Ranger Road Fire

February 20th, 2026 by Jorel TorresOn 17 February 2026, the NWS Storm Prediction Center (SPC) issued an Extreme Fire Weather Outlook for the central and southern high plains, stretching from southwest Nebraska to the Oklahoma and Texas Panhandles. The outlook relayed the increased fire danger over the region, which was forecasted for high winds and low relative humidities. Abundant dry fuels were also present, which if fires were to ignite, that could support rapid fire spread across the domain. During the mid-morning of 17 February 2026, numerous fires erupted over the Oklahoma Panhandle and southwest Kansas. This blog entry focuses on the largest fire that ignited, the Ranger Road Fire. As of 19 February 2026, the fire burned approximately 283,000 acres.

Using the 5-minute, shortwave infrared imagery from geostationary satellites, one can observe the Ranger Road Fire’s initial hotspot (seen at ~1716Z, in white and then red pixels) in the midst of cloud cover overhead. The fire rapidly spreads to the northeast, eventually shifting eastward as a front passes through the region. Also, notice the other fire hotspots nearby, especially the fires near Woodward, OK, where a few structures were destroyed.

GOES ABI 3.9 um from 15Z, 17 February 2026 to 15Z, 18 February 2026

Surface map analysis shows a strong low-pressure system that moved off the Rockies and entered into the northern high plains. As the system moved east, it contained an elongated cold front that extended into the southern high plains, which supported fire spread across Oklahoma and Kansas.

Surface Map Analysis from 18Z, 17 February 2026 to 06Z, 18 February 2026

The VIIRS Fire Temperature RGB estimated the fire intensity of the Ranger Road Fire in a qualitative way. The RGB depicts the fire pixels in red, orange, yellow and white: where white pixels indicate the most intense fires. In the animation below, the fire pixels align with the narrow fire perimeter. Notice, how the fires spread to the northeast, as water clouds (blue) and ice clouds (dark green) move away from the fires.

