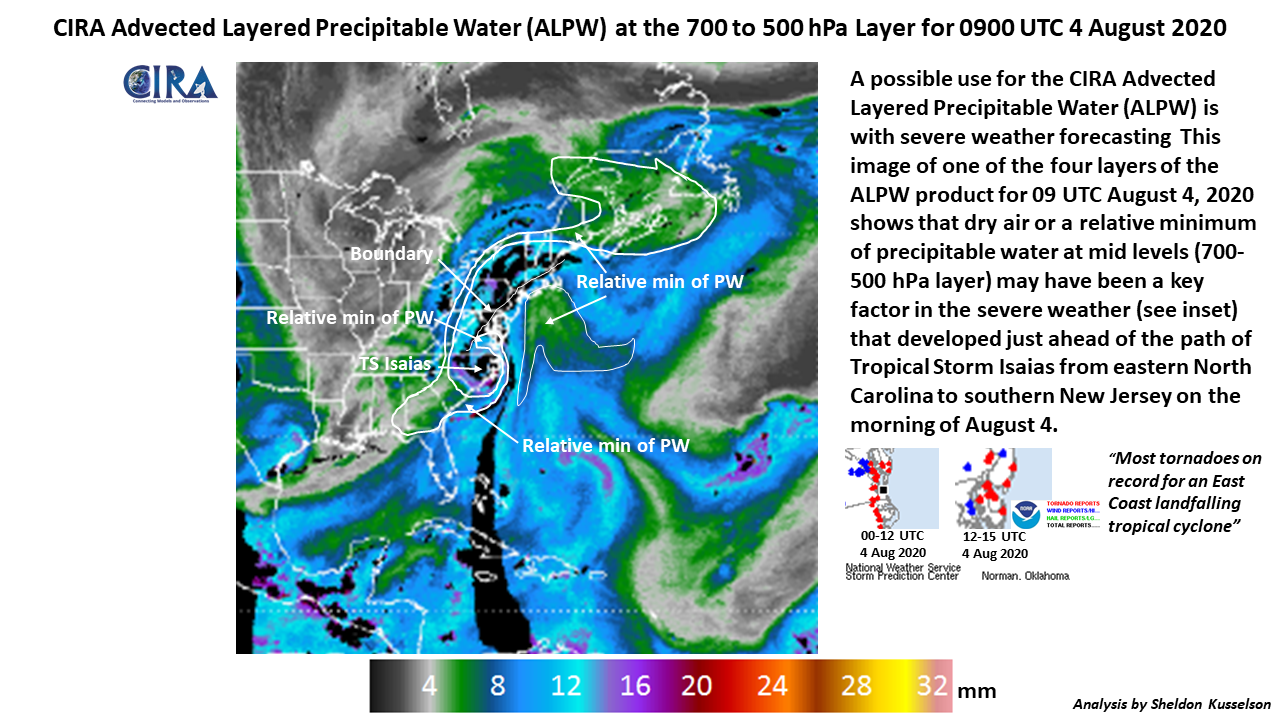

ALPW depiction of mid-level dry air associated with Tropical Storm Isaias

August 21st, 2020 by Dan BikosBy Sheldon Kusselson

Loop of ALPW 700-500 mb layer over a long time period

Posted in: Severe Weather, Tornadoes, Tropical Cyclones, | Comments closed

Impacts of Water Vapor on Satellite Dust Detection of the 16-17 February 2020 Saharan Air Layer Dust Event over the Eastern Atlantic

August 4th, 2020 by Dan BikosLewis Grasso1, Dan Bikos1, Jorel Torres1, John Forsythe1, Heather Q. Cronk1, Curtis J. Seaman1, Emily Berndt2

1Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO

2NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Short-term Prediction Research and Transition Center, Huntsville, AL

