According to legend, Popocatépetl was a great warrior whose girlfriend, Iztaccíhuatl, died because her father was a jerk who lied. (An alternate story is that it was a rival warrior who was a jerk who lied.) Either way, Iztaccíhuatl was erroneously told that Popocatépetl died in battle, which caused her to die of grief. When Popoca, as he was known to his buddies, returned to find out that she was dead, he was very sad. Reports on what followed differ, but Popoca either died of grief himself, or committed suicide at the thought of living without Iztaccíhuatl. To commemorate these events, the gods turned them both into mountains. To this day, the mountain Popocatépetl spews out rock and ash and fire either because he’s still mad at what happened, or because it is his way of looking out for his girlfriend.

The name Iztaccíhuatl literally means “White Woman,” and is the name of the snow-covered mountain ~40 miles southeast of Mexico City. Popocatépetl literally means “Smoking Mountain,” and is the name given to the volcano just to the south of Iztaccíhuatl. It is one of Mexico’s most active volcanoes. Ole’ Popoca has recently begun to remind us that he is mad (or eternally vigilant).

The alert level was raised in mid-April after the volcano was heard rumbling and once again began spewing ash over the region. If you clicked on that link, you might have noticed this sentence:

“The joint NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP satellite snapped a picture of the ash cloud coming from Popocatépetl on April 16.”