VIIRS Fire Temperature RGB from 1840Z – 2020Z, 17 February 2026

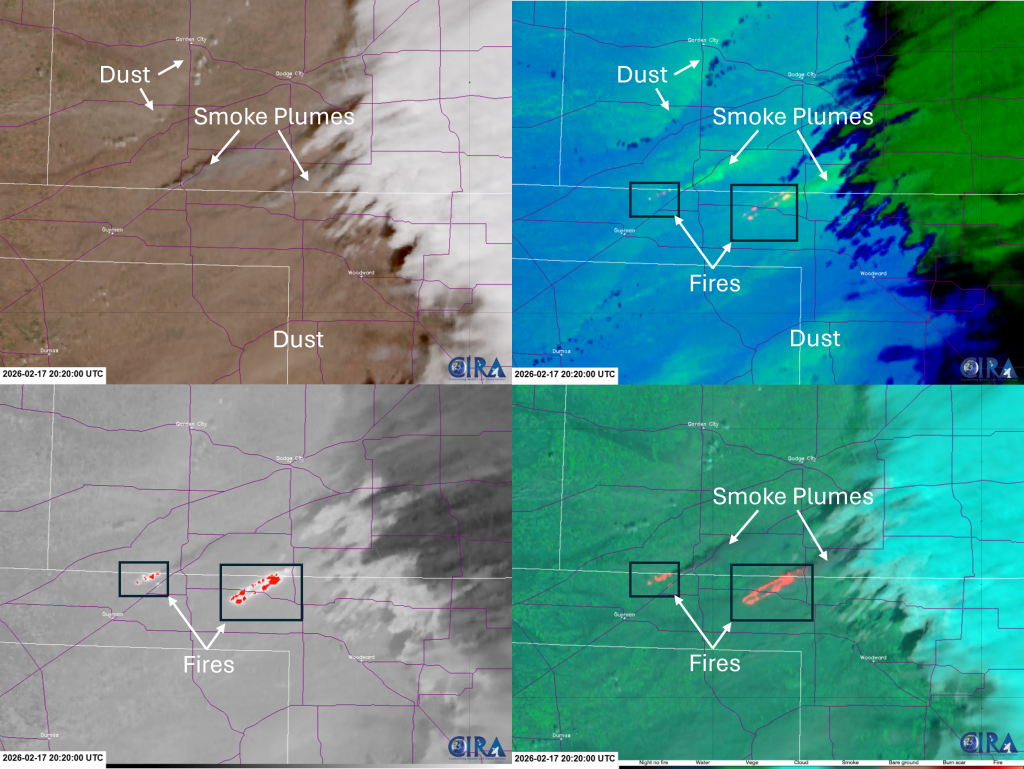

A 4-panel of VIIRS imagery is provided to show the additional data that can be used to view the fire hotspots, the smoke plumes, and dust that was lofted and blown, due to high winds. The 4-panel consists of GeoColor (top-left), Dust-Fire RGB (top-right), 3.7 um (M12), and the Day Fire RGB at 2020Z, 17 February 2026. Labels are provided to indicate some of the features in the imagery.

VIIRS 4-Panel: GeoColor, Dust-Fire RGB, 3.7 um (M12) and Day Fire RGB at 2020Z, 17 February 2026

On 19 February 2026, the burn scar, ash (produced from the Ranger Road Fire), and ambient dust were also captured from geostationary and polar-orbiting satellites. Refer to the CIRA social media link below.

Posted in: Uncategorized, | Comments closed

Fractured Ice: Lake Erie

February 13th, 2026 by Jorel TorresA significant chunk of ice fractured across Lake Erie last weekend, where an 80+ mile long crevice was seen from space, and nearly stretched from Ontario, Canada, to Cleveland, OH. A social media – drone video (below) captures the fractured ice along Lake Erie.

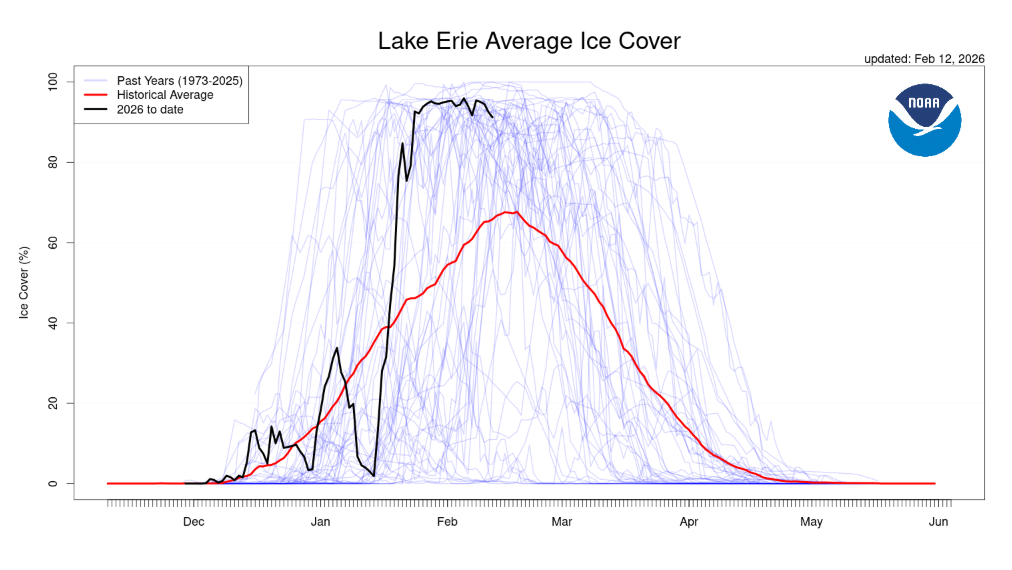

Per NOAA’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (GLERL), ice coverage over Lake Erie was hovering around 95% during early February 2026. Refer to the GLERL graphic that highlights this winter season’s above average ice coverage and how it compares to its historical average.

Using the high refresh rate from the GOES-19 ABI GeoColor, one can see the rapid development of the ice cracking in the middle of Lake Erie on 8 February 2026. The elongated fracture exhibits a northeast to southwest orientation.

GOES -19 ABI GeoColor from ~14-18Z, 8 February 2026

Polar-orbiting satellites also captured the event, where the VIIRS visible (375-m) multi-day animation shows multiple cracks along Lake Erie through 10 February 2026. The lake ice shifts northwestward over the time period.