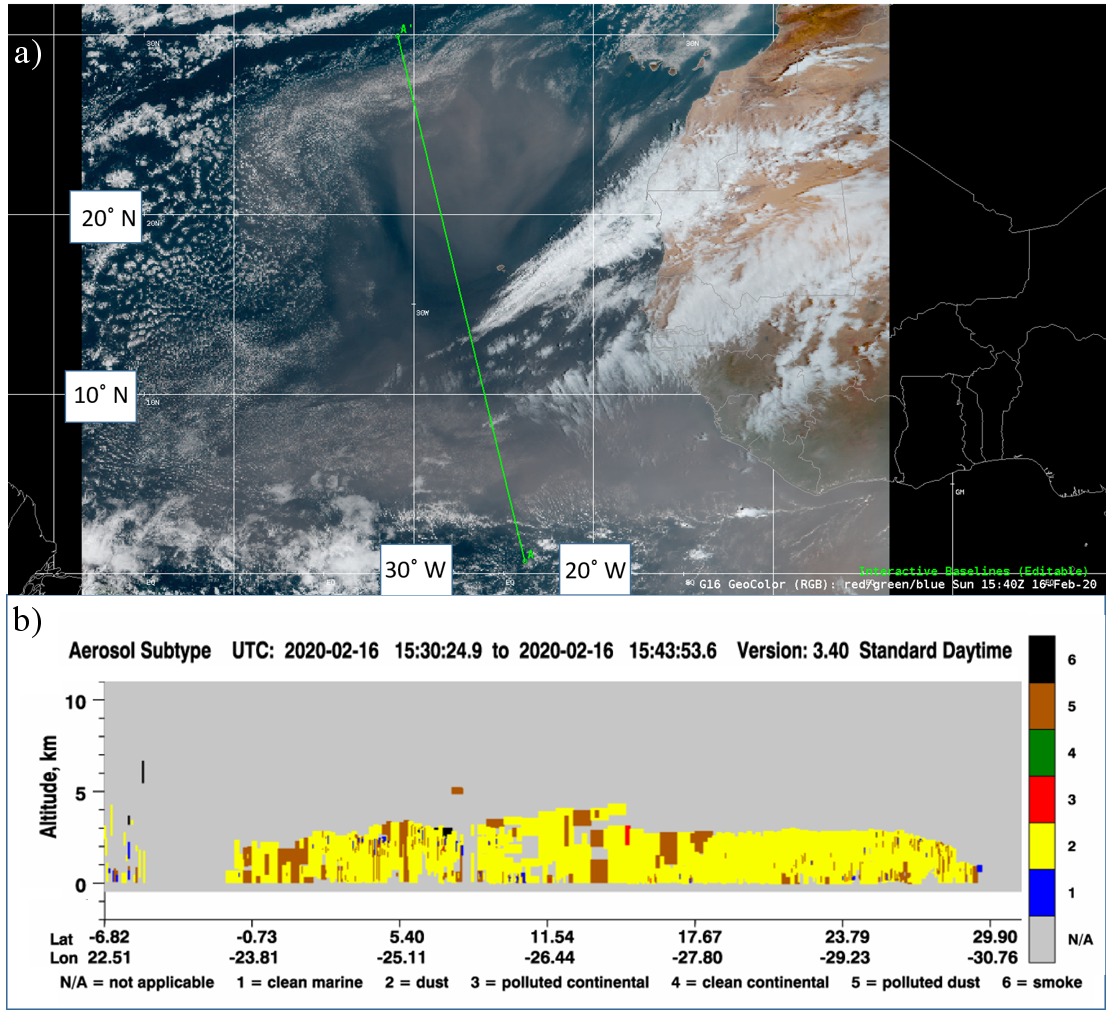

In the afternoon of 16 February 2020 a dust layer moved off western Africa. A loop of GeoColor imagery from ABI on GOES-16 exhibits the dust layer, which is typically part of a Saharan Air Layer (SAL), that moved westward over the eastern Atlantic Ocean. At approximately 15:40 UTC 16 February 2020, CALIPSO moved northward over the SAL; a green line segment in Fig. 1a indicates the ground track of the CALIPSO satellite. Data from CALIOP, the primary sensor onboard CALIPSO, was used to produce a Vertical Feature Mask (VFM), also shown in Fig. 1b. As seen in the VFM, the primary constituent was dust and is indicated in the VFM as a yellow shading, from the surface to about 3.0 km.

Figure 1: (a) GeoColor imagery diagnosed from ABI on GOES-16 valid at 1540 UTC 16 February 2020 along with a portion of the ground track (green line segment) of CALIPSO from 1530 UTC to 1543 UTC 16 February 2020. (b) Dust, in yellow, is displayed in the vertical feature mask from CALIOP.

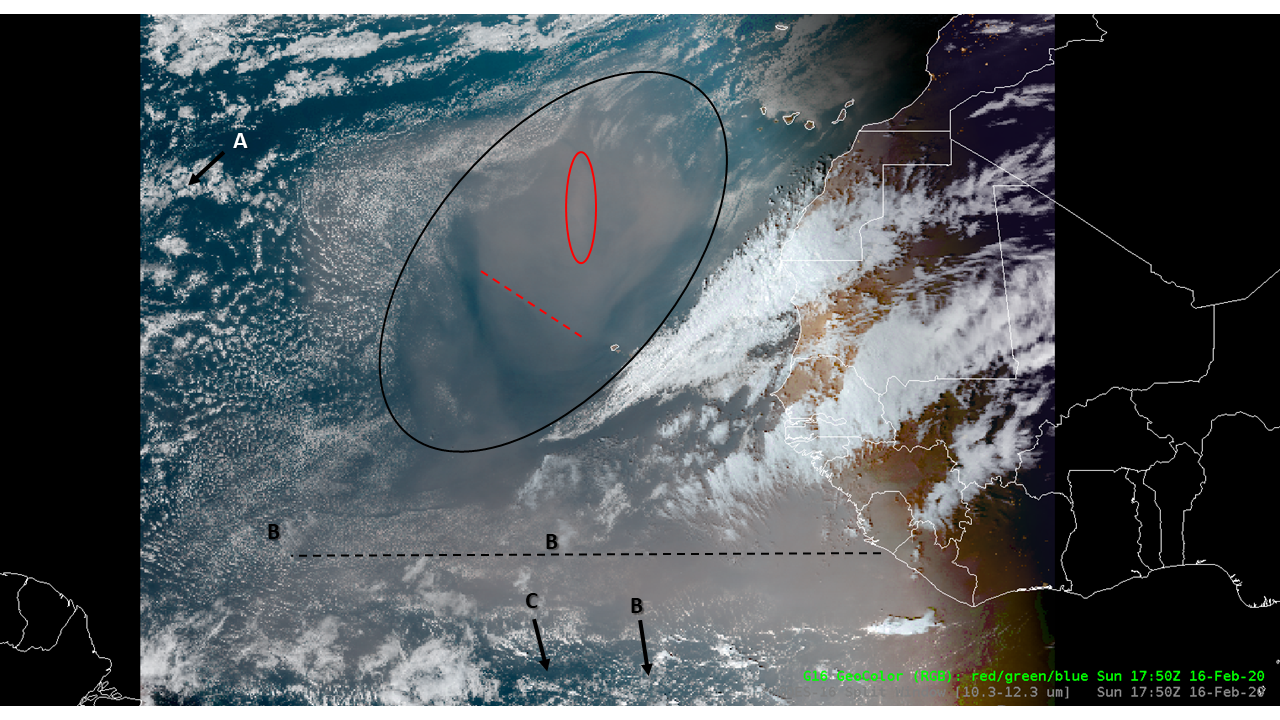

Annotations are placed on GeoColor imagery valid 17:50 UTC 16 February 2020 that distinguish between a northern dust region (NDR) and a southern dust region (SDR), see Fig. 2. A black oval is used to indicate the NDR while a horizontal, black, dashed line segment denotes the SDR in the figure.

Figure 2: GeoColor imagery diagnosed from ABI on GOES-16, valid 1750 UTC 16 February 2020, along with the following annotations: A black oval bounds dust in the NDR while the horizontal, black, dashed line highlights dust in the SDR. Within the black oval are additional annotations in red. Further the letters A (upper left portion of the figure), B, and C appear. All annotations are used for comparison purposes with Fig. 3.

