If you pay attention to tropical cyclones, that headline may be confusing. Unlike the Super Cyclone in the Indian Ocean we just looked at, Super Typhoons are not rare in the Pacific Ocean. There have been 5 of them this year. What is rare is a typhoon that is estimated to be one of the strongest storms ever recorded in human history. I am, of course, speaking about Typhoon Haiyan, which the Philippines will forever remember as Yolanda.

If you don’t pay that much attention to tropical cyclones, you should be asking, “How do we know it is one of the most intense tropical cyclones ever in recorded human history?” You may also be asking, “Why does it have two names?” And, “What is the difference between a typhoon and a hurricane and a tropical cyclone?”

I’ll answer those in reverse order. Typhoons, hurricanes and tropical cyclones are different names given to the same physical phenomenon. If it occurs in the Atlantic Ocean or the Pacific Ocean north of the Equator and east of the International Date Line, it is called a “hurricane”, a name that was derived from Huracan, the Mayan god of wind and storms. If it occurs in the Pacific Ocean north of the Equator and west of the International Date Line, it is called a “typhoon”, which may come from the Chinese “daaih-fùng” (big wind), Greek “typhōn” (wind storm) or Persian “ṭūfān” (a hurricane-like storm). Anywhere else and it is a “cyclone” – a term for rotating winds, which ultimately comes from the Greek “kyklos” (circle).

Why does it have two names (Haiyan and Yolanda)? Different parts of the world use different naming conventions. When it comes to typhoons, the United States uses the naming convention of the Japan Meteorological Agency and the World Meteorological Organization. The Philippines come up with their own name list. That’s why we know it as Haiyan, while Filipinos know it as Yolanda.

Now, was this really the most intense tropical cyclone in all of recorded human history? That question is more difficult to answer. It depends on how you define “intensity”. Is it the lowest atmospheric pressure at the Earth’s surface? Is it the highest 1-minute, 5-minute or 10-minute average wind speed at the Earth’s surface? Is it based on structural damage? Deaths?

The last two, damage and deaths, are better measures of the storm’s impact, rather than its physical strength. So, we’re going to focus on how one would measure the physical strength of the storm.

Barometers, used to measure pressure, have been around for about 400 years. Anemometers, which measure wind speed, have been around in their modern form for about 160 years. (It is also possible to estimate wind speeds from Doppler radar, technology that has been around since World War II, although these estimates are not as accurate as anemometers.) The primary issue is getting these instruments inside a super typhoon (and not having them be destroyed in the process).

It is possible to attach an anemometer and a barometer to an airplane, then fly the plane into the storm to measure the wind and pressure (which is done for almost every hurricane on a path to hit the United States), but not every country is wealthy enough to afford their own research aircraft. Plus, it’s tough to find anyone crazy enough to fly into a storm as strong as Haiyan. Here is a story of why “hurricane hunting” isn’t always a good idea.

