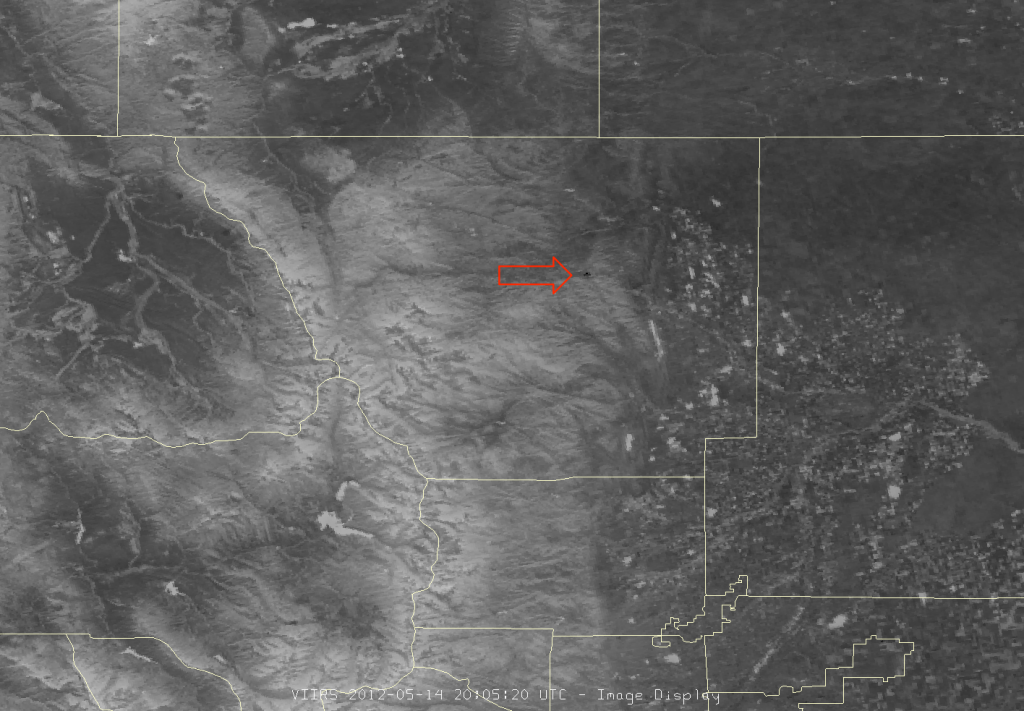

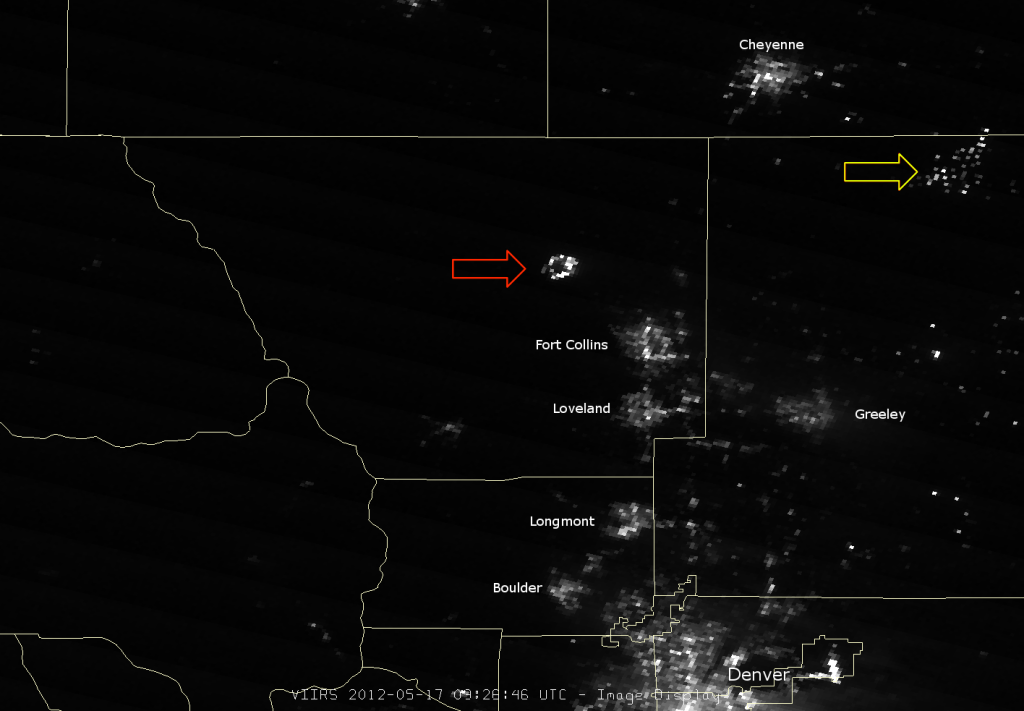

Last time on “Wild Week of Wildfires“, we looked at the Little Bear Fire and High Park Fire, two lightning-ignited fires burning out west that were so hot they caused saturation in the two 3.7 µm channels on VIIRS (I-04 and M-12). There was mention of the Duck Lake Fire, a lightning-ignited fire in northern Michigan, which VIIRS also saw, and I couldn’t resist showing some more images.

