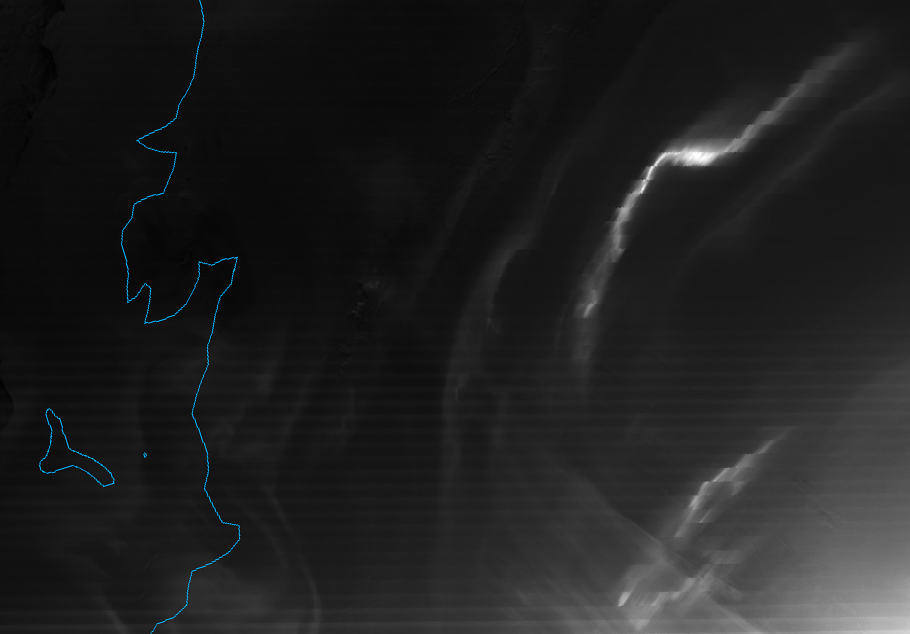

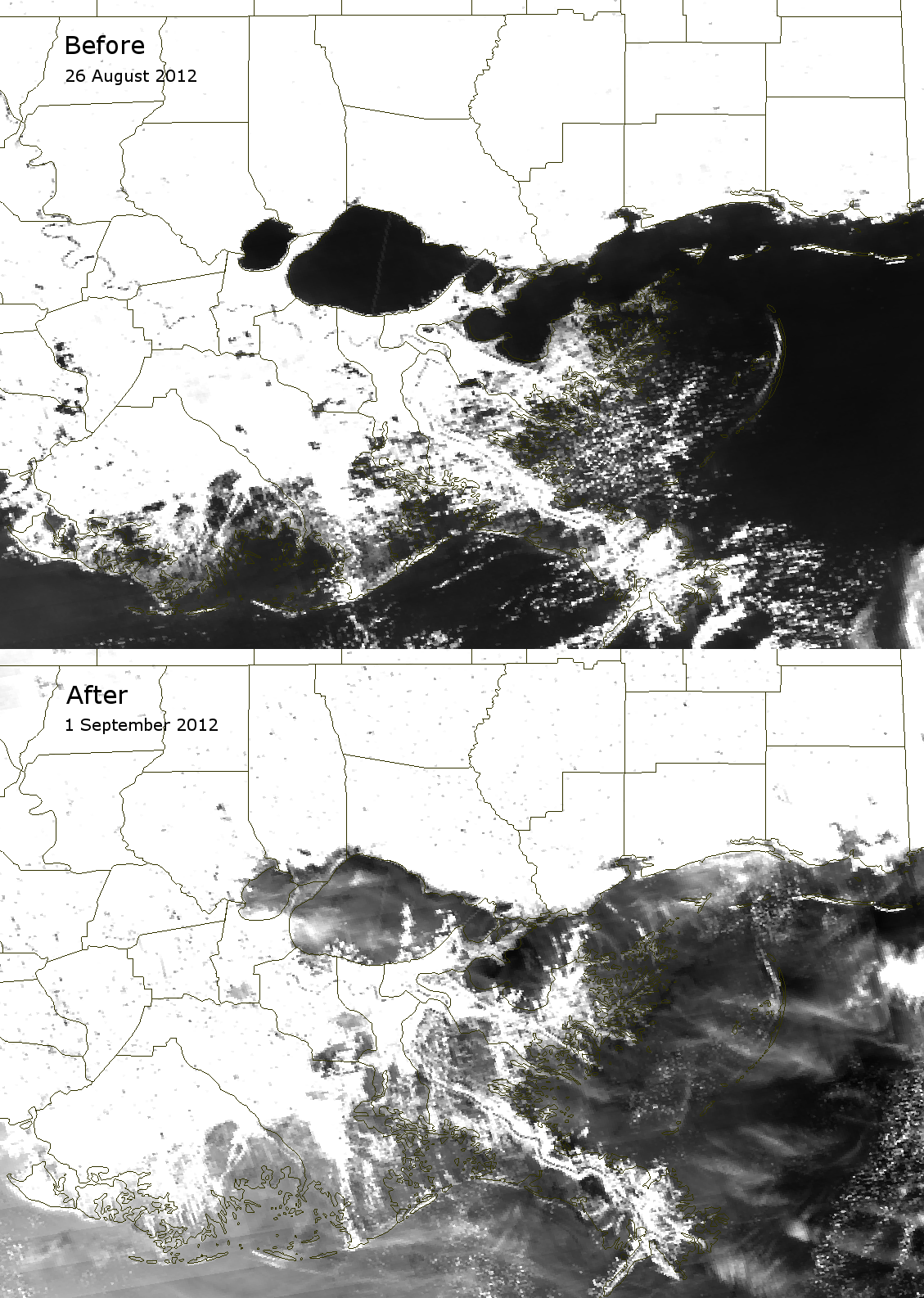

Last time we visited Greenland, it was because VIIRS saw evidence of the rapid ice melt event in July 2012. We return to Greenland because of this visible image VIIRS captured on 18 October 2012:

This image was taken by the high-resolution visible channel, I-01 (0.64 µm), and was cropped down to reduce the file size. Greenland is in the upper-left corner of the image. The northwest corner of Iceland is visible in the lower-left corner of the image.