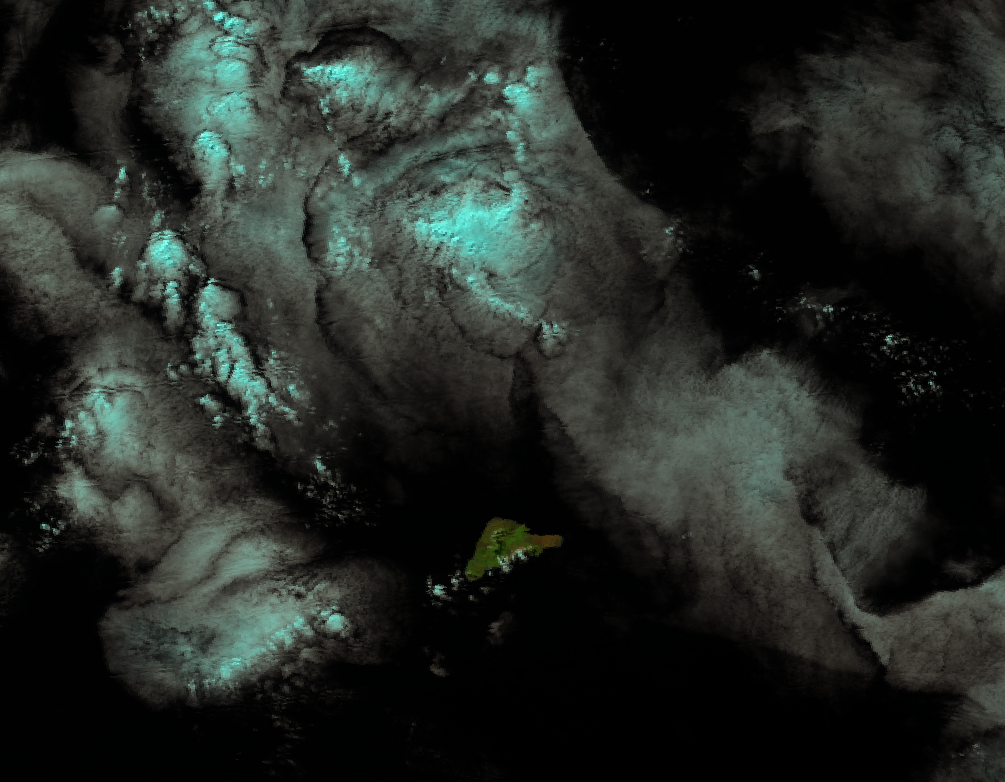

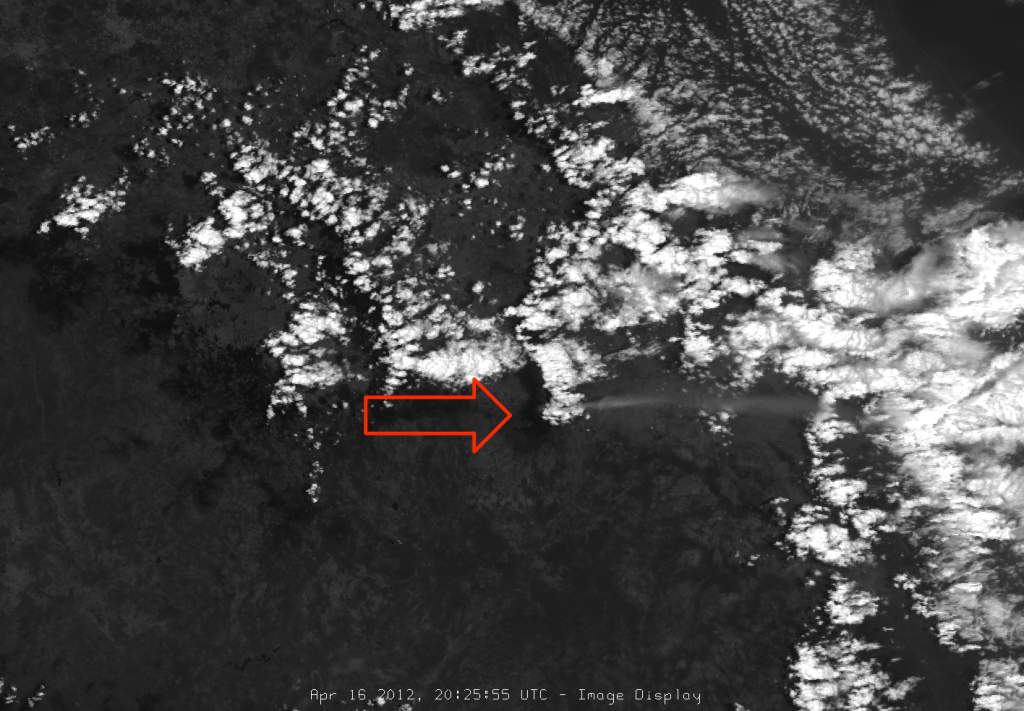

Although they forgot to include the picture in the article, VIIRS on board Suomi NPP did see the ash cloud. Here’s an image of the I-01 reflectance (white = 1, black = 0) taken by VIIRS on 16 April 2012 at 20:25 UTC:

The ash plume is pushed to the east by the winds surrounding the cloud-covered volcano (where the arrow is pointing). On a clearer day, you can see Popocatépetl, Iztaccíhuatl, Matlacuéyatl, and the tallest volcano in Mexico, Pico de Orizaba:

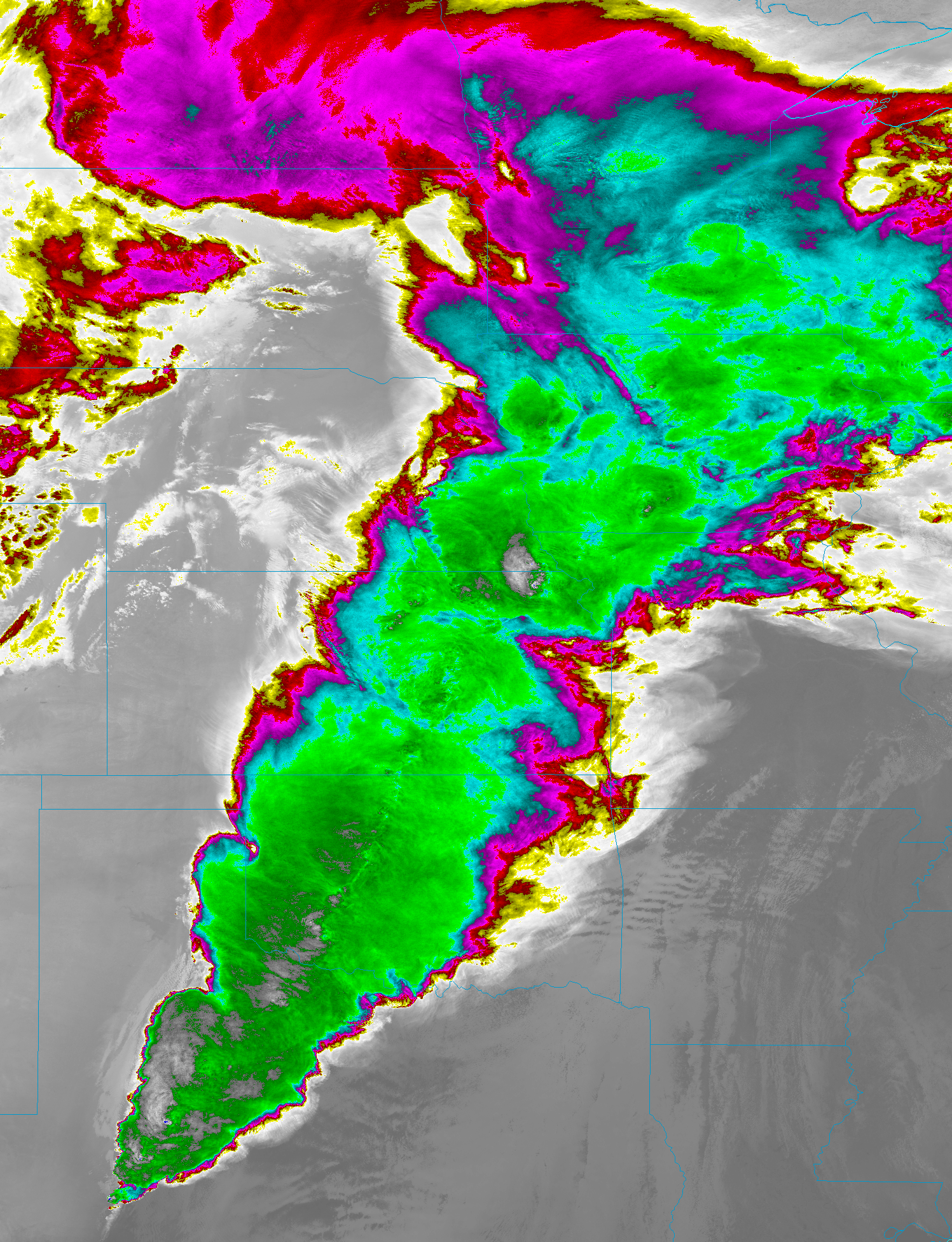

The above image is a false-color RGB composite of VIIRS channels I-01, I-02 and I-03 taken at 19:53 on 23 April 2012. The volcanoes and nearby urban centers have been identified and labelled. Pico de Orizaba, Popocatépetl, and Iztaccíhuatl are the first, second and third tallest mountains in Mexico, respectively, and are normally the only mountains in Mexico to be snow-covered year-round. The snow on top of Pico de Orizaba and Iztaccíhuatl is clearly visible in the image. Popocatépetl lost its snow during the 1990s when it became more active. But, you can see the cloud of ash and steam from the volcano in the image, which is not being blown around in the wind as much on this day. In fact, you can watch a time-lapse video of the steam and ash cloud from a Mexican government webcam from around the time of the Suomi-NPP overpass where you can see the clouds produced/influenced by The Smoking Mountain.