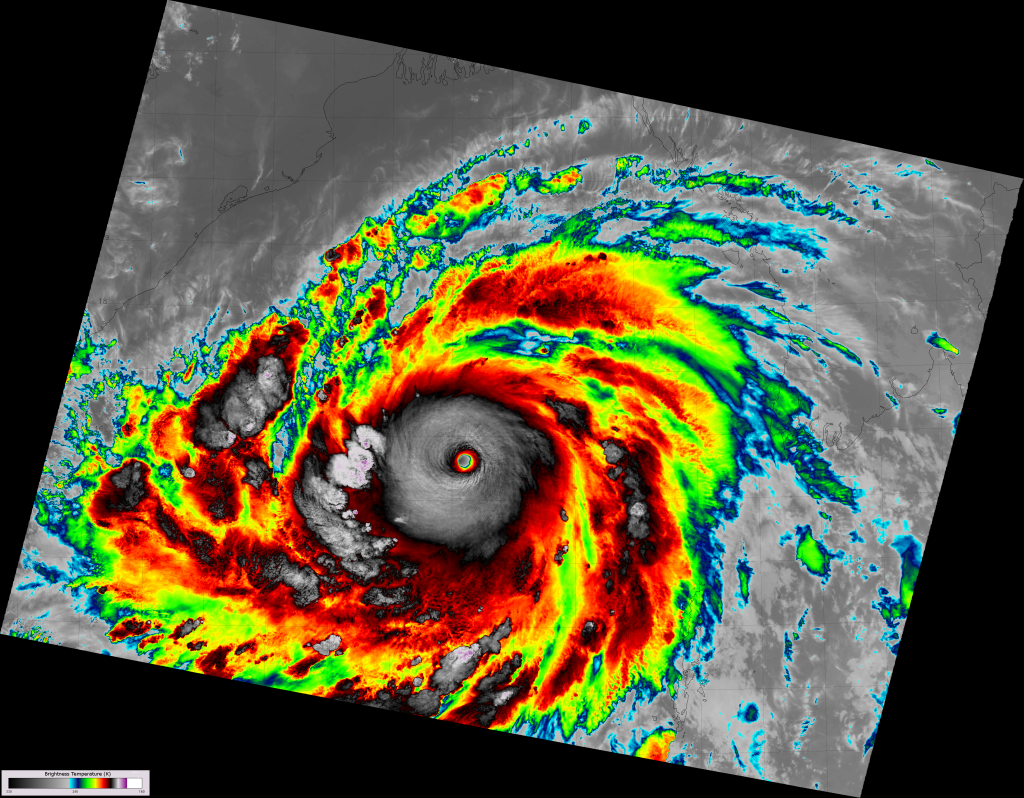

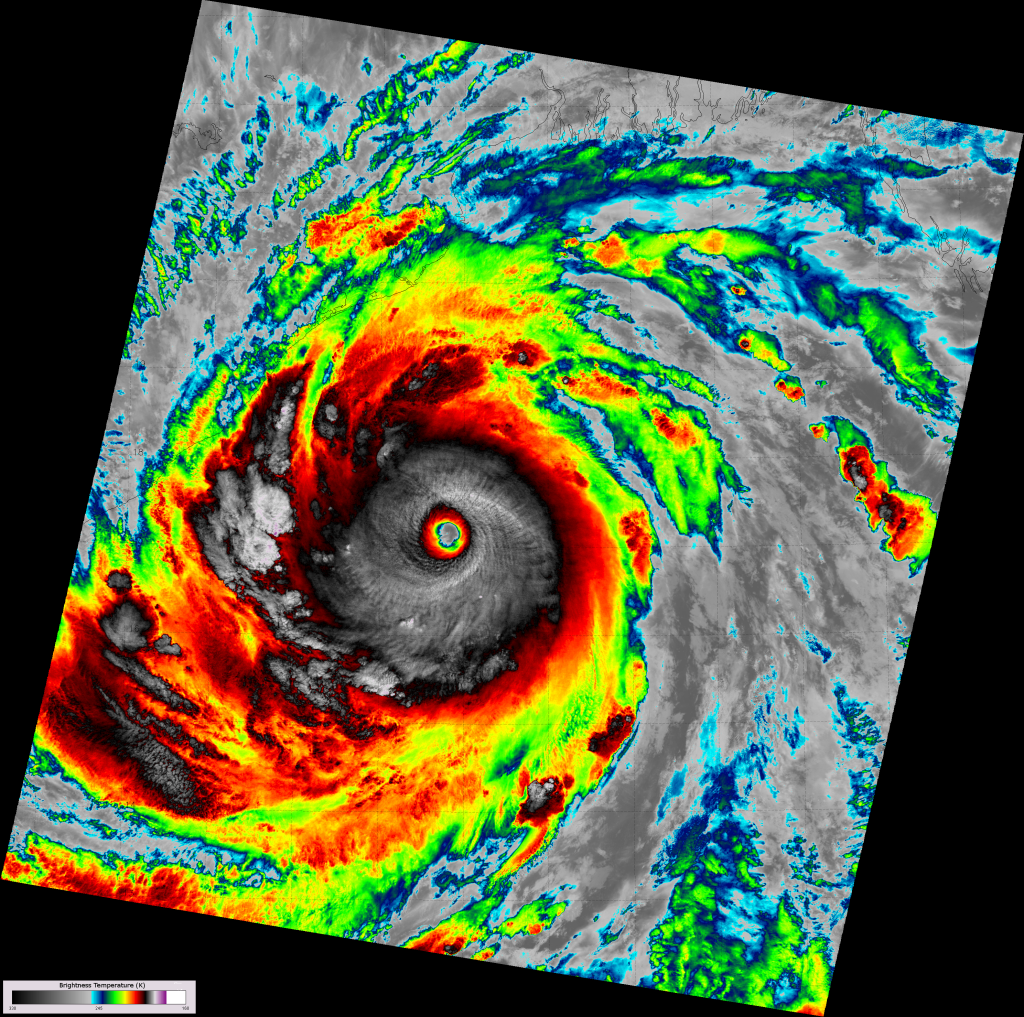

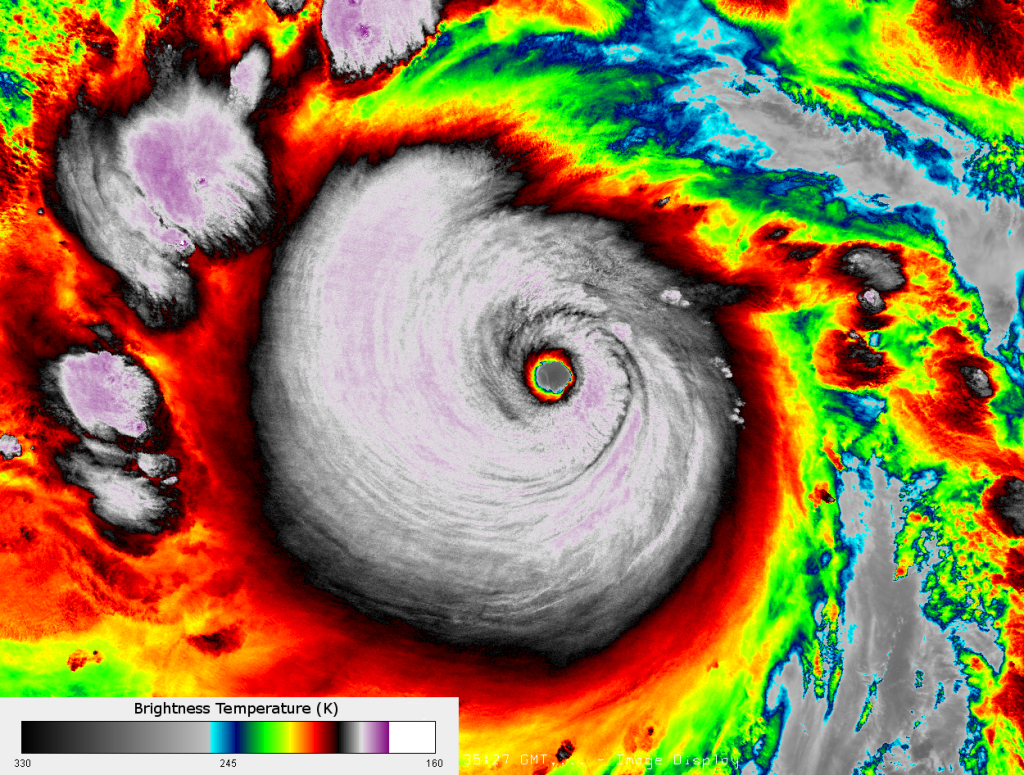

Weather satellites, which have been around for 50 years, can view these storms from afar (with no risk of being damaged by them) and are the primary way to determine wind speeds and pressures (particularly when the storm is out over the ocean, where there aren’t many barometers and anemometers). The method to determine the strength of a storm from satellite is called the “Dvorak Technique”, developed by Vernon Dvorak in the 1970s, and discussed in detail here. Basically, the algorithm takes the current appearance of the storm in visible and infrared wavelengths (how symmetric it is about the eye, what is the brightness temperature in the warmest pixel in the eye, what is the brightness temperature of the coldest ring of clouds around the eye, and so on), along with the recent history of the storm’s appearance and relates that to a storm’s central pressure and maximum sustained wind speed based on an empirical relationship. For those storms that have been viewed by both satellite and aircraft, the Dvorak Technique has been shown to be pretty accurate: over 50% of storms have wind speed errors less than 5 knots, and overall root-mean-square errors of 11 knots.