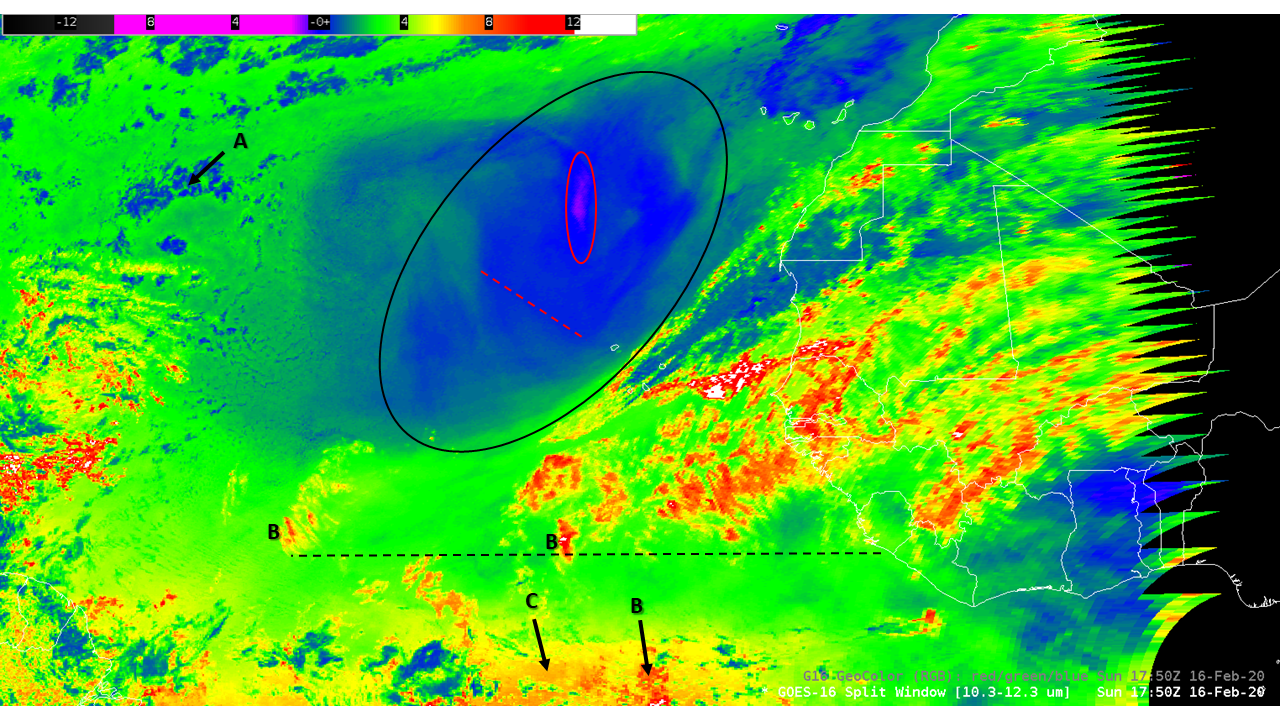

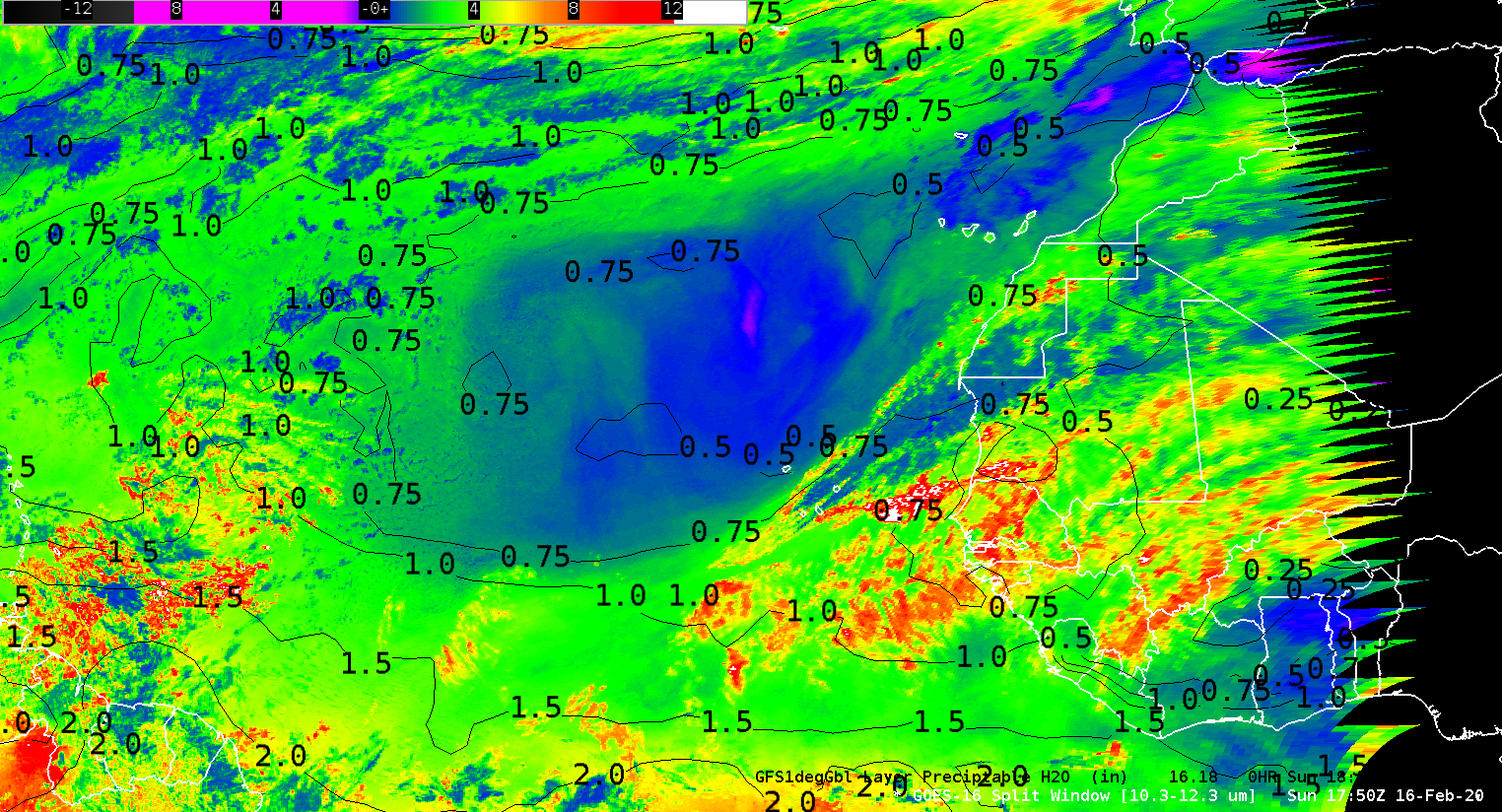

A companion image to Fig. 2 is Fig. 3, which displays the ABI infrared channel difference, Tb(10.35 um) – Tb(12.3 um)

Figure 3: Channel difference, Tb(10.35 µm) – Tb(12.3 µm) (˚C), from ABI on GOES-16 valid at 1750 UTC 16 February 2020. Annotations are the same as in Fig. 2. Dust is indicated by the blue and purple colors within the black oval in the northern dust region. There was a lack of a dust signal in the southern dust region.

A dust signal is evident in the NDR with negative to near zero values of the channel difference. In sharp contrast, the SDR is void of a dust signal with values of the channel difference near 3˚C in Fig. 3. In addition, the red oval in Fig. 2 surrounds thick dust, which is coincident with a strong dust signal in Fig 3. Southwest of the red dashed contour in Fig. 2, dust appears thin, which was a region with a weak dust signal in Fig. 3. In the northwest portion of Figs. 2 and 3 the letter A is used to highlight the sharp boundary of low-level liquid clouds as opposed to the diffuse boundary of dust, despite the same channel difference color. That is, different features in Fig. 2 may have similar values of the channel difference in Fig. 3. Further, the letter B denotes locations of thin cirrus along the western portions of the horizontal, black, dashed line segment of the SDR. Although the letter C identifies a region with a similar channel difference color as thin cirrus in Fig. 3, a comparison of the region C in Figs. 2 and 3 reveal clear skies.