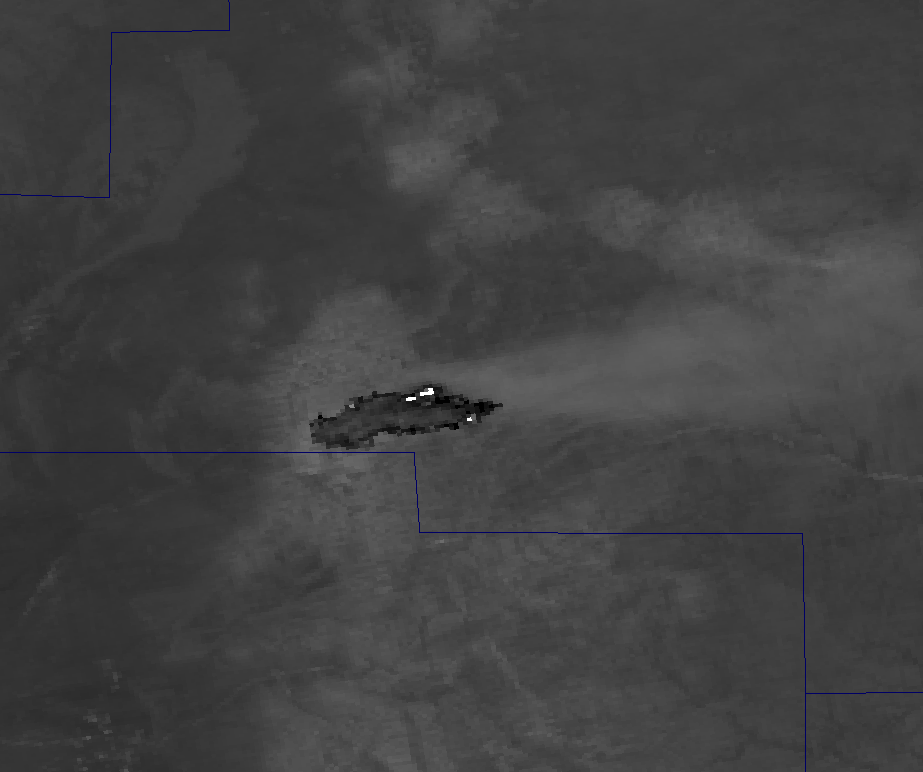

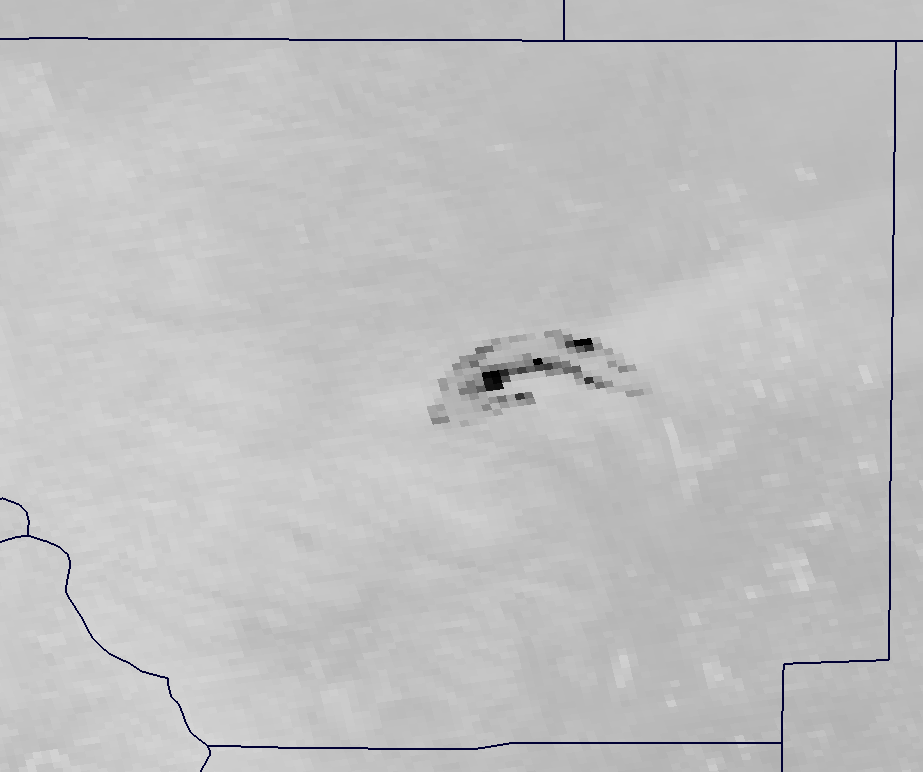

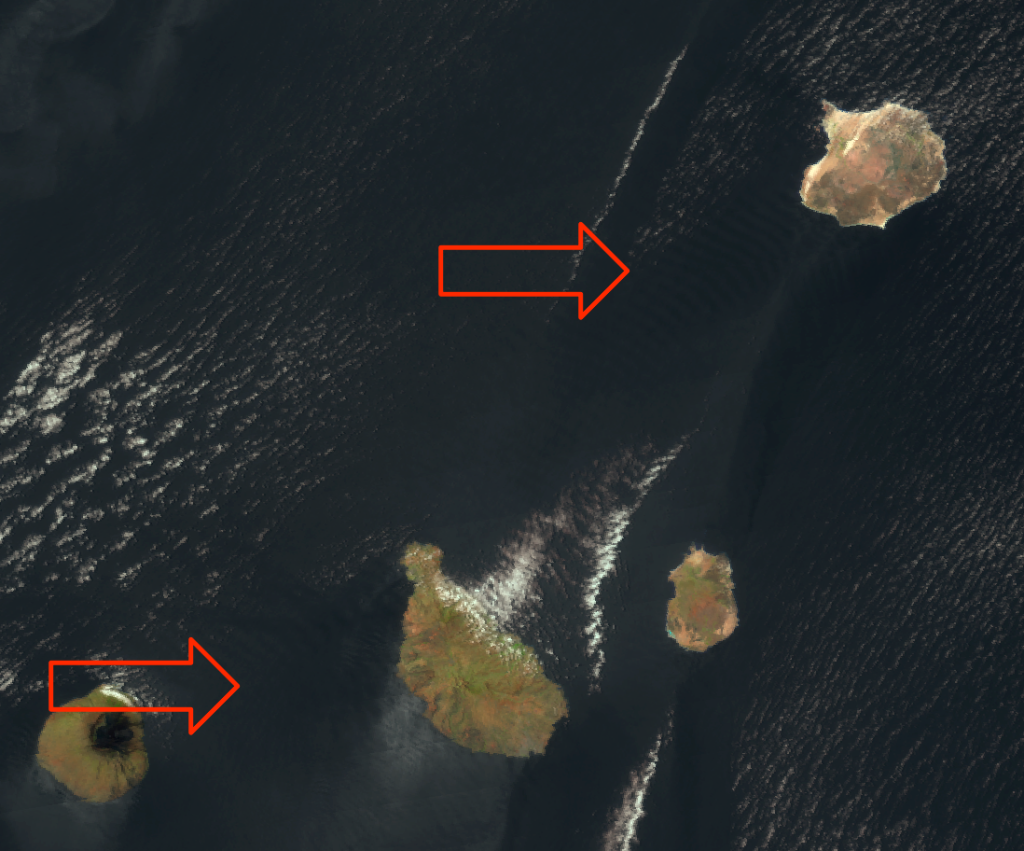

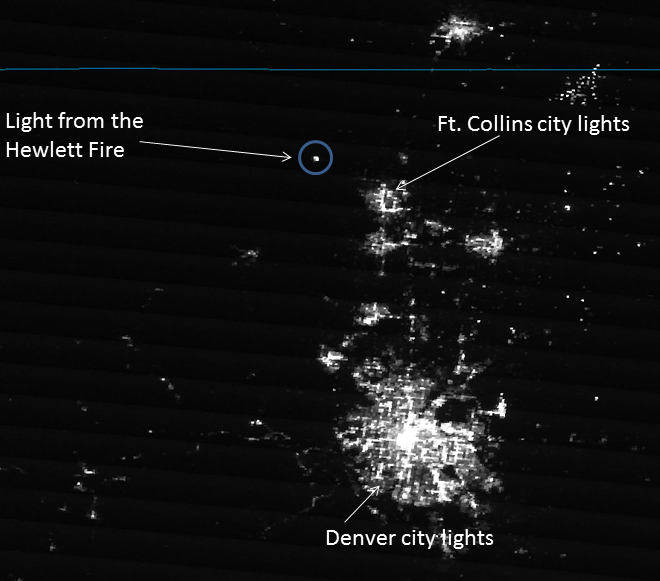

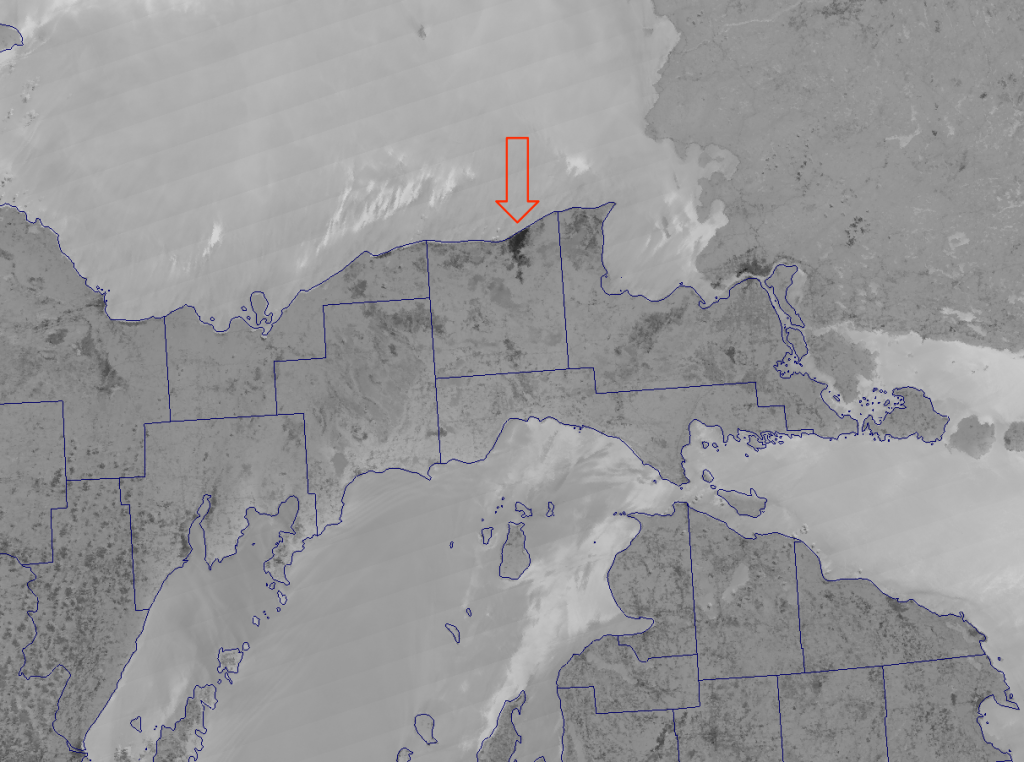

On 9 June 2012, the same day the High Park Fire exploded (figuratively speaking), the Duck Lake Fire finally reached 100% containment after burning over 21,000 acres. The next day (10 June 2012), Suomi NPP passed over the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and it was actually a clear day. (This joke comes courtesy of 20+ years experience of living in Michigan.) Even with 100% containment, the hot spot of the fire was still clearly visible in VIIRS channel I-04 (3.7 µm) that afternoon:

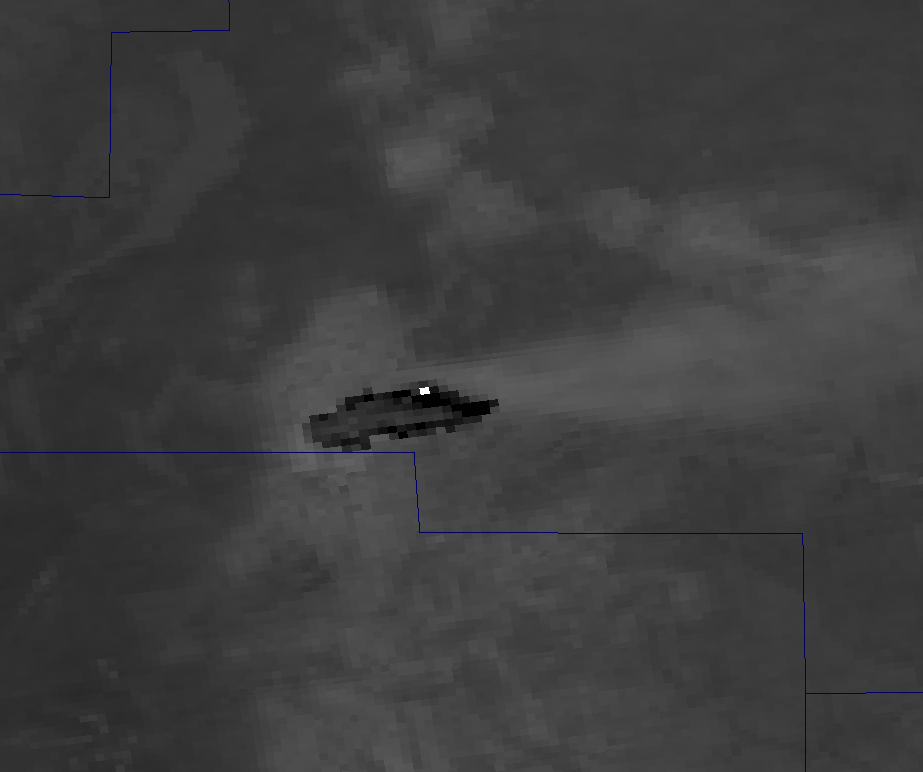

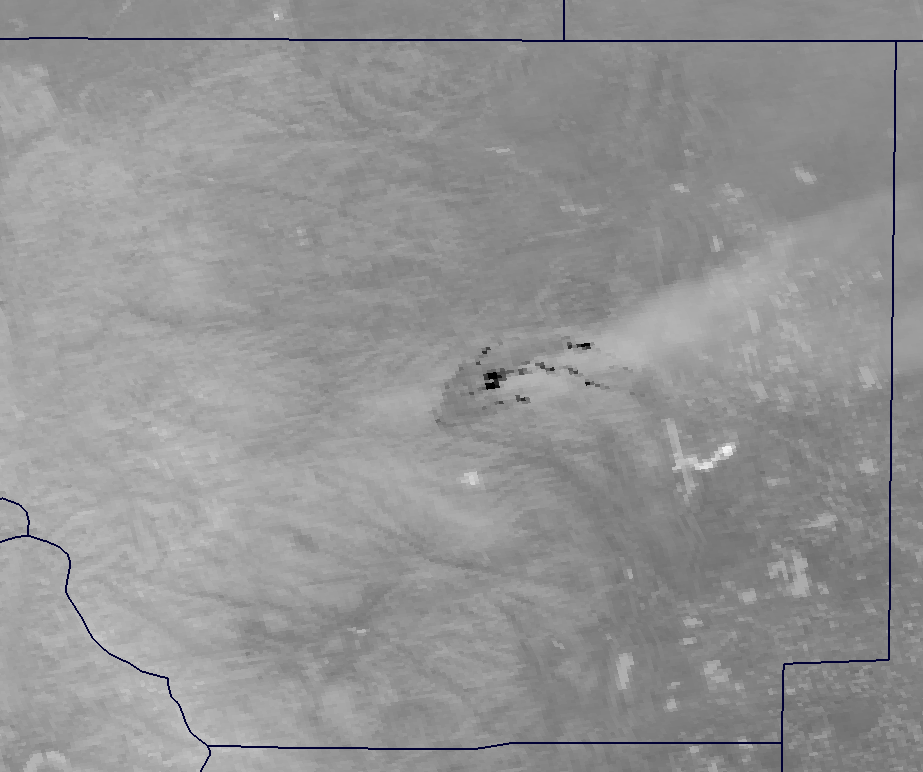

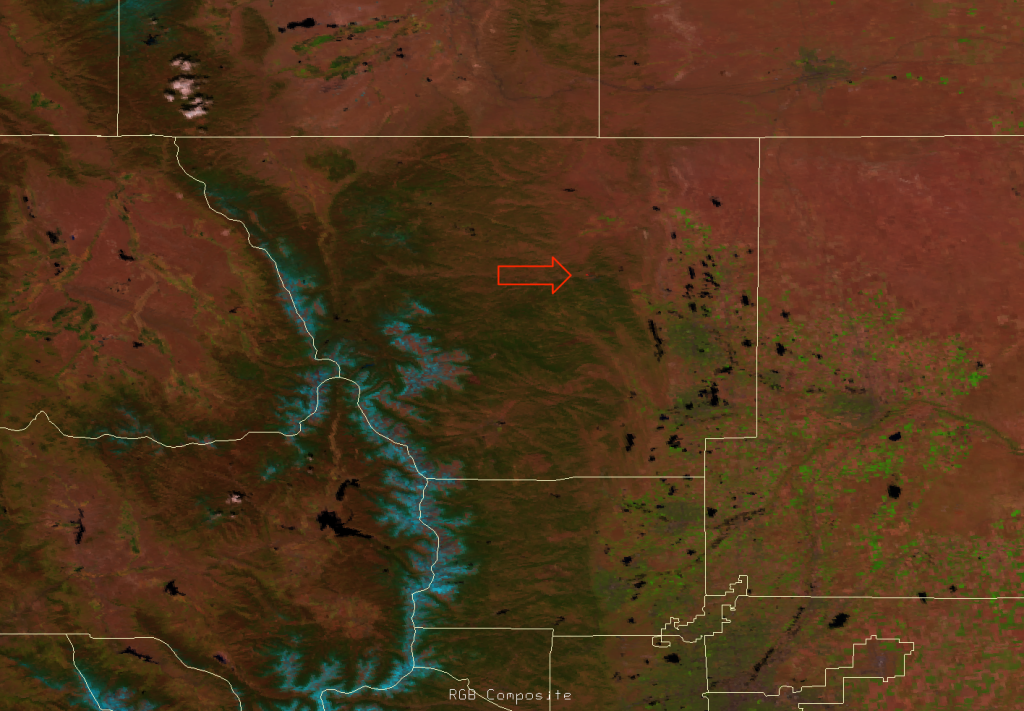

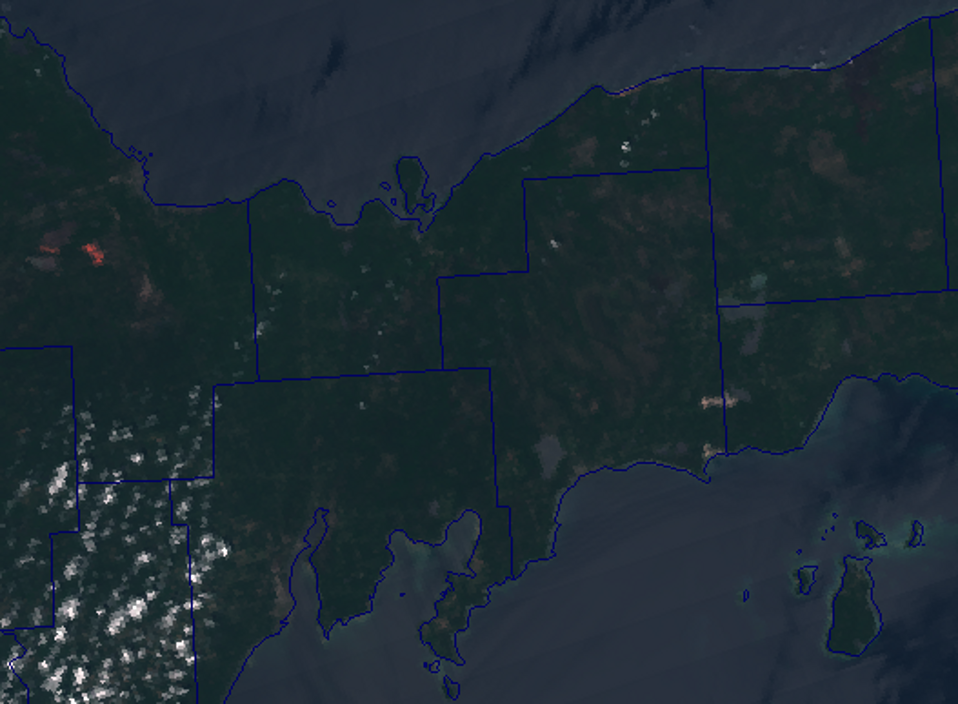

The highest brightness temperature in the burn area in this channel at this time was ~331 K. As we saw before with the Lower North Fork Fire, the high resolution false color composite of channels I-01, I-02 and I-03 is useful in highlighting the burn area:

Notice the large, brown area that coincides with the hot spot in the I-04 image. The combination of wavelengths used in this composite (0.64 µm [blue], 0.865 µm [green] and 1.61 µm [red]) is quite sensitive to the amount (and health) of the vegetation.

