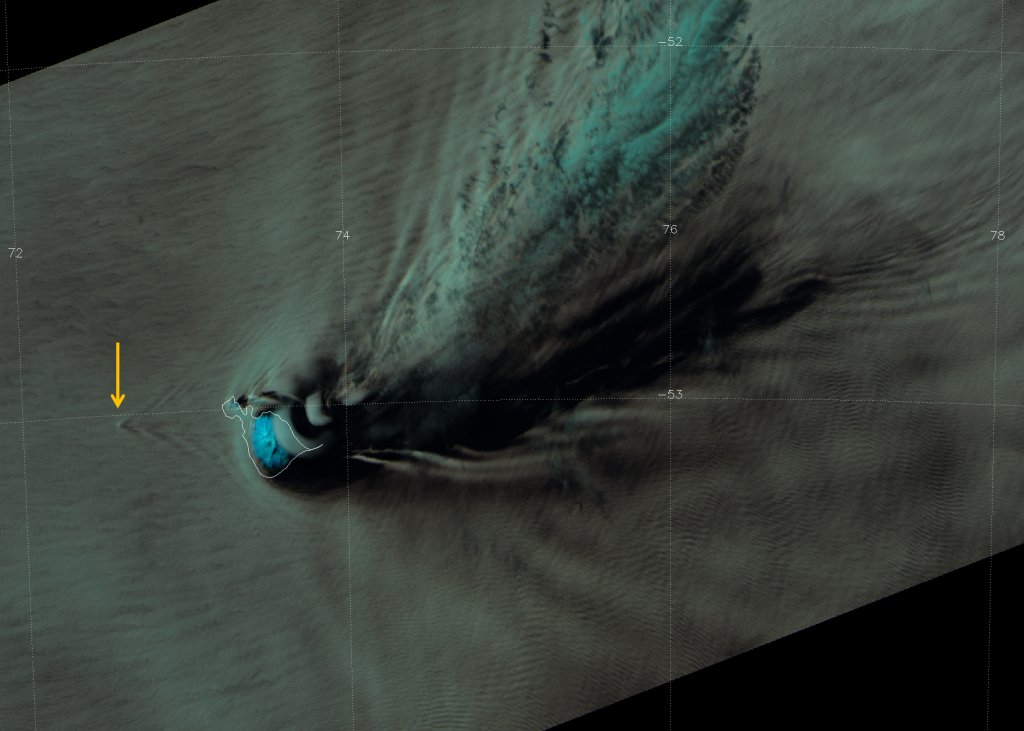

The red arrow points to the pumice raft. There’s a nice looking cyclone southwest of the pumice, but I’m not sure if it was given a name. If you zoom in, you can see Cheeseman Island and Curtis Island off to the east of the raft. These islands were obscured by clouds on the 27 August 2012 overpass. Cheeseman Island is only 7.6 ha (19 acres) and Curtis Island is 40 ha (99 acres), yet VIIRS has the resolution to see them!