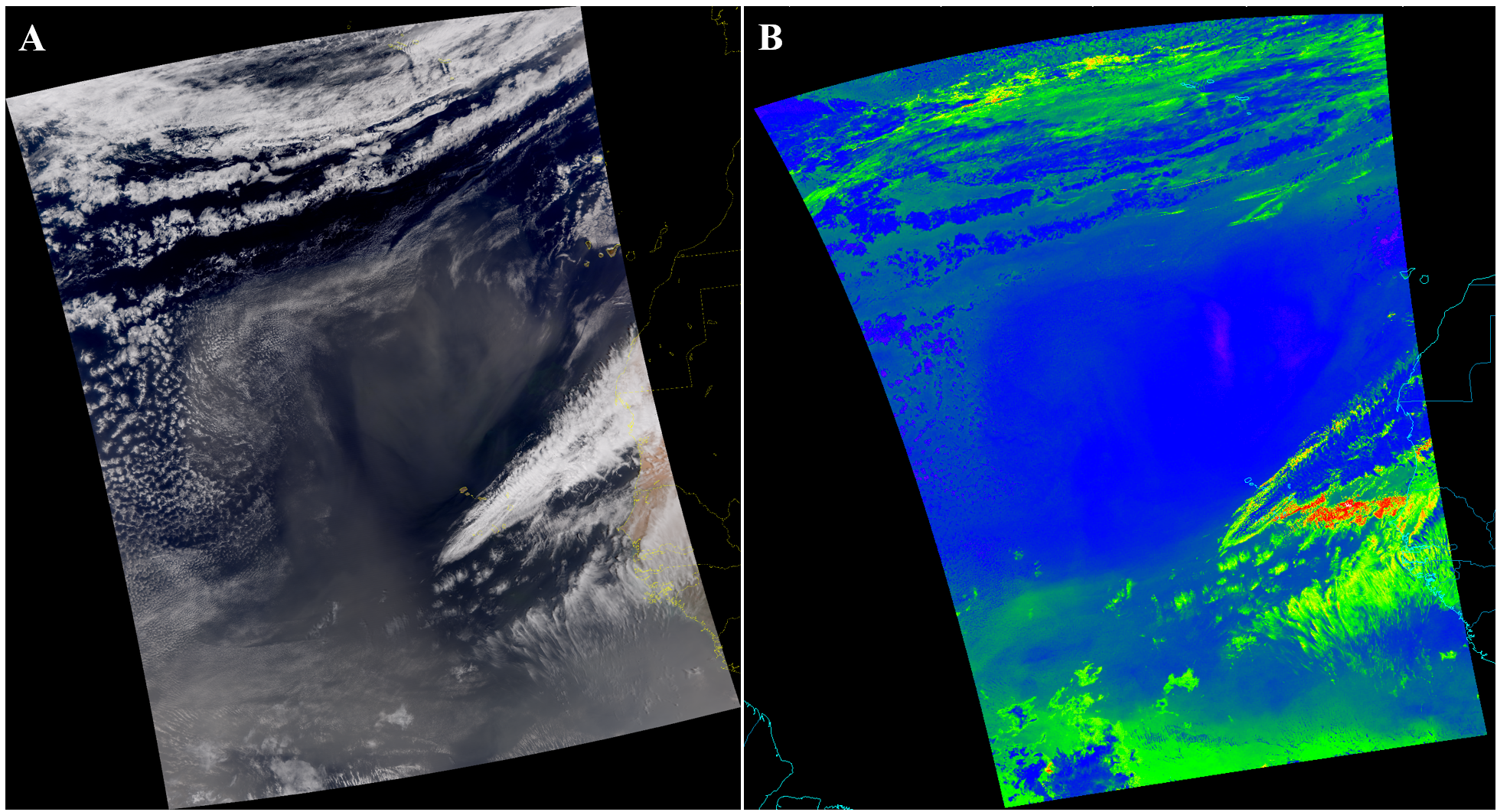

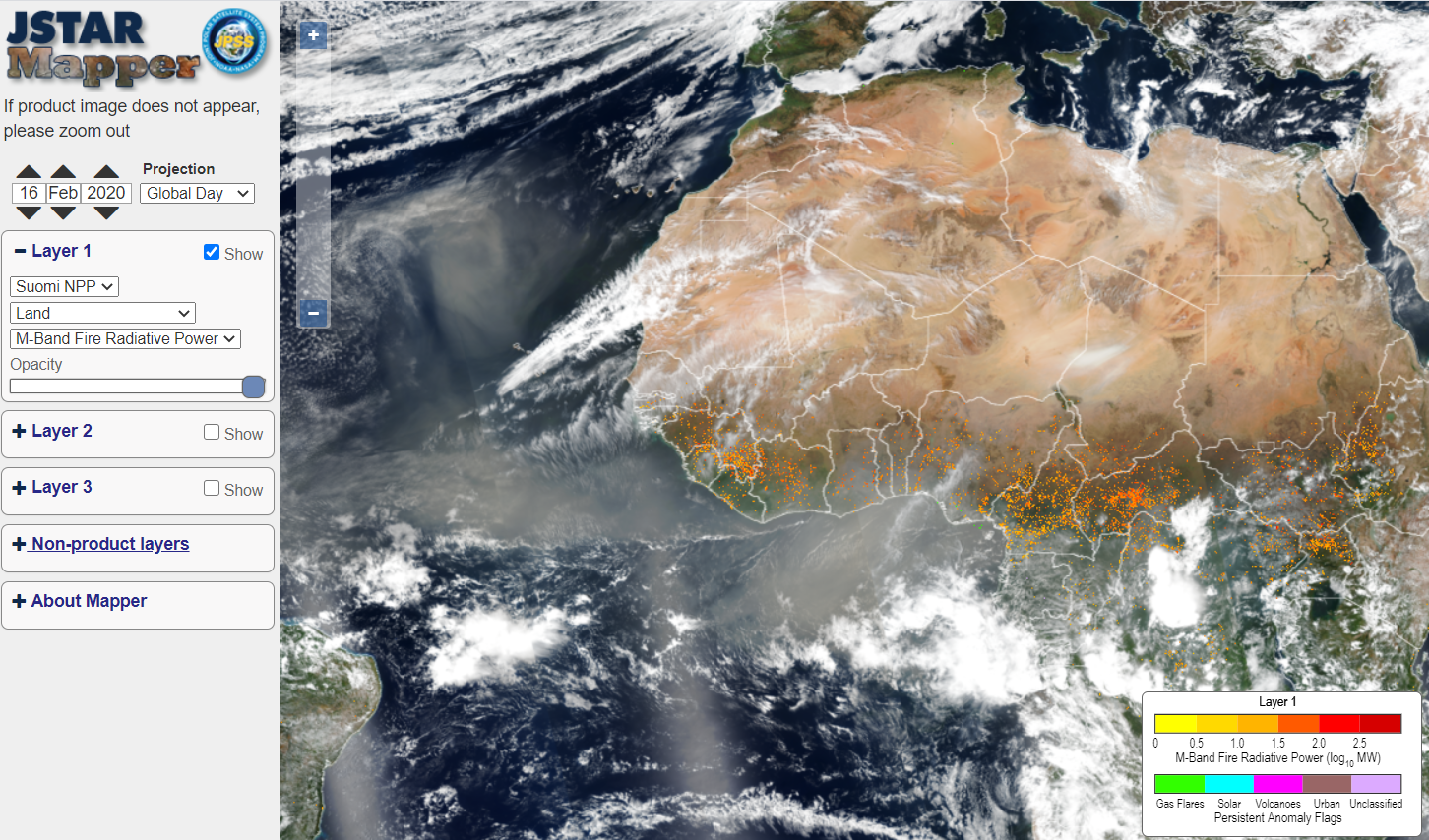

Imagery from VIIRS on NOAA-20 at 1510 UTC 16 February 2020 is displayed in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Data from VIIRS on NOAA-20 valid at approximately 1510 UTC 16 February 2020 showing (a) True-Color, as opposed to GOES-16 ABI GeoColor, imagery and (b) VIIRS channel difference, Tb(10.76 µm) – Tb(12.01 µm), with the same color table shown in Fig. 3.