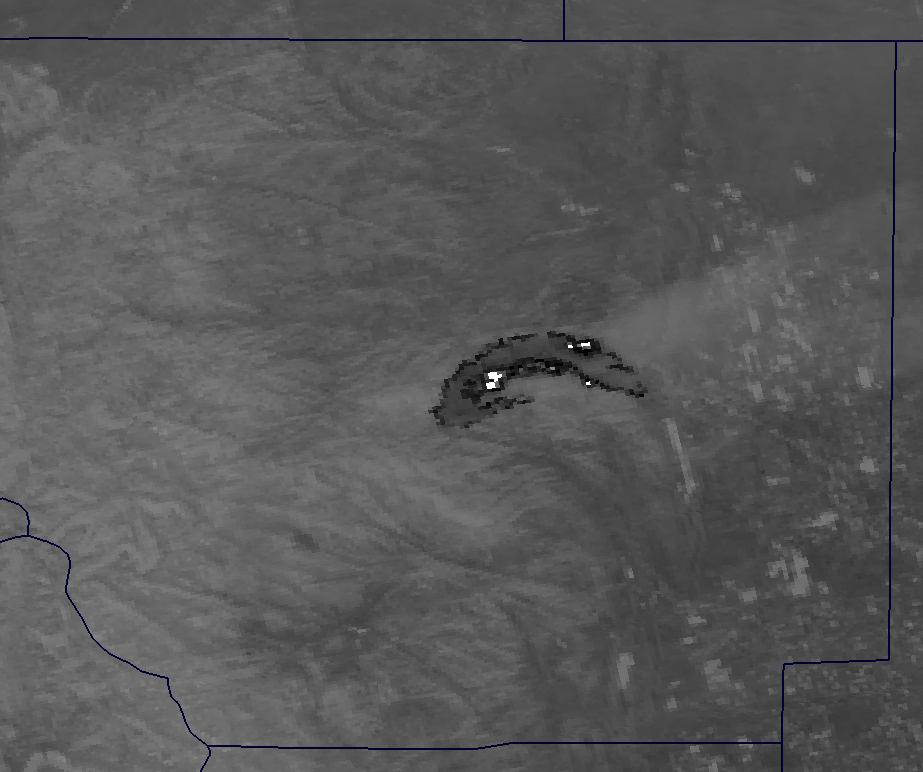

You might have also noticed several other interesting features in the image that show up better when you zoom in:

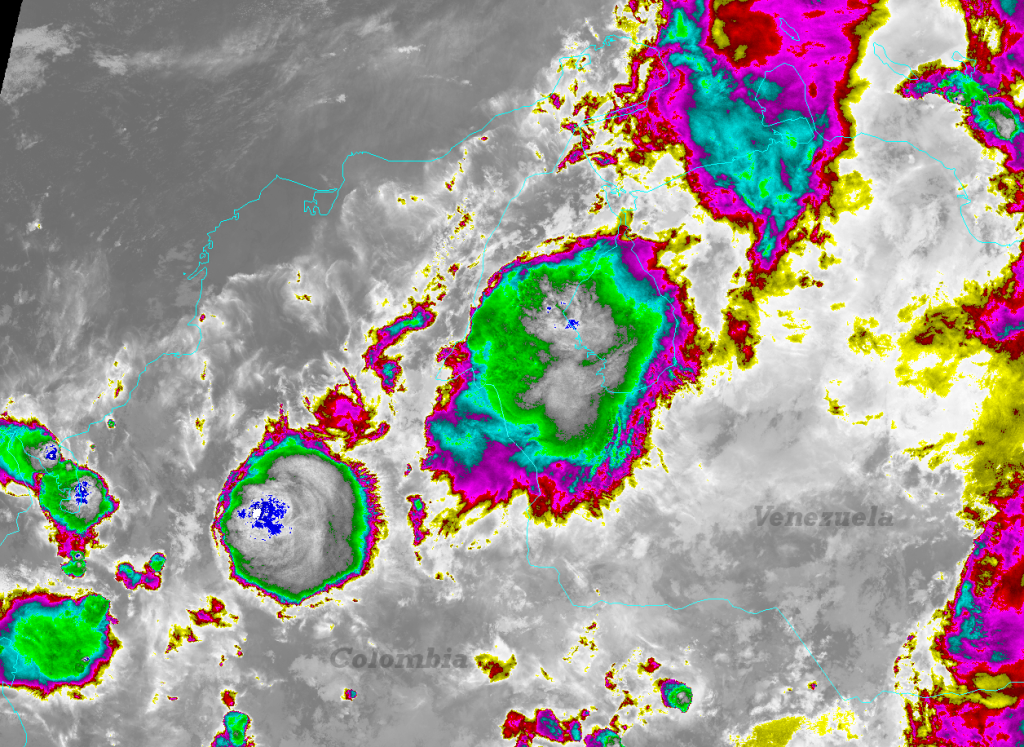

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan was based on mining for most of its history, and several large mines and quarries still exist, which VIIRS can easily see.