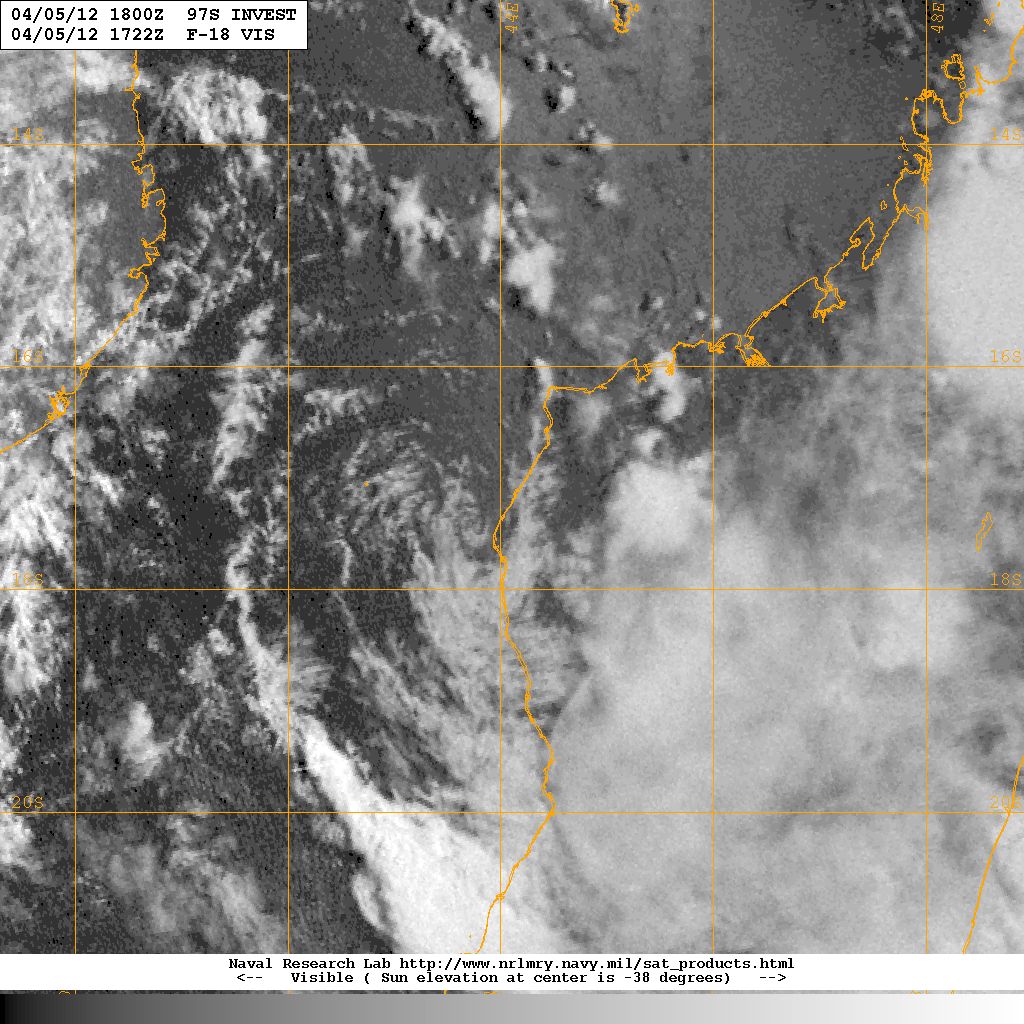

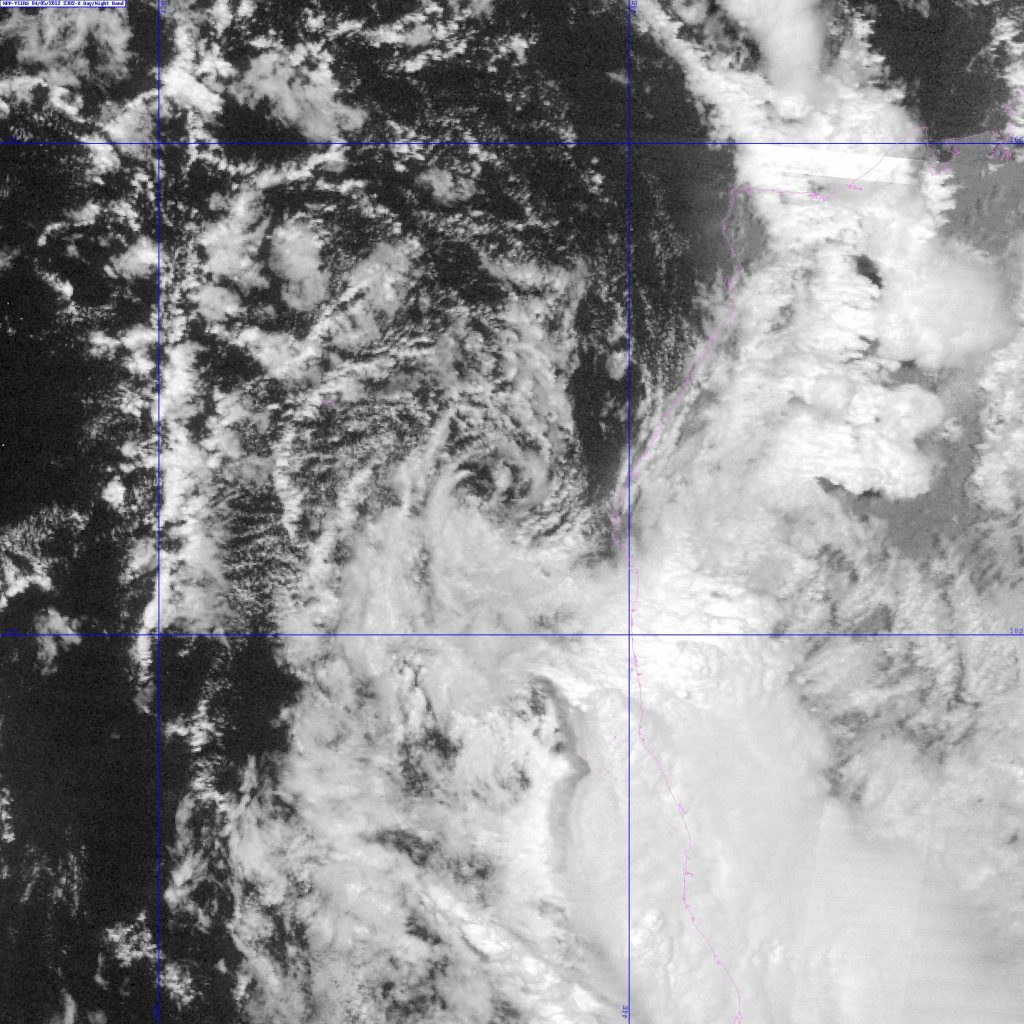

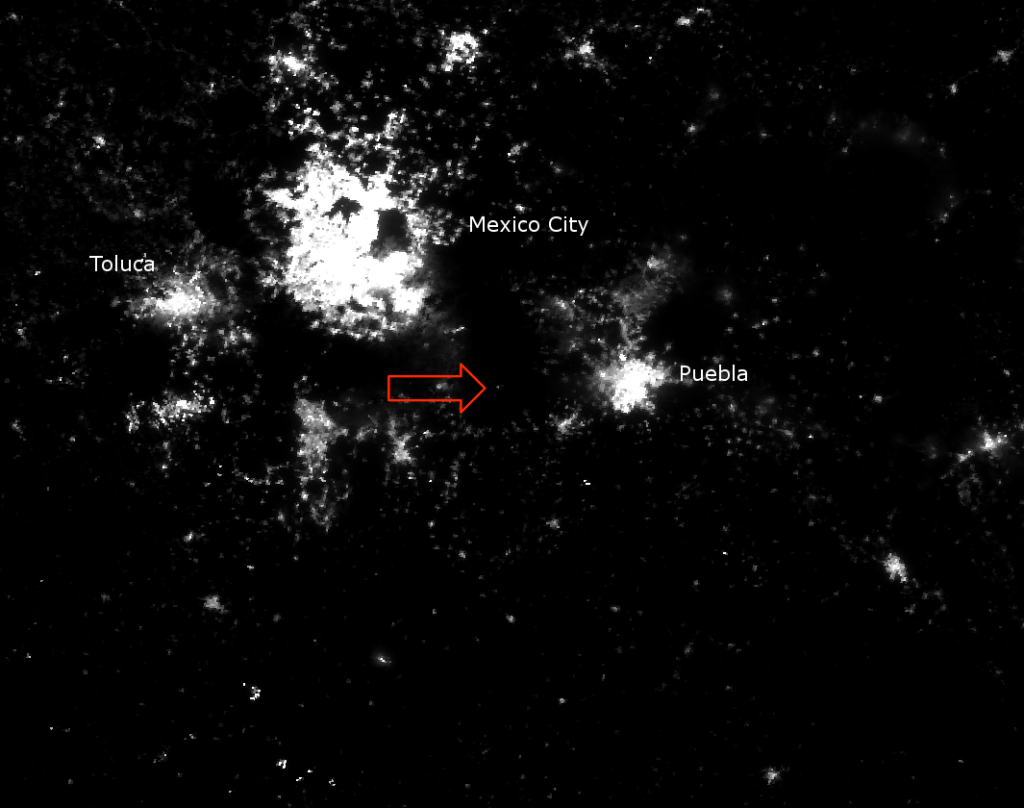

On 20 April 2012, a photographer captured this amazing image of Popocatépetl’s eruption of lava at night. Being near a new moon (which occurred on 21 April), the Day/Night Band (DNB) was able to see this lava eruption:

In the above images, the red arrows are pointing to the same spot – the top of Popocatépetl. The upper image is from the DNB at 07:58 UTC on 20 April 2012, the lower image is from I-01 at 19:53 UTC on 23 April 2012 (the same time as the RGB composite). If you were to overlay the images on top of each other, you would see that the light source visible in the DNB image is right at the top of the volcano. Since there are no towns up there, and people surrounding the volcano have been evacuated, the light is coming from the erupting lava.