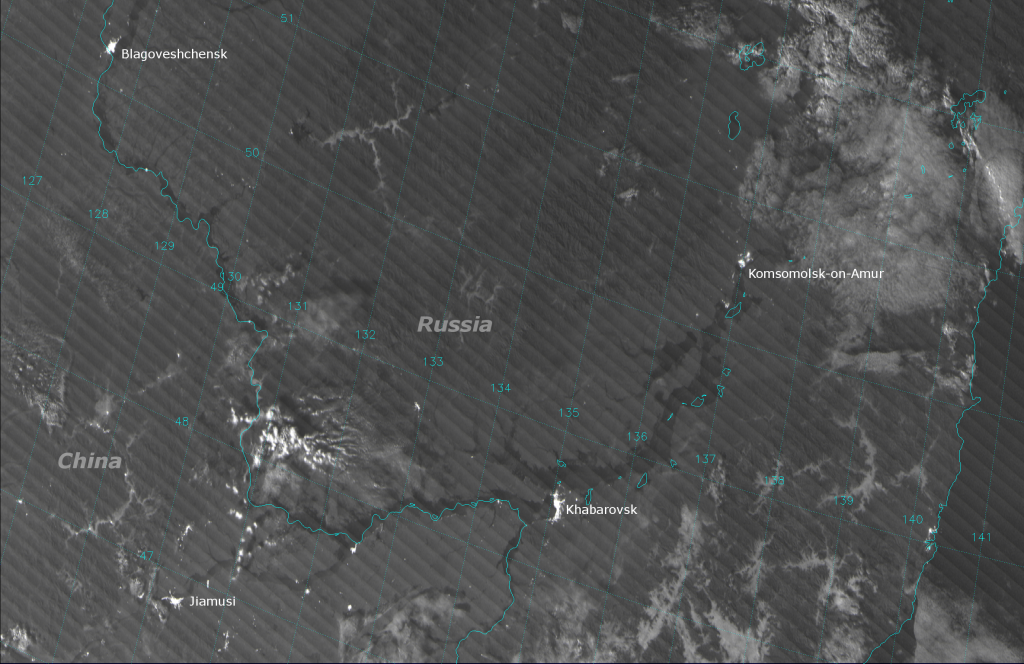

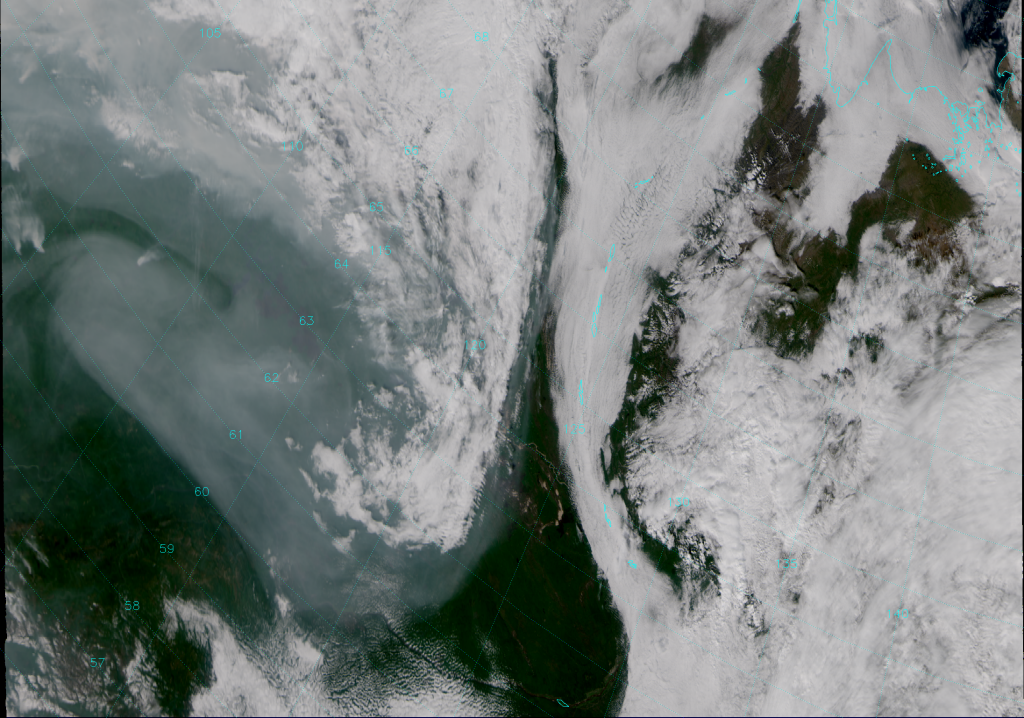

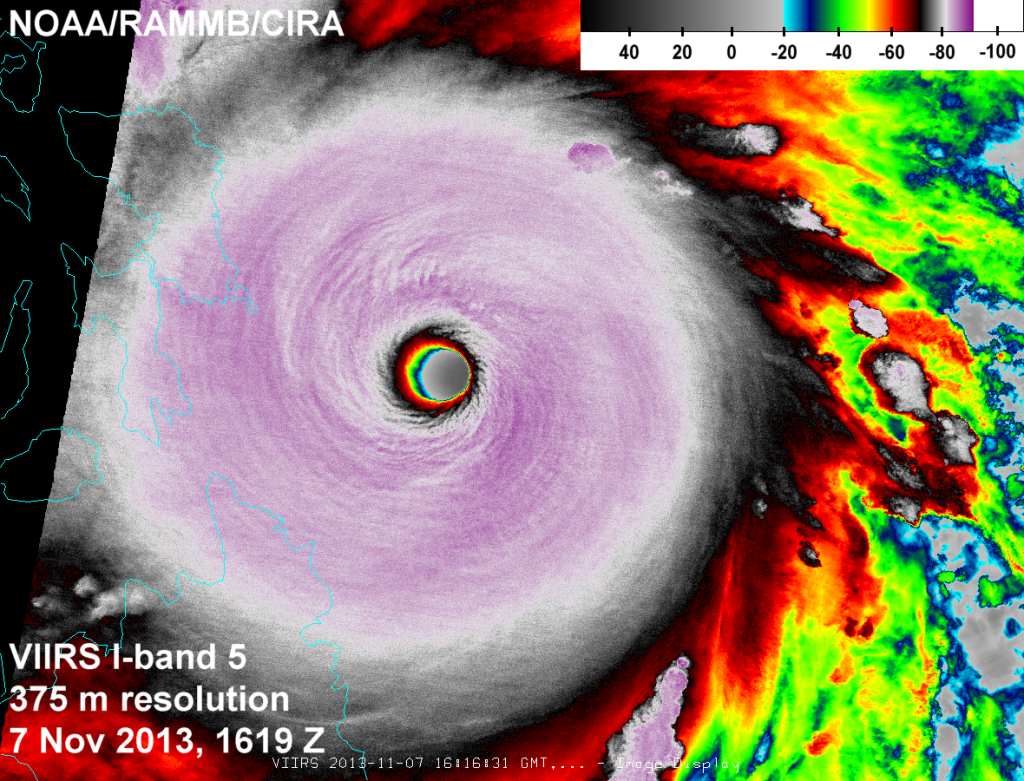

The image loop from MTSAT above, and the VIIRS images below of Haiyan (Yolanda) highlight the relevant points the Dvorak Technique keys on when determining its intensity: a well defined eye with warm infrared brightness temperatures (up to +23 °C), a ring of cold clouds surrounding the eye (the purple color corresponds to temperatures less than -80 °C), and it’s hard to find a storm more symmetric than this one.

As a quick aside about the power of VIIRS, Haiyan was right at the edge of the scan when the image above was taken. Look at the impressive detail even at the edge of scan! See if you can beat that, MODIS!

Using Dvorak’s method, Haiyan (Yolanda) achieved the maximum possible value on the “T-number” scale: 8.0. That puts the maximum sustained winds above 170 knots (315 km h-1 or 195 mph!) and the sea-level pressure below 900 mb (hPa), according to the scale. You can’t get any stronger than that because the data used to develop the empirical relationship doesn’t contain any storms stronger than that. We’ve reached signal saturation on the Dvorak “T-number” scale. (And the Saffir-Simpson scale, and the Beaufort scale.) All we can say is Haiyan right up there with the strongest tropical cyclones ever observed. We can also say that Haiyan was the only storm to make landfall as an 8.0 on the “T-number” scale. But, beyond that, we would need actual in situ observations to know just how strong Haiyan (Yolanda) really was.