So, what’s with all the swirls off the coast of Greenland? Are they clouds swirled around by winds? Or some kind of sea serpent – perhaps a leviathan or a kraken? (Based on the descriptions, they would be big enough for VIIRS to see them.)

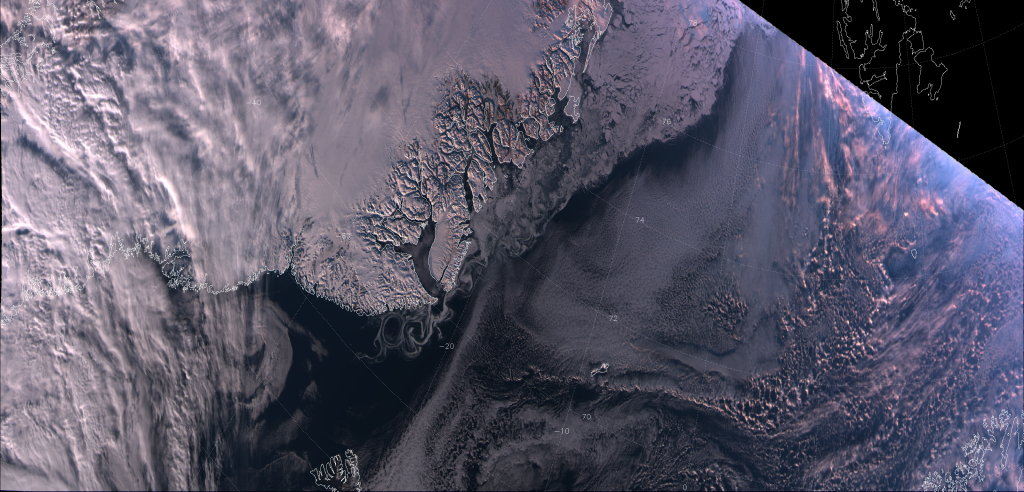

Sadly, for all you science fiction and fantasy fanatics, those swirls are just icebergs breaking up as they enter warmer water, the chunks of ice caught up in eddies in the East Greenland Current. This is easier to see when you look at the “true color” image below:

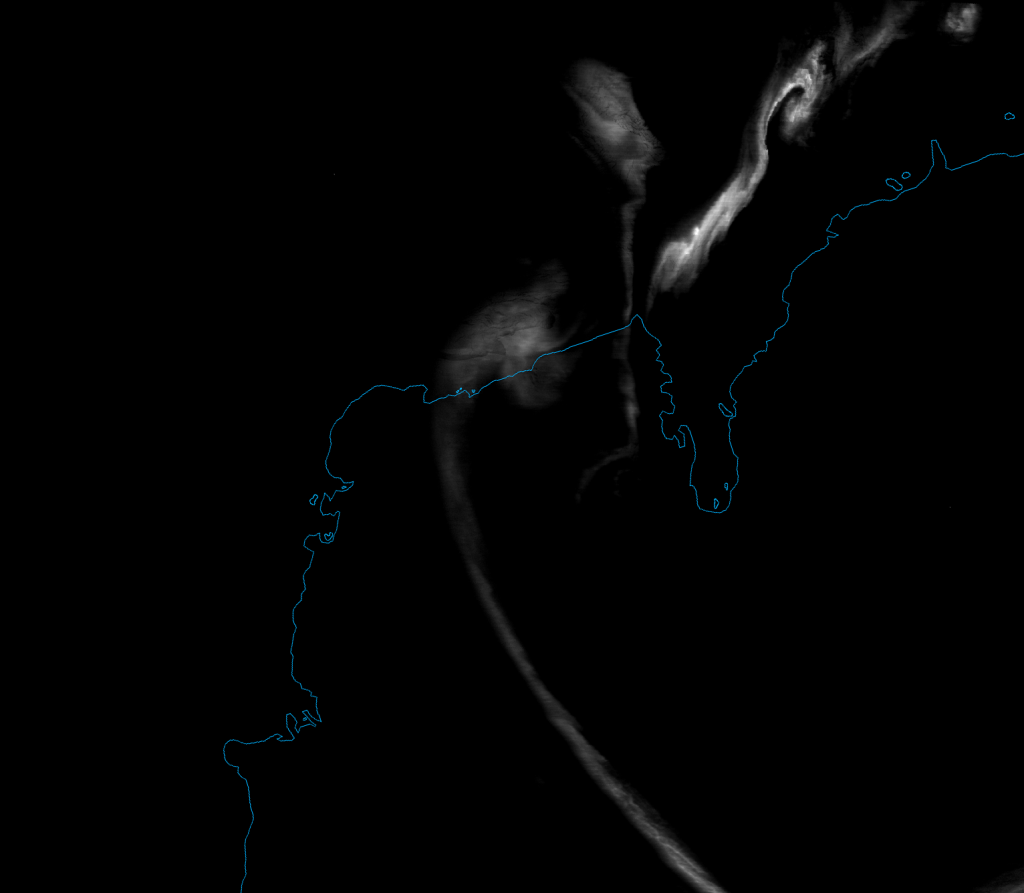

Make sure to click on the image, then on the “3200×1536” link below the banner to see the image at full resolution. Since the true color RGB composite is made from moderate resolution channels M-03 (0.488 µm, blue), M-04 (0.555 µm, green) and M-05 (0.672 µm, red), we can include more of the swath before we get into file size issues. That allows us to see the extent of the ice break-up along the Greenland coast.

There is a lot to notice in the true color image. The large icebergs at the top of the image breakup into smaller and smaller icebergs as they float down the east coast of Greenland, until they finally melt. These visible “swirls” (or “eddies” in oceanography terms) extend from 75 °N latitude down to 68 °N latitude where the ice disappears (melts).

The upper-right corner with missing data is on the night side of the “terminator” (the line separating night from day), where we lose the amount of visible radiation needed for these channels to detect stuff. (The Day/Night Band would still collect data, however, as it is much more sensitive to the low levels of visible radiation observed at night.) See how the ice and the high clouds appear to get a bit more pink as you move from west (left) to east (right)? It’s the same reason cirrus clouds often look pink at sunset. The sun is setting on the North Atlantic and more of the blue radiation from the sun is scattered by the atmosphere than red radiation. The red radiation that’s left is then reflected off the clouds (and ice and snow) toward the satellite.