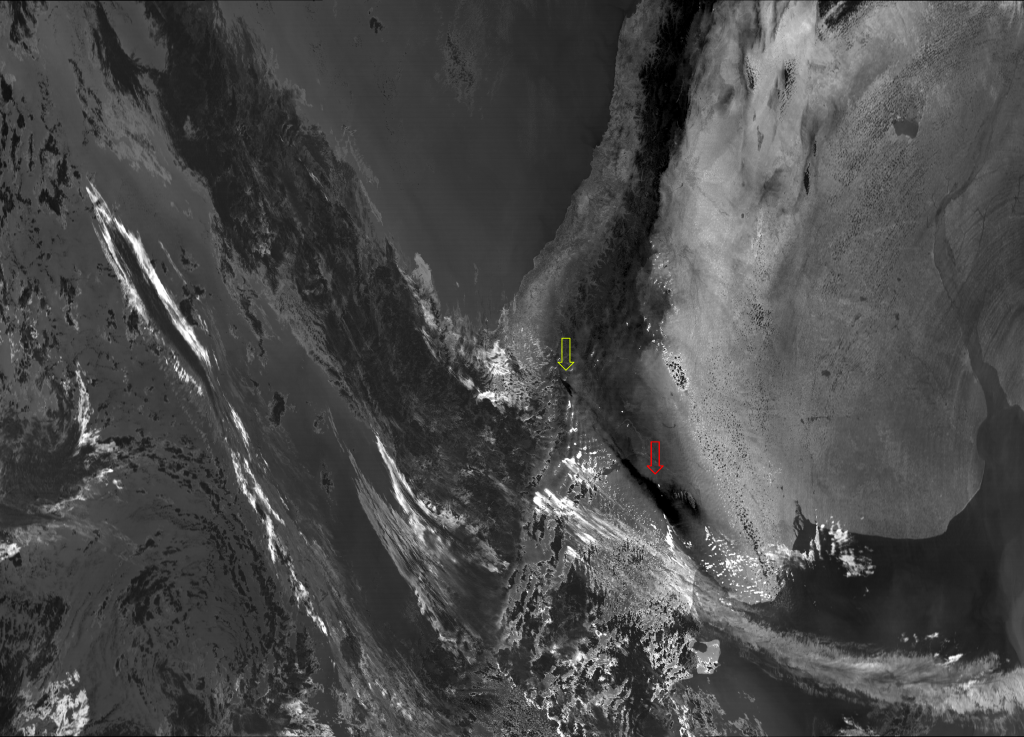

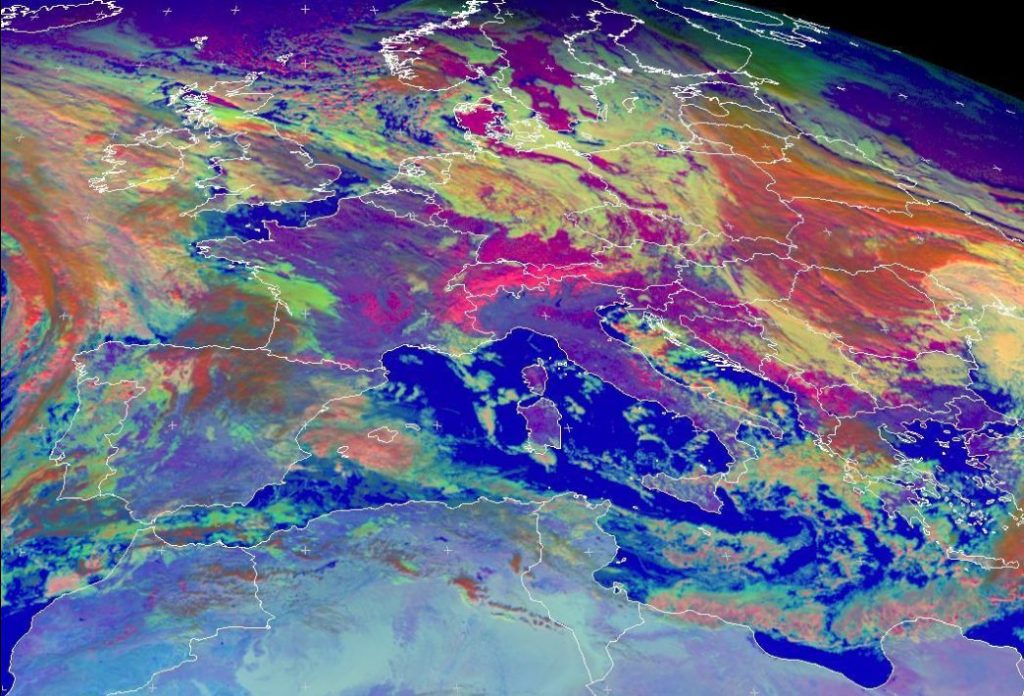

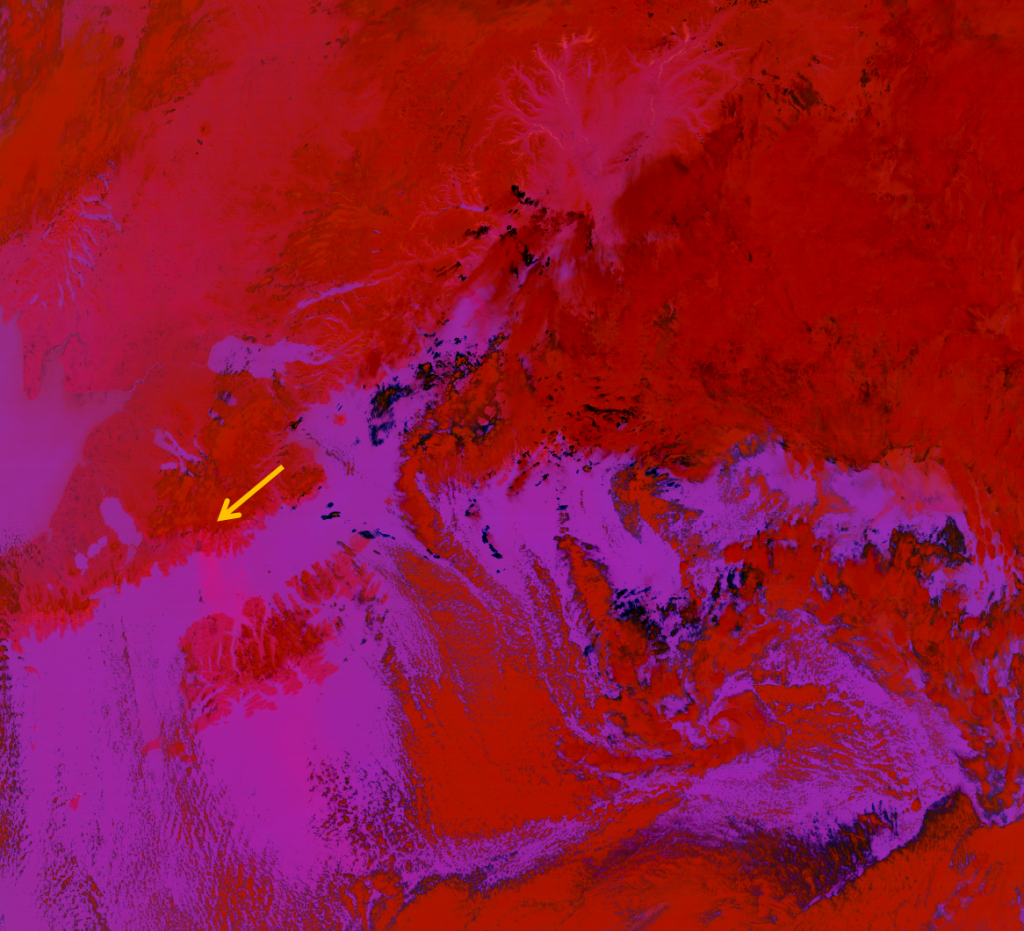

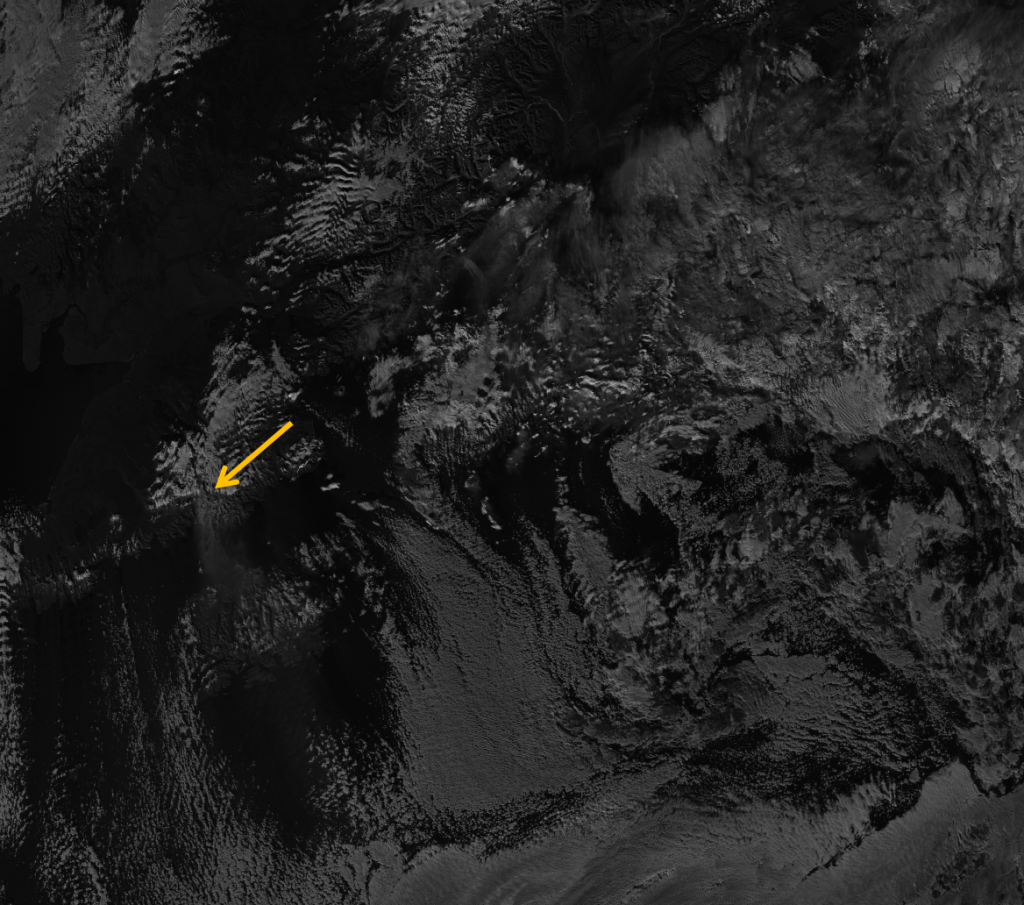

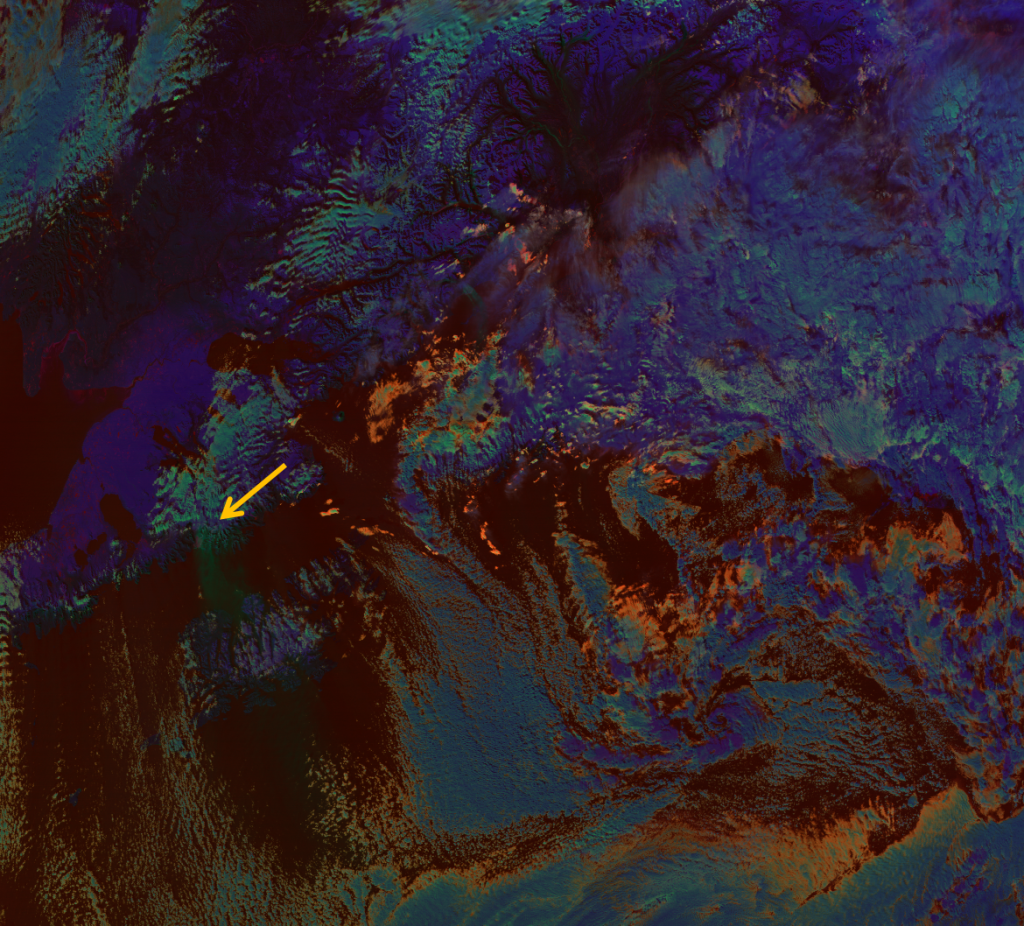

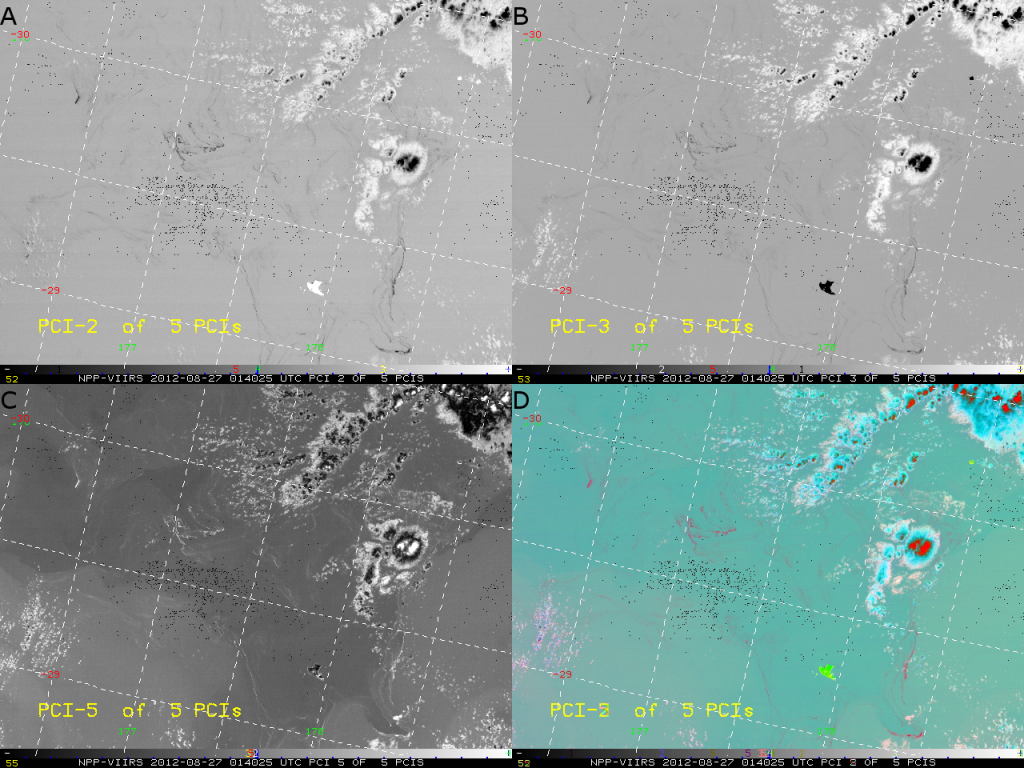

In an effort to highlight these pumice rafts, a PCI analysis was performed on the five VIIRS high-resolution imagery (I-band) channels. PCI analysis uses principal components to identify the major modes of variability within the data. Analysis of the 5 VIIRS I-bands resulted in 5 PCIs or component images. Of those components, PCI-2, 3, and 5 appeared to show