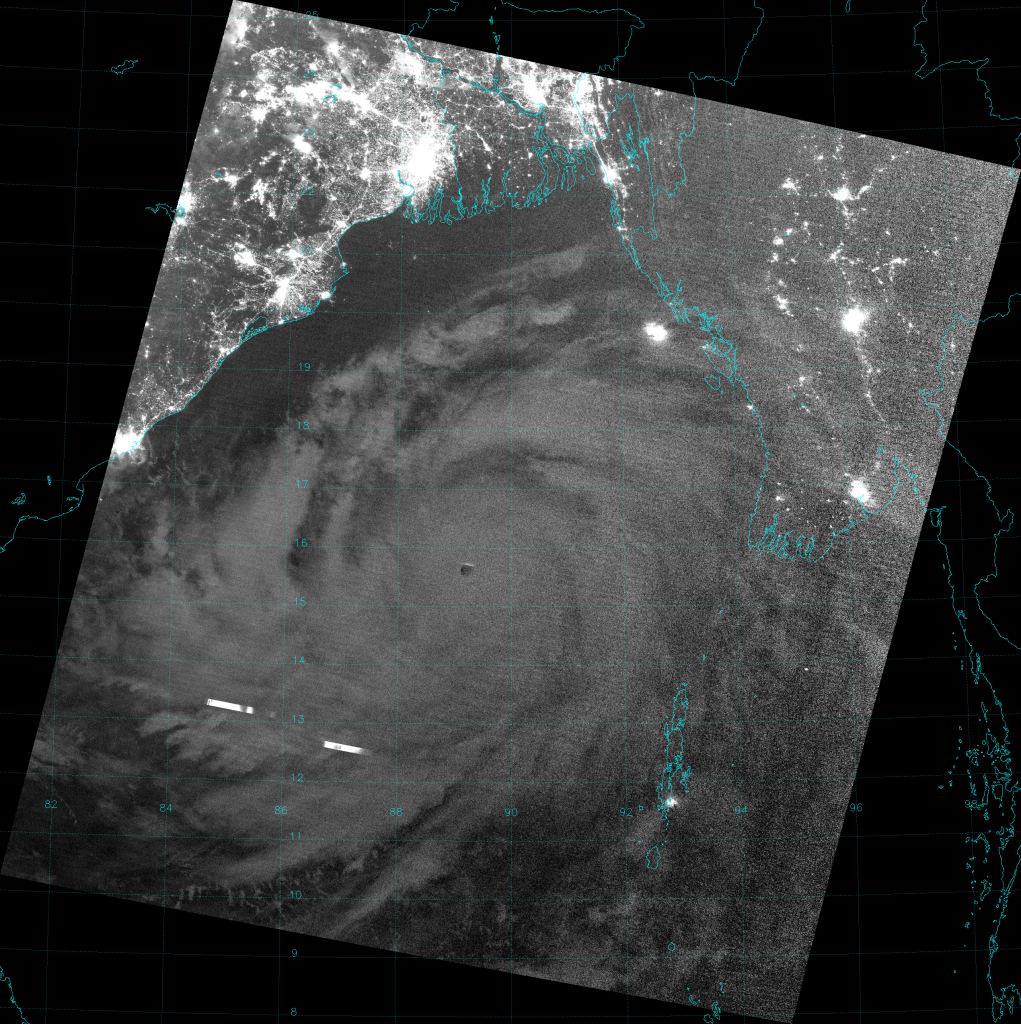

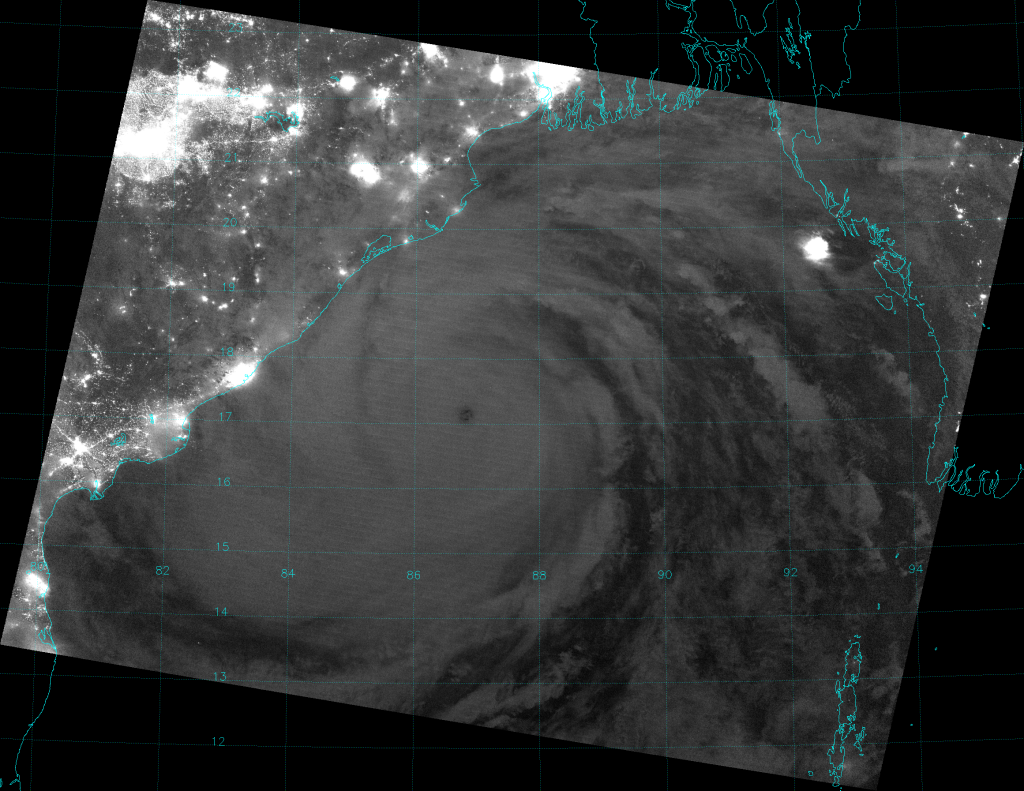

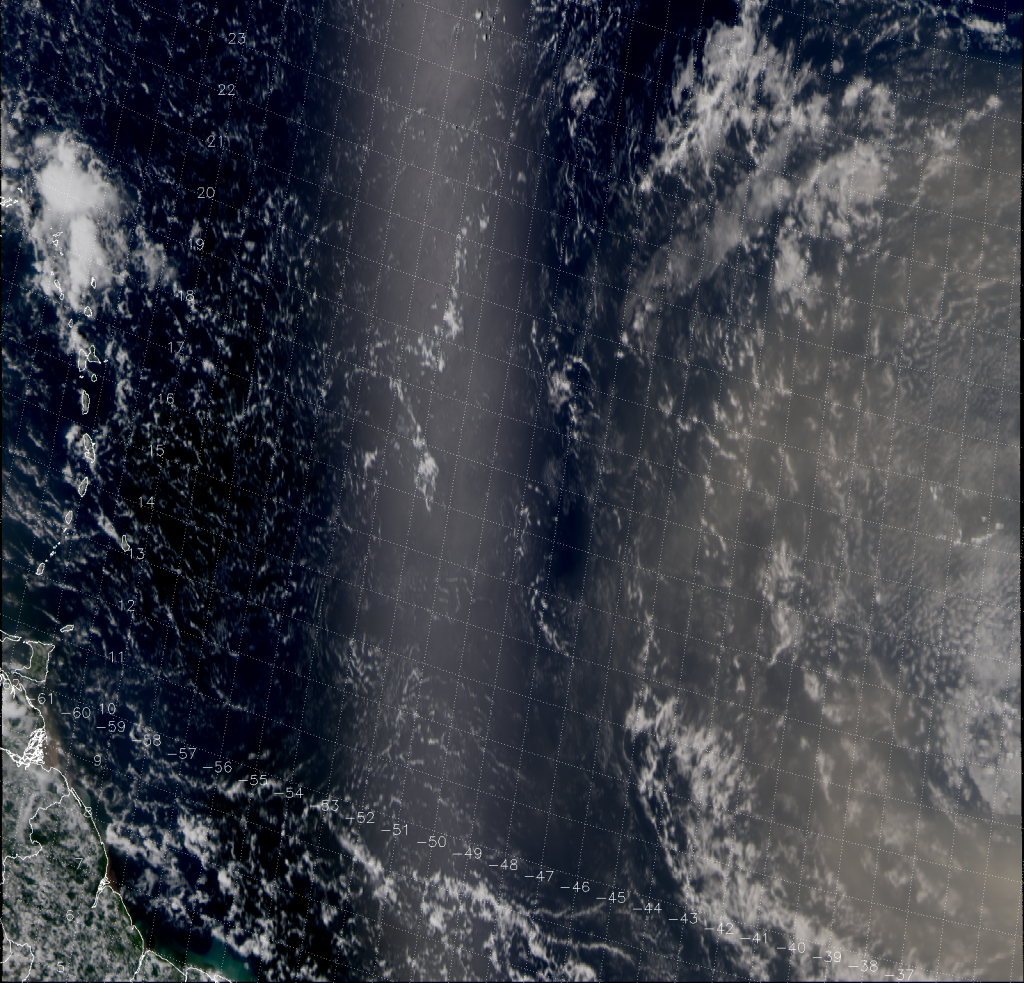

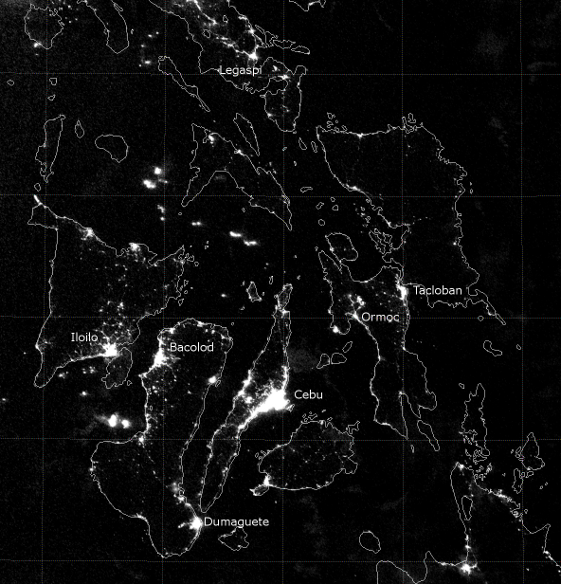

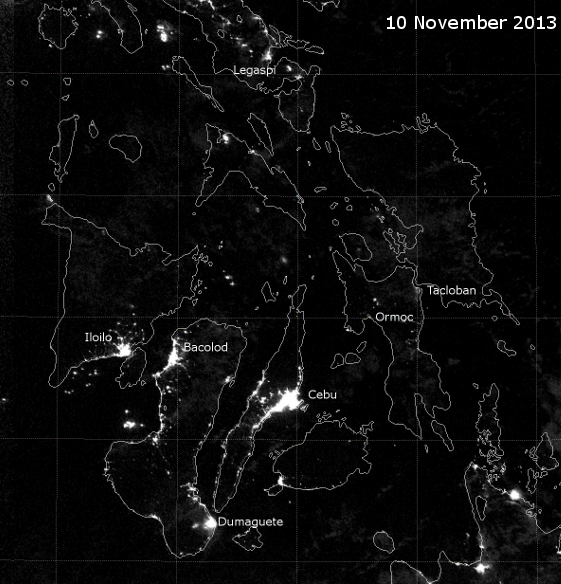

As expected, one of the strongest typhoons ever to make landfall caused some power outages. The Day/Night Band on VIIRS captures it well:

Did you notice the vertical bar in the above image that you can click on? Slide it left to right to see the differences in the amount of city lights (and nocturnal fishing activities) before and after Haiyan (Yolanda) made landfall. Tacloban was, of course, one of the hardest hit heavily populated areas. As you can see from radar, it took a direct hit from the eyewall.

With winds estimated at 195 mph, Haiyan (Yolanda) was like an EF-4 tornado. A 30-mile wide EF-4 tornado that lasted for several hours.

UPDATE: I have been notified that the above sliding bar trick in the Day/Night Band images above doesn’t work in all browsers (or for all operating systems). If that’s the case for you, click on the image below, then on the “1000×1000” link below the banner to see the high resolution animation.

The first two images in the animation show the Day/Night Band images from the nighttime overpasses on 31 October and 9 November 2013. The last two frames (one with the map plotted and one without) highlight the differences in these images by creating an RGB composite of the before and after images. Power outages show up as red in this composite. Areas that have kept their power show up a golden color. Areas with light after the storm, but not before the storm, show up green. In this case, green areas highlight where boats were after the storm, and where clouds scattered the city lights over a larger area than they appeared to be before the storm, when there were no clouds overhead. It’s another way to look at power outages in the Day/Night Band.