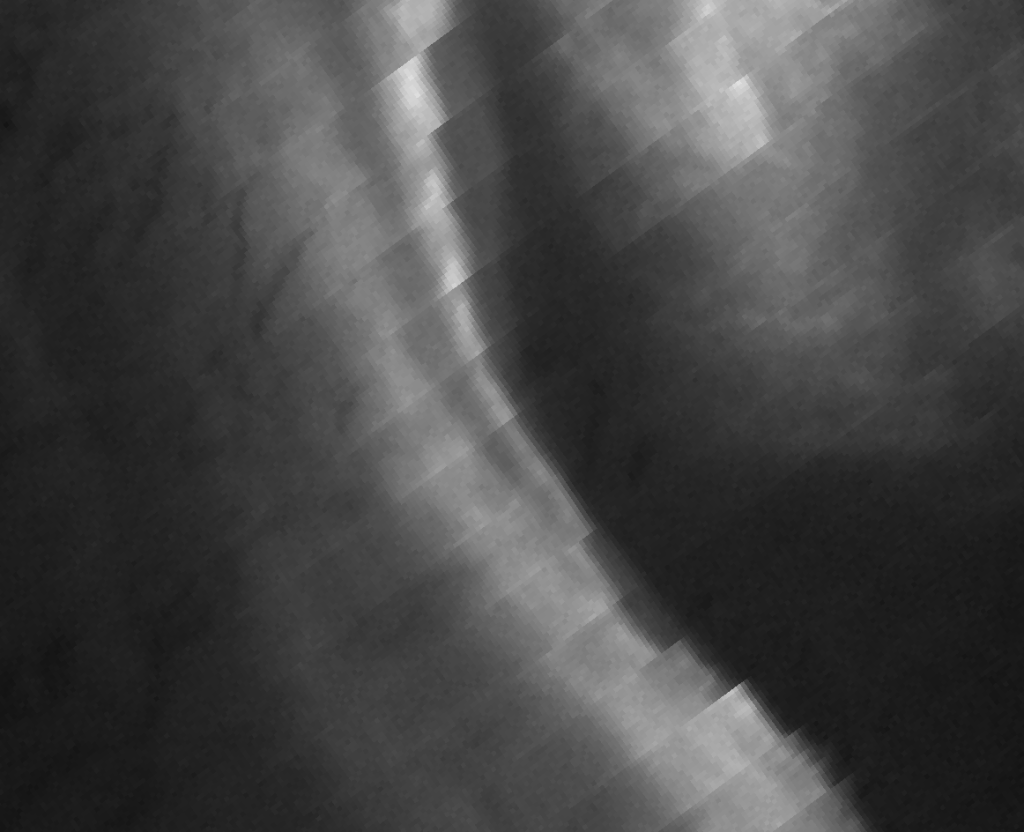

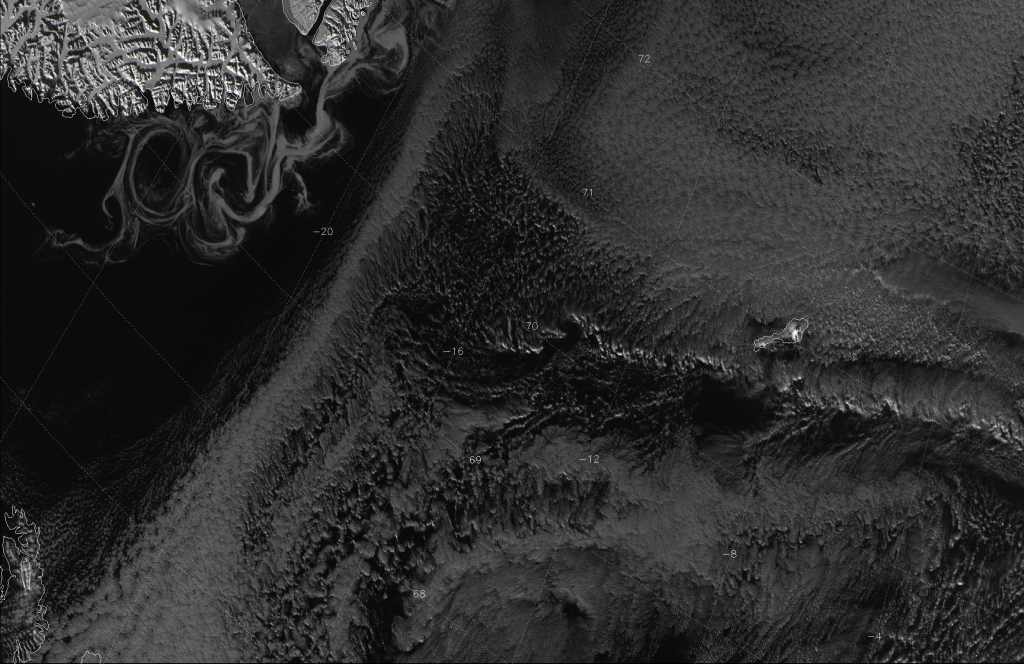

Just to prove that the swirls are indeed ice and not clouds, here’s the “pseudo-true color” (a.k.a. “natural color”) RGB composite made from channels M-05 (0.672 µm, blue), M-07 (0.865 µm, green) and M-10 (1.61 µm, red):

The deep blue color of the swirls in this RGB composite is indicative of ice, not clouds. These channels are not impacted by atmospheric scattering at any sun angle, though, so there is no change in the color of the clouds as you approach the terminator.

You may have also noticed the cloud streets downwind of the icebergs off the coast of Greenland. These clouds are formed in the same way as lake-effect clouds are in the Great Lakes. Cold, arctic air flowing south over the icebergs meets the relatively warm water of the open ocean. The moisture evaporating from the warmer waters condenses in the cold air and forms clouds.