Note the similarity of patterns in True-Color imagery from VIIRS (Fig. 4a) and the channel difference (Fig. 4b) compared to those from ABI in Figs. 2 and 3. One unanswered question is why does dust in the NDR and SDR (Fig. 2) have such a different appearance in the channel difference (Fig. 3).

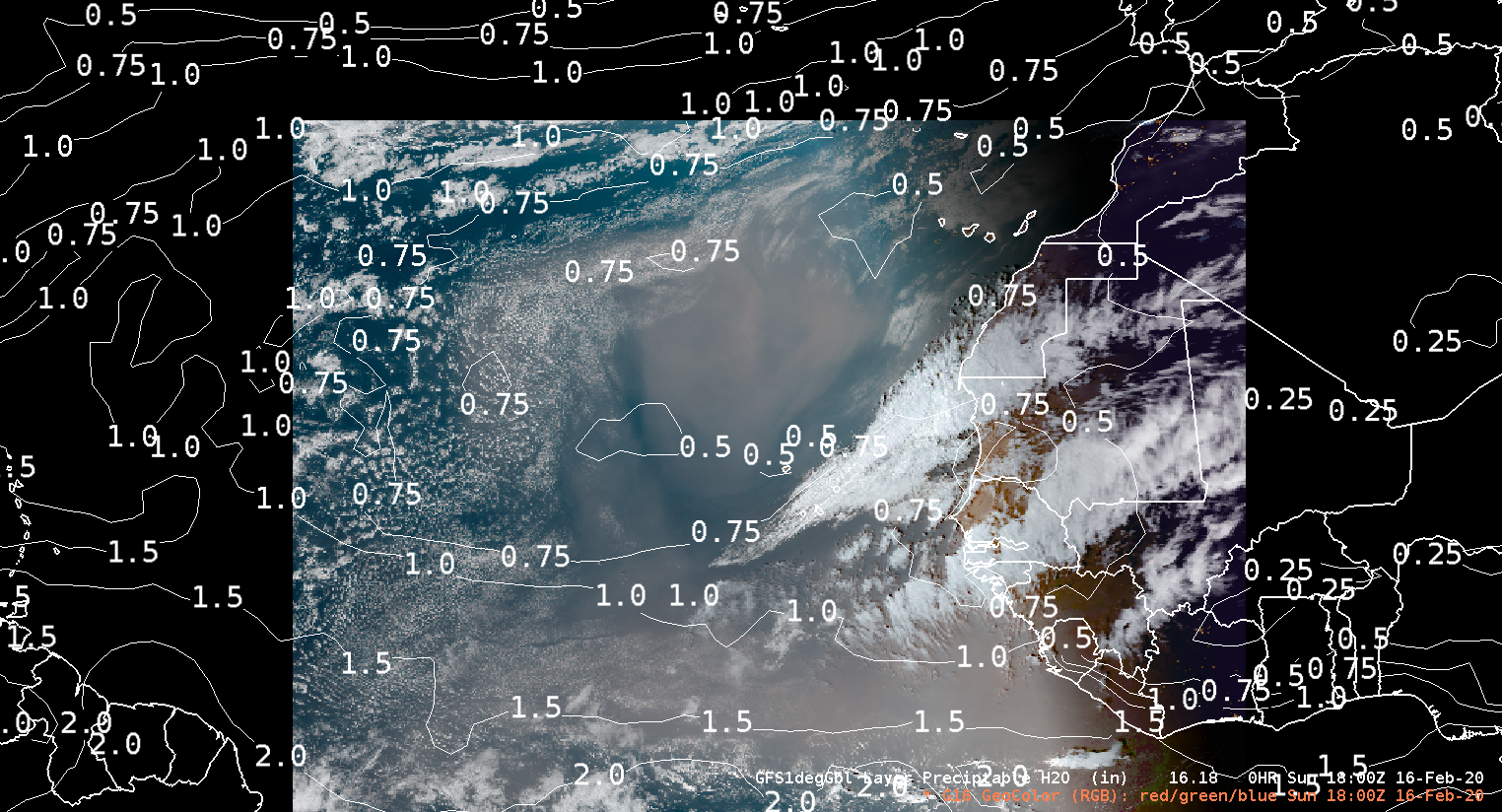

Values of the total precipitable water (TPW) from the GFS analysis are superimposed on GeoColor imagery, both valid at 1800 UTC 16 February 2020 (Fig. 5). As illustrated in the figure, values of TPW varied between 0.5 inches to 0.75 inches in the NDR; in contrast, TPW values increased significantly to near 1.5 inches in the SDR.

Figure 5: TPW (in) from the GFS analysis plotted on a GeoColor image derived from GOES-16 ABI; all data is valid at 1800 UTC 16 February 2020.

Values of the TPW from the GFS analysis were also superimposed on the ABI channel difference (Fig. 6), valid at the same time as Fig. 5.

Figure 6: Same as Fig. 5, except TPW (in) is plotted on the GOES-16 ABI Tb(10.35 µm) – Tb(12.3 µm) channel difference (˚C).

One striking feature in Fig. 6 is the clear link between low values of TPW (0.5-075 inches) and a dust signal in the NDR as opposed to high values of TPW (1.0-2.0 inches) an a lack of a dust signal in the SDR.