VIIRS Visible (I-1), 0.64 um, daytime overpasses from 7-10 February 2026

During the last quarter phase of the lunar cycle, nighttime visible imagery observed the reflected moonlight off the lake ice. A VIIRS NCC image comparison shows a before (8 February 2026) and after (9 February 2026) the lake ice started to break up.

VIIRS Near-Constant-Contrast (NCC) nighttime overpasses from 8-9 February 2026

As NWS WFO Cleveland stated below, these type of situations can endanger the general public (e.g., people left stranded on moving ice sheets, ice jams that lead to flooding) and marine vessels that traverse along Lake Erie.

Posted in: Uncategorized, | Comments closed

Mississippi Ice Storm

February 6th, 2026 by Jorel TorresDuring late January 2026, a historic winter storm impacted millions of people across the central and southern United States, producing significant snow, sleet and ice accumulations that led to a flurry of airport delays and cancellations, impassable roadways for motorists, damage to infrastructure, power outages, and cold temperatures. This blog entry focuses on the significant ice (and sleet accumulations) that occurred across Mississippi and adjacent states. The video below captures the devastating impacts in Mississippi, that included widespread downed power lines and trees caused by high amounts of ice accumulation due to freezing rain. Even the University of Mississippi (known as Ole Miss), located in Oxford, MS, was closed for an extensive period of time due to the power outages and travel challenges. Regional snow, sleet and ice accumulation reports can be accessed from the WFO – Jackson, MS and WFO – Memphis, TN webpages.

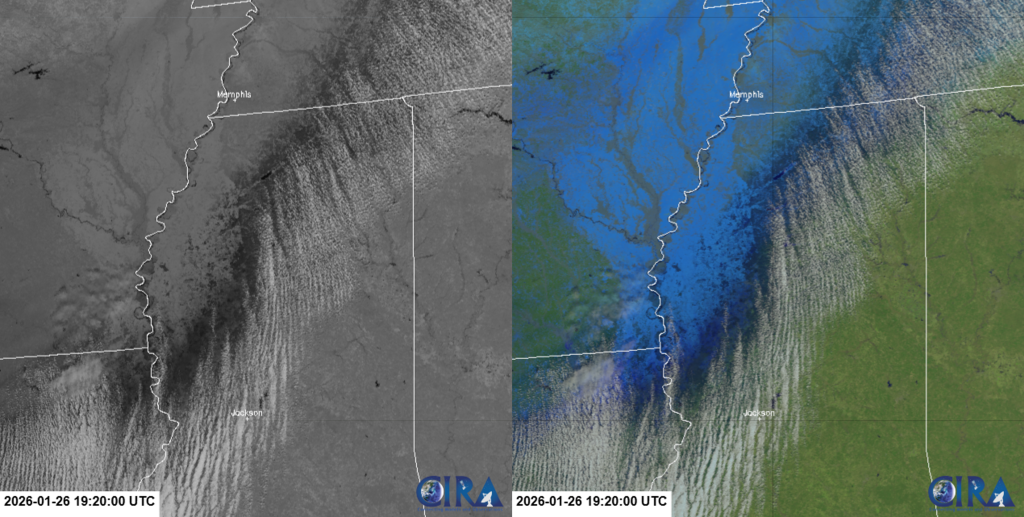

After the storm passed through the region, the SNPP VIIRS Snowmelt RGB provided a large-scale view of the snow (i.e., dry snow, depicted in light blue), sleet or wet snow (dark blue) and ice (darkest blue) accumulations across several southern states.

VIIRS Snowmelt RGB at 1920Z, 26 January 2026

The VIIRS Snowmelt RGB is unique, as it incorporates the VIIRS 1.24 um spectral band within the green spectra of the RGB, and is highly sensitive to snow and ice properties. Additionally, the 1.24 um is not currently available on existing geostationary satellites. A zoomed-in comparison between the 1.24 um and the VIIRS Snowmelt RGB imagery can be seen below. Ice accumulations across the Lower Mississippi River valley stand out in each image and are seen in dark grey/black colors in the 1.24 um imagery and the darkest blue colors within the RGB. Both datasets exhibit 750-m spatial resolutions.