the pumice rafts. A particular RGB combination of those three components (red = PCI-5, green = PCI-2 and blue = PCI-3) resulted in the pumice appearing red on a green-blue ocean. Clouds are white, then cyan and then red for colder cloud-top temperatures. (Certain pepper-like black pixels are out of range in the PCI analysis.) The three principal components that highlight the pumice rafts are shown in the figure below, along with the resulting RGB composite. Unfortunately, these images were made using McIDAS-X, which has a habit of plotting VIIRS data upside-down. Therefore, north in each image is at the bottom.

This in an image you’ll want to zoom in on to see the details as you consider the information in the previous paragraph. There are two main results of this PCI analysis: it can be used to highlight pumice rafts (although they have the same color as cold cloud tops) and the temperature information from channel I-5 (11.5 µm), which shows up in PCI-5, indicates that the pumice has a tendency to collect along gradients in sea surface temperature.

Being able to track the pumice rafts is important for geology, biology and oceanography. They can act as a tracer for following ocean currents. Some of them crack and fill with water, causing them to sink to the bottom, depositing the newly formed rock in other parts of the sea floor. The nature of the pumice gives clues about what happens in underwater volcanoes, a process that is not well known at this point. And, as these floating pieces of pumice are carried around, organisms like algae, coral, and barnacles will attach to them and grow, eventually settling in far away places. Studying these rafts may shed new light on how life can spread across the oceans.

So, yes – rocks can float. And they can be seen by a weather satellite with 375 m resolution.