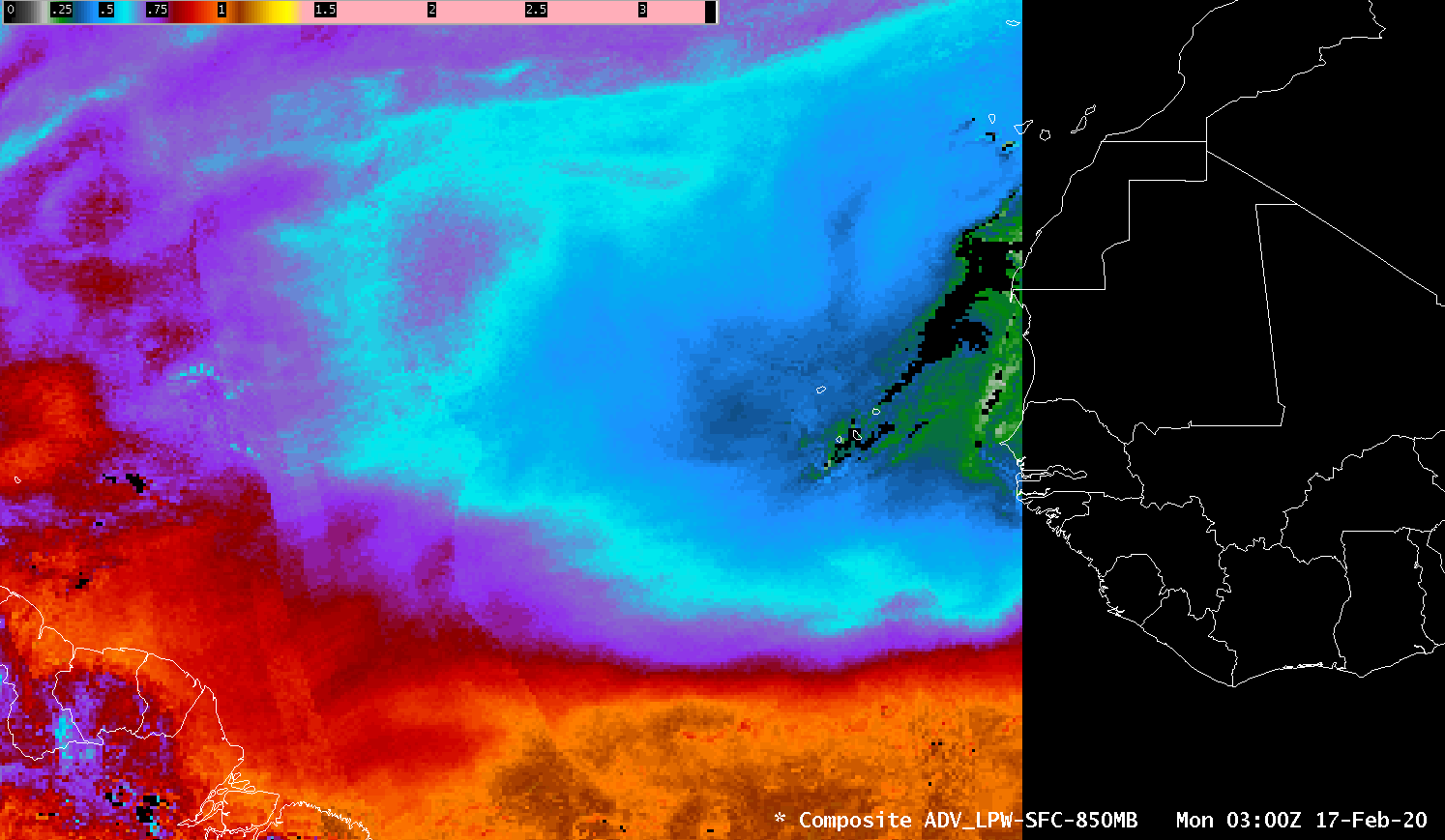

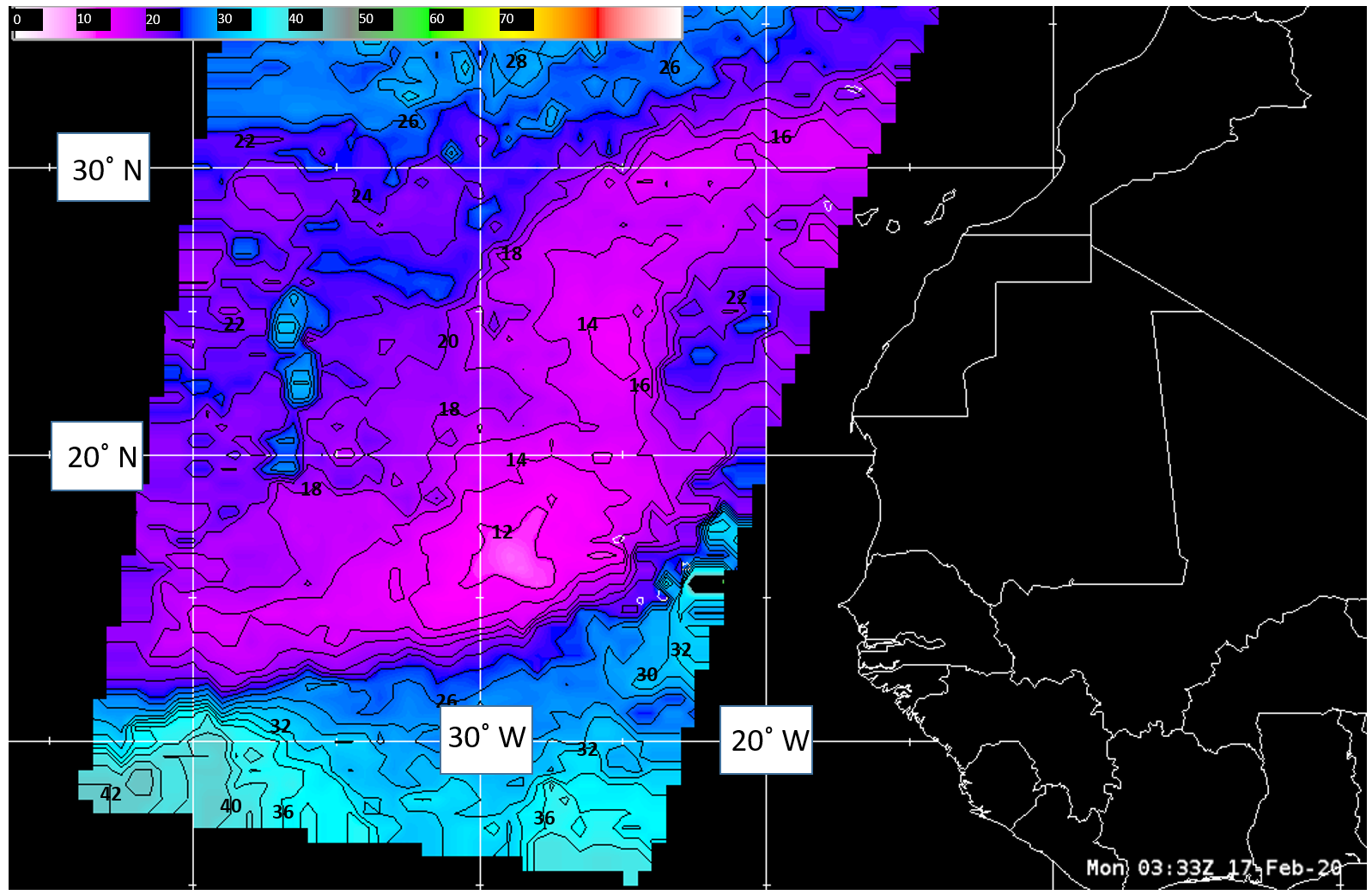

Satellite retrievals of Advected Layer Precipitable Water (ALPW) retrieved from microwave instruments, valid 0300 UTC 17 February 2020, are displayed in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Advected Layer Precipitable Water product (in) for the surface to 850 hPa layer valid at 0300 UTC 17 February 2020.