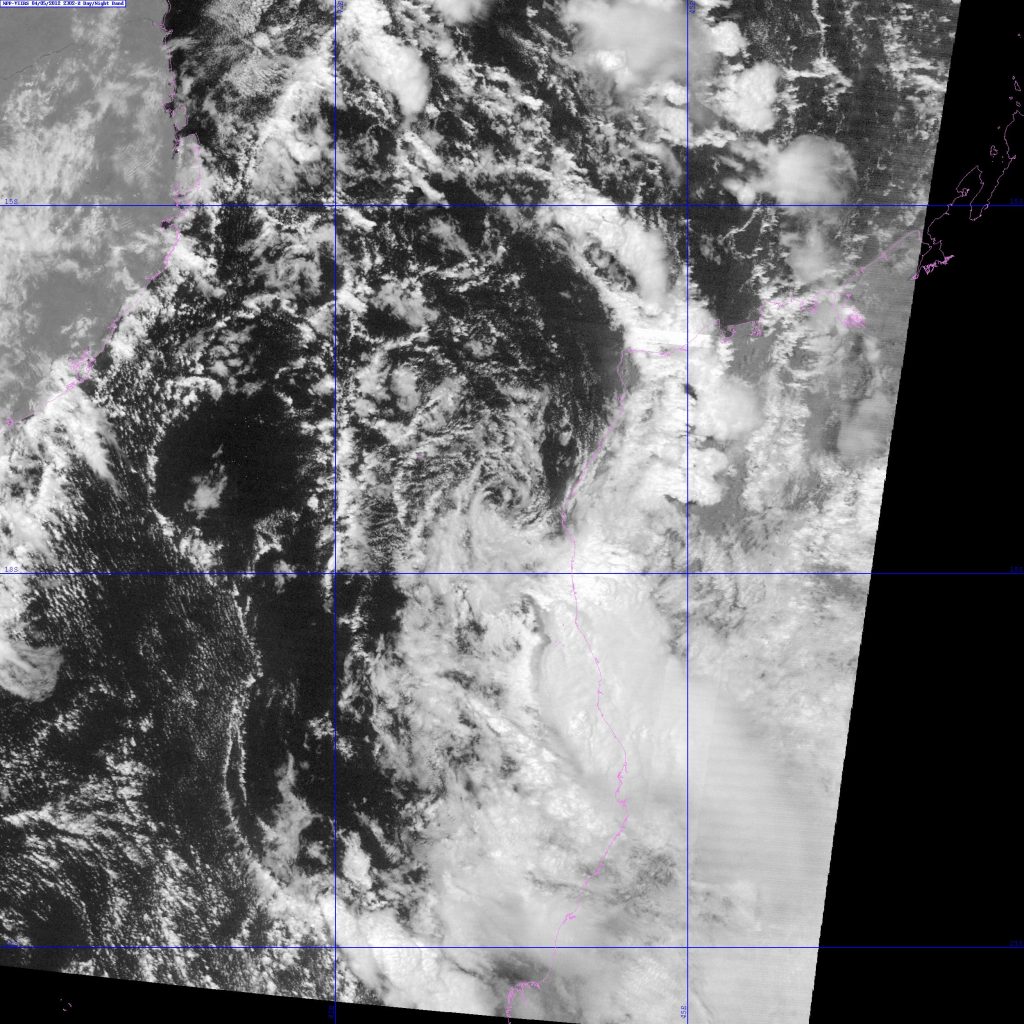

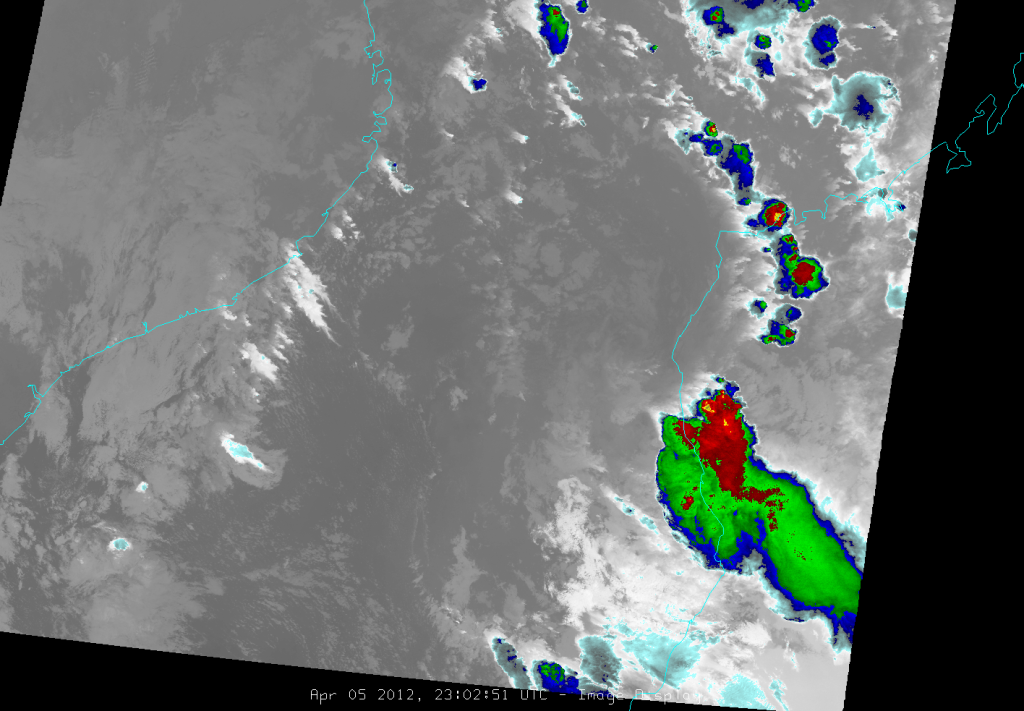

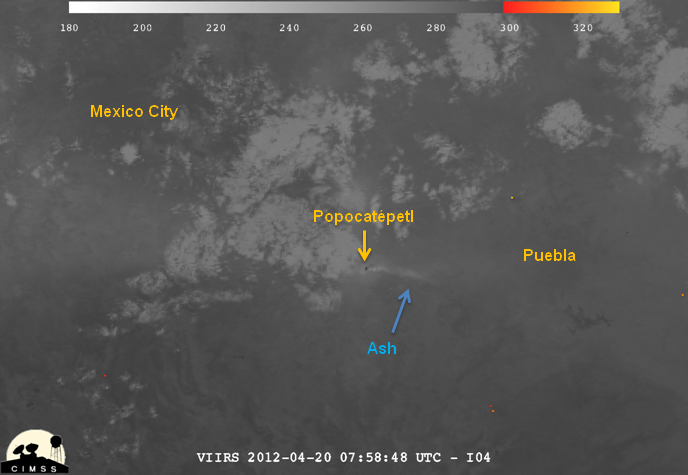

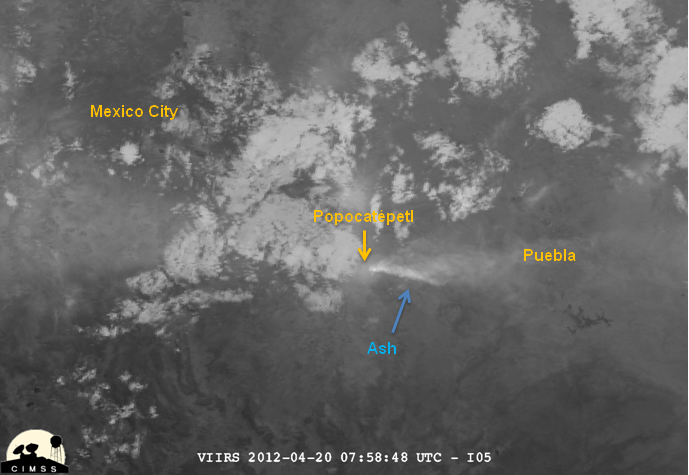

CIMSS provided these images of the volcano and ash plume at night (the same time as the DNB image above), which were visible in channels I-04 and I-05:

The upper image is the I-04 image. Channel I-04, at 3.74 µm, is very sensitive to hot spots such as wildfires or, in this case, volcanic eruptions. The dark (warm) spot identified is the heat signature of the molten rock that is erupting from the volcano. The cooler (brighter) ash cloud is visible in the I-04 image, but it shows up more clearly in the I-05 (11.45 µm) image underneath it.

Someone compiled a time-lapse series of images (14 April – 22 April) of Popocatépetl from a “NASA satellite” (presumably GOES-13) and posted the video to YouTube, which you can watch here.

Given its proximity to Mexico City, Popocatépetl is on the list of dangerous volcanoes to watch out for. The folks at WIRED are keeping their eye on it. Hopefully, Ole’ Popoca is just letting off a little steam, and not planning to get real violent. His girlfriend died a long time ago – it’s time to just let it go already.