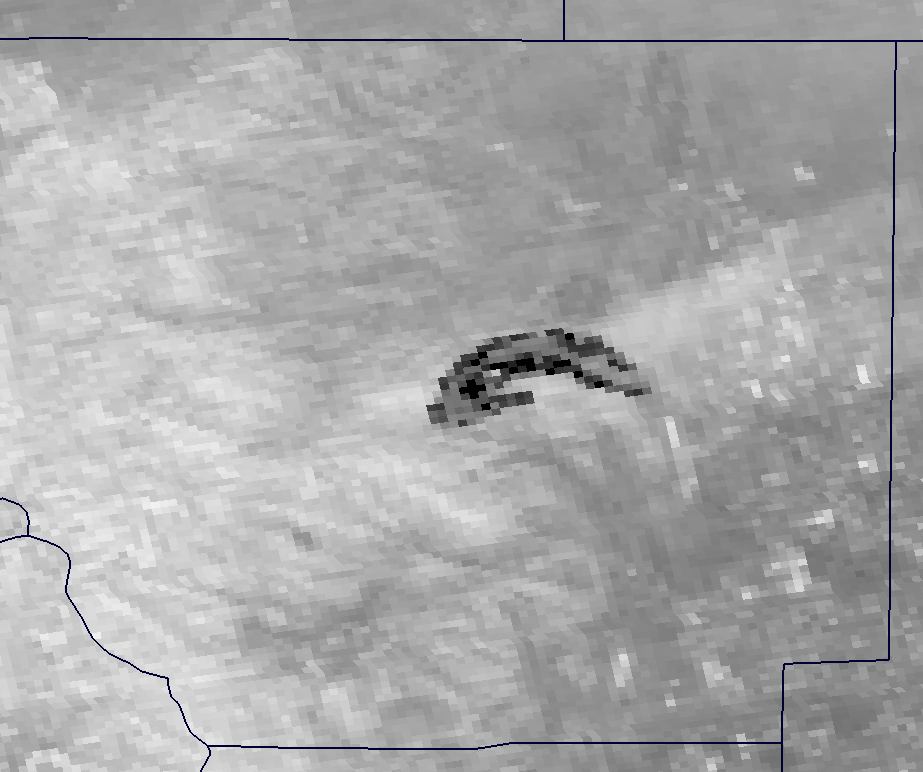

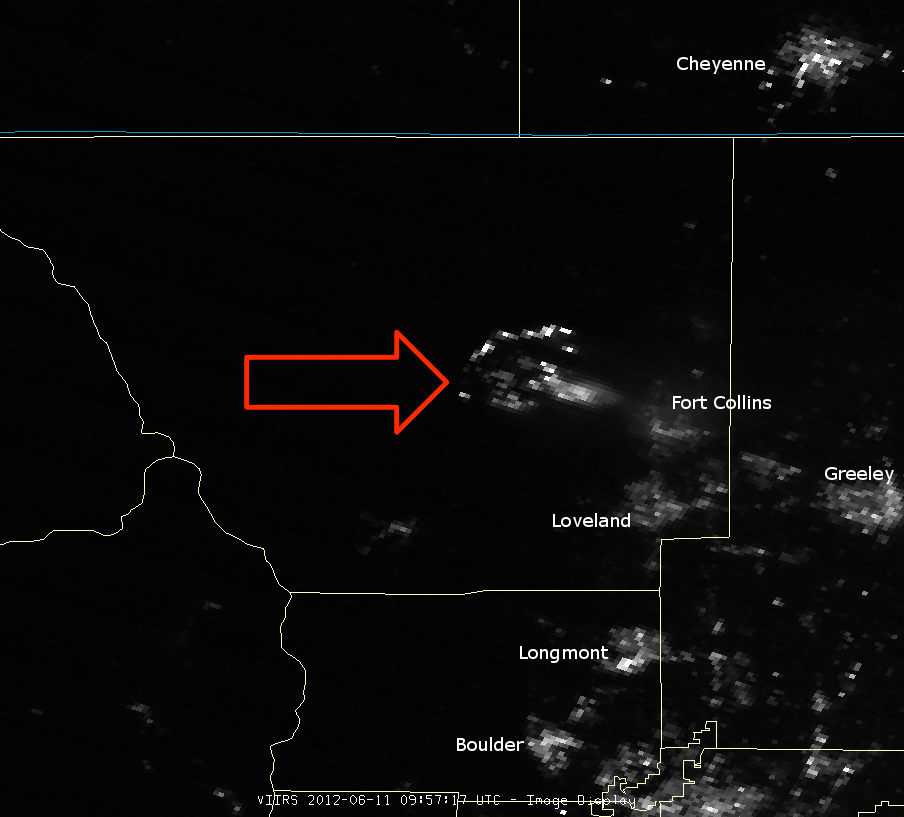

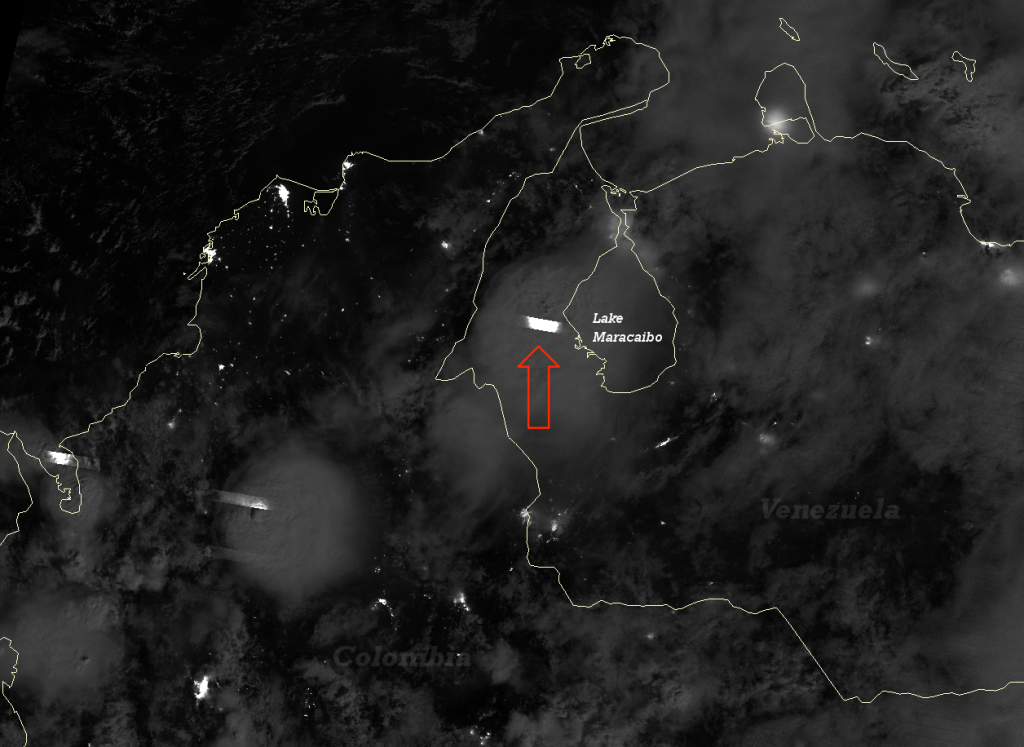

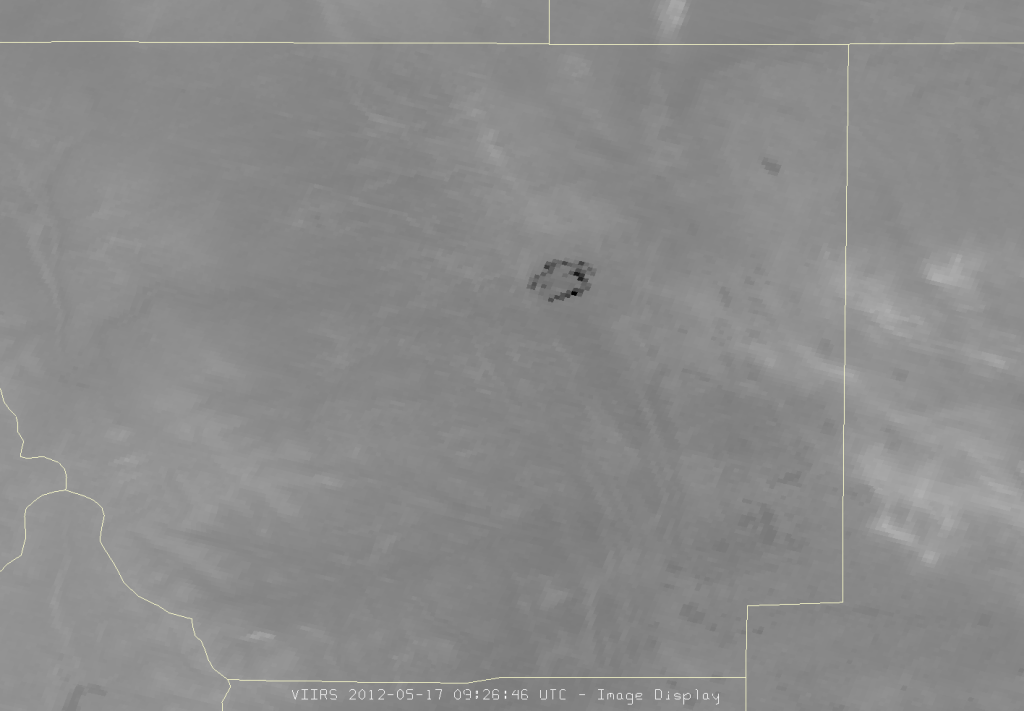

If you didn’t know any better, you might confuse the iron mine southwest of Marquette, Michigan with a frozen lake, or miraculously un-melted snow leftover from winter, since that is just what snow and ice look like in this kind of RGB composite. Compare that with the true color view of the same area:

In this case, the iron mine stands out as a bright red. Why?

The true color composite uses wavelengths at 0.48 µm (blue), 0.55 µm (green) and 0.67 µm (red). The red channel in the true color composite is actually in the red portion of the visible spectrum. The blue channel in the false color composite (0.64 µm) is also in the red portion of the visible spectrum.

This example shows that the iron oxide (rust) produced at the iron mine is highly reflective in the red portion of the visible spectrum. That’s what gives it the characteristic rust color. Iron oxide is not nearly as reflective at shorter or longer wavelengths, so it shows up blue when red wavelengths are used as the blue channel (as in the false color composite) and red when they are used as the red channel (as in the true color composite).

Let this be a lesson to anyone who uses the false color composite as part of a snow and ice detection algorithm. Snow and ice are not the only things to show up that color. You may be looking at a really large iron mine.