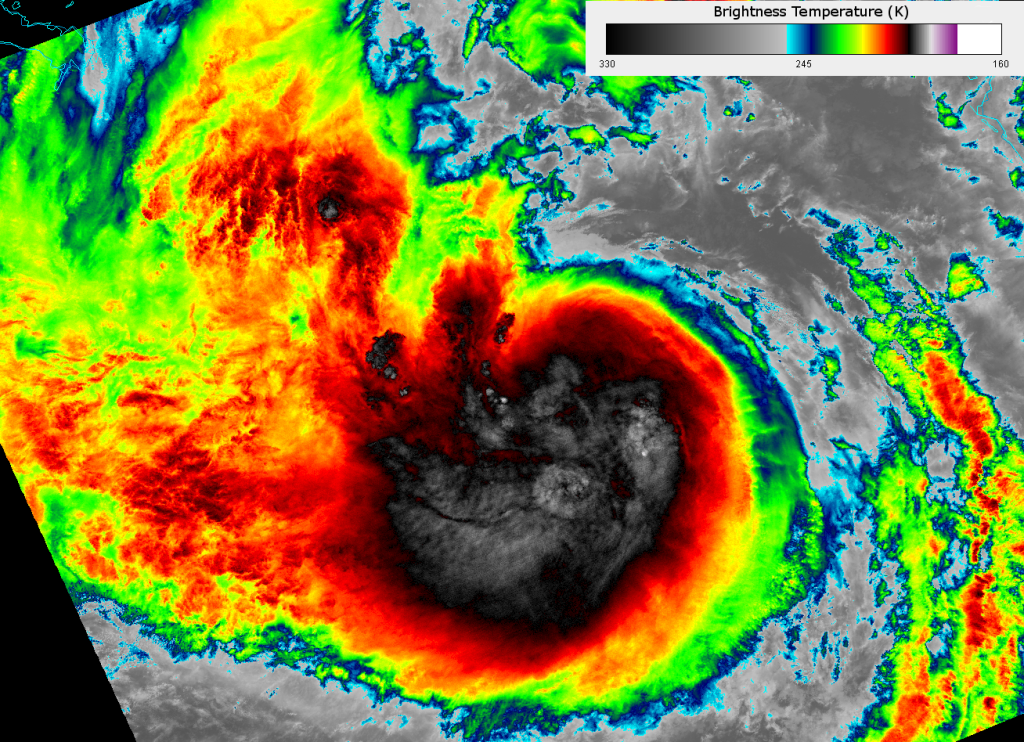

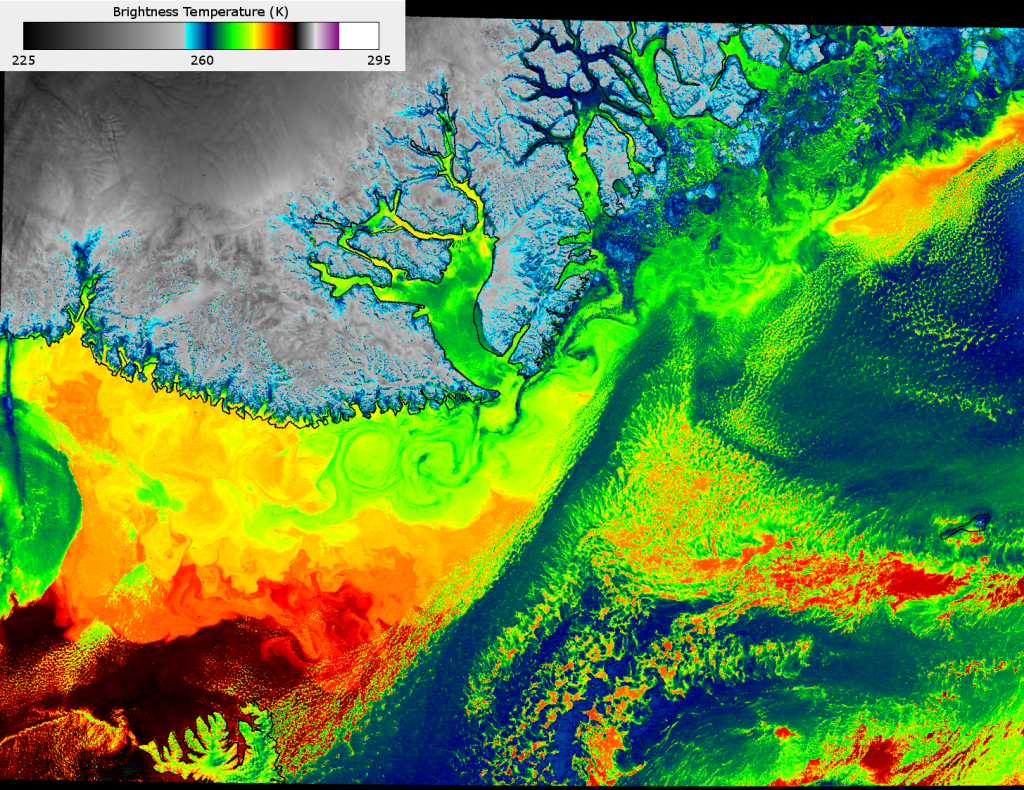

How much warmer is that water? Here’s the high-resolution infrared (IR) image (I-05, 11.45 µm):

At ~375 m resolution at nadir, this is the highest resolution available in the IR on a non-classified satellite today. Look at all the structure in the cloud-free areas of the ocean! Lots of little eddies show up in the IR that are invisible in the visible and near-IR channels shown previously. The only eddies visible in the true color and natural color images are the ones that had ice floating in them. Here we see they extend much further south than the ice.

The ice-free water that is not obscured by clouds is 10-15 K warmer than where the icebergs are found. The eddies are caused by the clash between the southward flowing, cold Eastern Greenland Current and the northbound, warm North Atlantic Drift (the tail end of the Gulf Stream), which are important in the global transport of energy. They are not ship-sinking whirlpools caused by any krakens in the area – at least VIIRS didn’t observe any.

UPDATE (February 2013): Below is another image of the eddies and swirls off the eastern coast of Greenland. This “natural color” image was taken 13:34 UTC 15 February 2013:

Since it is winter, the ice extends further south along the coast before it melts. Once again, there is a lot of structure visible in the edge of the ice, where the East Greenland Current and North Atlantic Drift interact. Another thing to notice is the shadows. At the top of the image just right of center is Scoresby Sound, which is completely frozen over. Given that the sun is pretty low in the sky over Greenland in the winter (if it rises at all, since most of Greenland is north of the Arctic Circle), the mountains south of the Sound cast some pretty long shadows on the ice. It’s possible to use the length of the shadows with the solar zenith angle to estimate the height of those mountains (although there are more accurate ways to determine a mountain’s elevation from satellite). VIIRS provides impressive detail, even from the moderate resolution bands.