VIIRS 1.24 um (left) and VIIRS Snowmelt RGB (right) at 1920Z, 26 January 2026

This region also experienced numerous power outages. The VIIRS Day/Night Band (DNB) provided a before and after image comparison that shows the emitted city lights that are typically seen across the area, contrasted with the disappearance of city lights after the storm passed through. Notice the significant reduction of emitted city lights (a.k.a., power outages) that can be seen across northeastern Louisiana and rural Mississippi. The impacted areas align with where significant ice accumulations were observed.

VIIRS DNB image comparison: (Before) 28 December 2025 and (After) 27 January 2026

Post storm, a week long VIIRS DNB animation (shown below) observed a few city lights reappearing across the domain. Reflected moonlight also captures snow disappearing and receding towards the north and northwest.

VIIRS DNB: nighttime visible images from 27 January 2026 through 4 February 2026

Posted in: Uncategorized, | Comments closed

Southeastern Australia Bushfires

January 16th, 2026 by Jorel TorresAfter the start of the new year, hot, dry, and windy conditions were conducive to bushfires erupting over southeastern Australia. The fires were primarily observed in the state of Victoria, where the capital city of Melbourne resides. According to the broadcast outlet, 10-News Melbourne, approximately 400,000 hectares (or ~980,000 acres) were burned over the region, as of 14 January 2026. Refer to the social media link below that describes the bushfires and the impacts to the local communities.

The Japan Meteorological Agency’s Advanced Himawari Imager (AHI) captured the fires between 6-11 January 2026. The shortwave infrared imagery from AHI observes the fire hotspots (white and red pixels) at a 2-km spatial resolution, with a 10 minute temporal resolution. Notice, several fires can be spotted across the state of Victoria while multiple rounds of cloud cover and convection pass over the scene.

Himawari-9 AHI 3.9 um from 18Z, 6 January 2026 to 18Z, 11 January 2026

Zooming into the eastern portion of the state of Victoria, a daytime animation from the VIIRS Day Fire RGB shows the initial fire hot spots (red), the rapid fire spread and the corresponding burn scars (reddish brown) during the five-day period. The RGB is sensitive to fire hotspots, vegetation health (e.g., burn scars), and smoke (blue colors) where the RGB’s spectra contains a combination of the 3.7 um, 0.86 um, and the 0.64 um channels. The RGB exhibits a 375-m spatial resolution.

VIIRS Day Fire RGB daytime images from 6 January 2026 to 11 January 2026

During the same timeframe, nighttime visible imagery provided a view of the emitted city lights (individual white pixels or clusters), while also observing the emitted lights produced from the fires (bright, non-uniform white pixels). The VIIRS Near-Constant Contrast (NCC) animation below captures the spread of several fires, moving rapidly toward the south/southeast over the five-day period. Additionally, a distinct, nighttime fire smoke plume can be identified in the imagery on 9 January 2026. A large fire, located in the northeastern part of Victoria, produced a significant smoke plume on its southeast flank, which carried toward the coastline. Southwest of the fires, the emitted lights from Melbourne can be seen along the coastline.

VIIRS NCC nighttime images from 6 January 2026 to 11 January 2026

To help differentiate between the emitted lights from cities, to those from fires, users can compare the VIIRS NCC with the VIIRS shortwave infrared imagery. Refer to the imagery animation below. Emitted lights from fires have corresponding thermal hotspots (i.e., black pixels, seen in the VIIRS 3.7 um), while emitted lights that do not have a corresponding thermal signature in the shortwave infrared can be inferred as city or town lights.

VIIRS NCC and VIIRS 3.7 um (I-4) Band at 1533Z, 9 January 2026

Posted in: Uncategorized, | Comments closed

Hawaii – The Big Island’s Winter Wonderland

January 9th, 2026 by Jorel TorresEarlier this week, the Big Island of Hawaii received snow over the volcanic summits of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. Both summits are 13,000 plus feet above sea level, where they can accumulate snowfall, typically throughout Hawaii’s wet season (October through April). On Monday, 5 January 2026, winter storm warnings forecasted high winds and 5-10 inches of snowfall along the higher elevations of the Big Island of Hawaii. Pictures of the snow peaks can be viewed here, while the United States Geological Survey (USGS) provides a video (below) that captures the snowy summit of Mauna Loa.

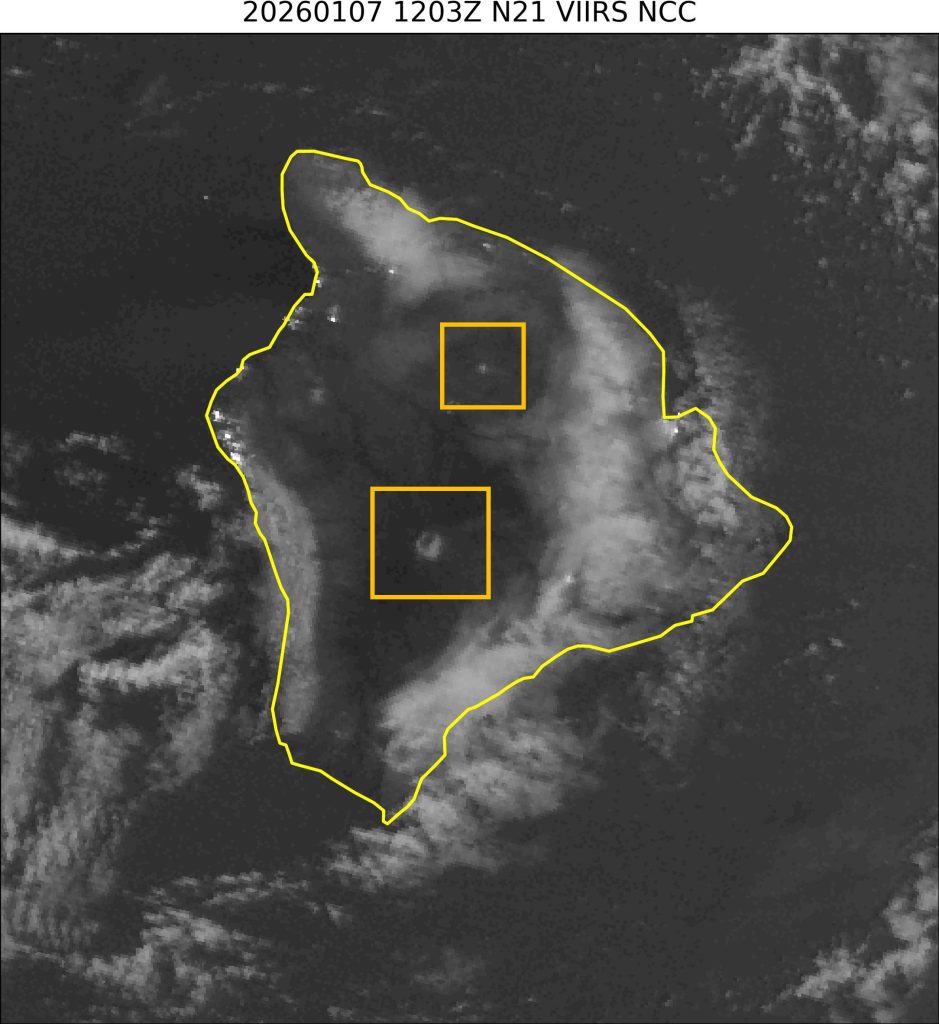

Nighttime visible imagery from NOAA-21 VIIRS captured the snow cover over the peaks on 7 January 2026. Refer to the orange boxes in the imagery. Moonlight illuminates the snow cover while a mix of clouds and emitted city lights are seen scattered across the island.

VIIRS NCC at 1203Z, 7 January 2026

Later that afternoon, remnant snow cover can be viewed by the VIIRS Day Cloud Phase Distinction RGB, that observes the snow in green pixels (seen within the orange boxes) at 375-m spatial resolution.

VIIRS DCPD RGB from 2313Z-2343Z, 7 January 2026

Posted in: Uncategorized, | Comments closed