As seen in the figure, the NDR was characterized has having the lowest values of LPW, from the surface to 850 hPa. Values increased sharply in the SDR where a dust signal was absent in ABI channel difference images.

Values of TPW diagnosed or computed from retrieved NUCAPS soundings, valid 03:30 17 February 2020, are shown in Fig. 8. Similar to the patterns in Fig. 7, values of TPW were the lowest over the NDR and largest over the SDR.

Figure 8: Gridded NUCAPS TPW (mm) valid at 0333 UTC 17 February 2020, which represents the time of the granule in the image.

Observations of the water vapor field for this dust event allows for the development of a hypothesis. Based on GFS analysis and satellite retrievals of water vapor, dust is detected/masked when water vapor content in the atmosphere is low/high. That is, when water vapor values are low enough infrared channel differences, and dust products, will detect a dust signal. However, when water vapor content is above a critical value the channel difference will be dominated by a water vapor signal, thus masking dust.

One beneficial consequence of infrared channel differencing of dust in a dry environment is the ability to track dust layers when the sun sets. During the night, GeoColor imagery will be unable to reveal dust layers as a result of the loss of reflection of solar energy off dust. Figure 9 is an animation of the channel difference, which allows a forecaster to follow the nocturnal morphology of dust.

Moisture products for the tornadic storm of 4 July 2020 in Saskatchewan

July 10th, 2020 by Dan BikosOn 4 July 2020 a thunderstorm developed in southern Saskatchewan that led to numerous tornadoes (video, picture, pictures).

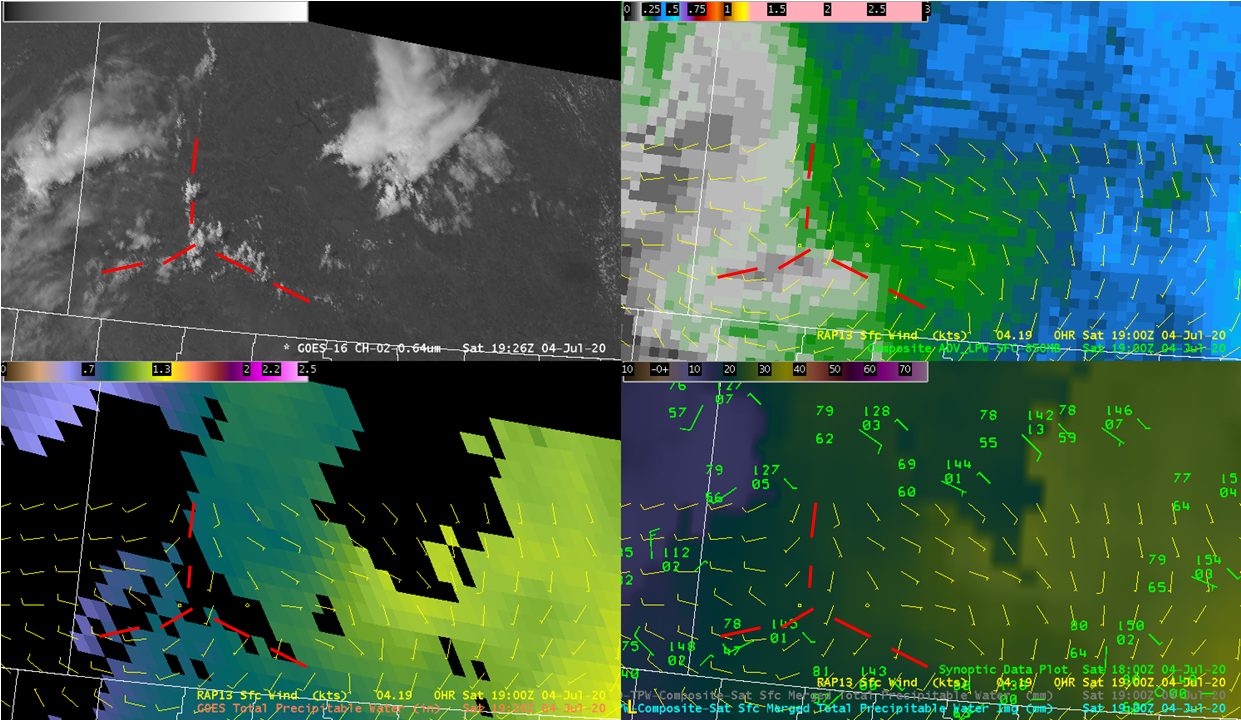

Let’s analyze various satellite derived moisture products in the time period leading up to the tornadic storm. The following loop 4-panel loop:

Upper-left: GOES-16 visible (0.64 micron) imagery.

Upper-right: Advected Layer Precipitable Water (ALPW) product in the surface to 850 mb layer with RAP 00hr surface winds.

Lower-left: GOES-R baseline Total Precipitable Water (TPW) product with RAP 00hr surface winds.

Lower-right: Merged (GOES + POES) Advected TPW product with surface observations.

It’s important to note the status of the 3 moisture products. The GOES-R baseline TPW product has been operational in AWIPS, the ALPW product is non-operational but will become operational in AWIPS within the next 1-2 years, while the Merged Advected TPW product is very much experimental (still in development).

First looking at the visible imagery, we observe morning convection while later we see storms develop along a north-south oriented boundary. Most of the storms move off to the northeast, however one of the storms appears to develop at the intersection of this boundary with another boundary that is almost east-west oriented and this storm moves southeast. Tornadoes are associated with the storm as it’s moving southeast and exhibits inflow feeder clouds.

The RAP surface winds and surface observations provide indications of a triple point, however the signal is not strong since the winds are not strong. If we use this data along with indications of the boundary in the visible imagery to annotate with red dashed lines where the boundaries are:

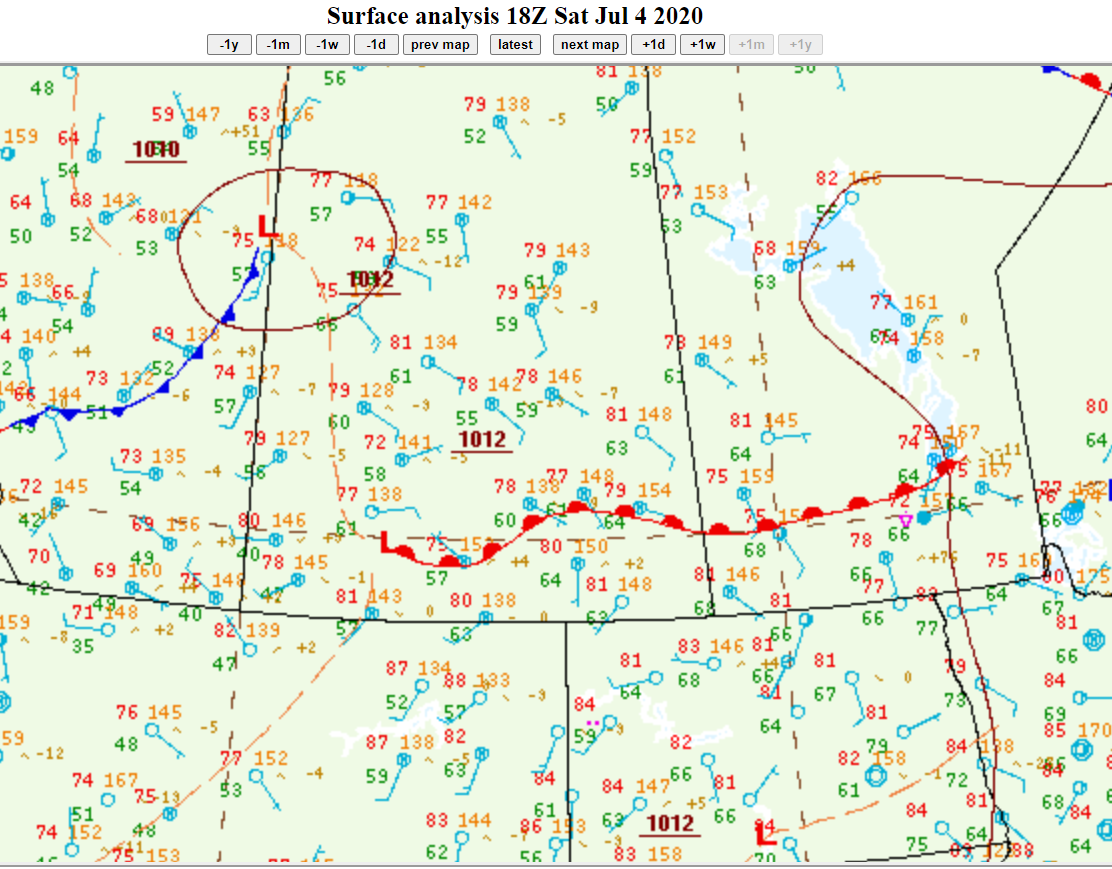

The triple point shows up nicely with west winds (shortly later northwest winds) with the cold front to the west, light east/southeast winds in the warm sector and southwest winds further south with drier air (78/47 in the observation) – a classic dryline/cold front triple point although in this case much more subtle since the winds were relatively light and the boundaries and air mass differences were subtle (i.e., the weak cold front may be analyzed as a trough). The WPC official surface analysis at 18Z shows the triple point analyzed as a trough to the north and southwest, with a warm front to the east:

Note the color table and range for the bottom 2 panels of the 4 panel image above are corresponding so as to make comparison between the 2 products. One limitation of this however is that gradients at key ranges for this particular case may be smoothed out. An alternative would be a different color table that shows increased contrast across the feature of interest so that it stands out more readily such as this animation depicts:

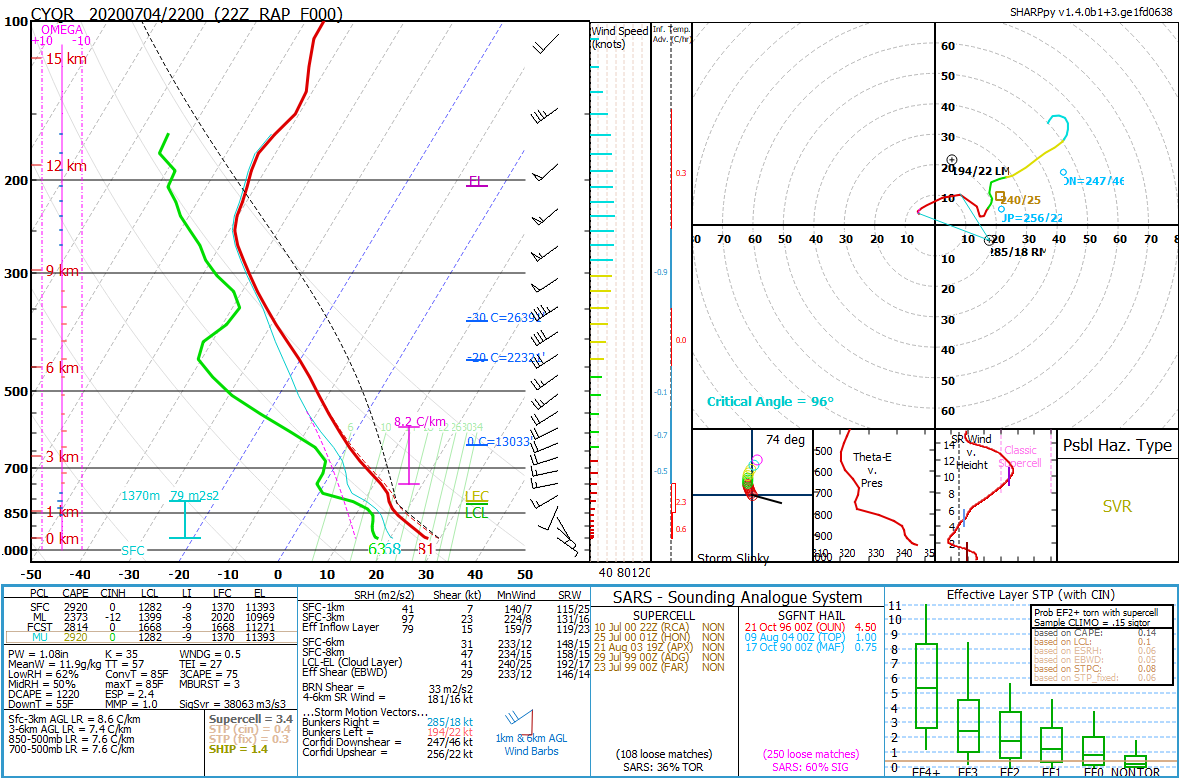

Viewing the animation of the moisture products to focus on the dryline (the analyzed trough extending southwest of the surface low), the TPW products show subtle indications of the relatively drier versus relatively more moist airmasses. However, in comparison with the ALPW surface to 850 mb layer we see that the ALPW product really shines at highlighting the various airmass differences. This shouldn’t be surprising since low-level moisture is key for severe thunderstorms, particularly in an environment with an elevated mixed layer as seen in the RAP 2200 UTC 00hr profile from Regina, SK:

Keep in mind that the ALPW product has 4 layers, and they may be viewed for this case here:

2 key points from this loop:

1) The triple point is very much a low-level feature, it only shows up in a more subtle way in the 850-700 mb layer and does not show up above that.

2) There is rich /deep moisture in the warm sector east of the triple point in a relatively narrow corridor and the storm moves towards this region as it turns to the right (moving southeast in an environment of southwest flow aloft).

One final question worth considering, did the morning convection produce an outflow boundary that moved southwest and contributed to higher moisture / convergence for the afternoon thunderstorms? There are some indications of that in the moisture products with varying degrees of subtlety. The GOES-R baseline product seems to show some increase in TPW to the southwest of the morning convection, while the ALPW seems to show some increase in low-level moisture as well. The following animation supports this hypothesis if we make some continuity assumptions of where the weak outflow boundary would exist, but the key is that it may have reinforced the weak warm front:

Note the inflow feeder clouds towards the end of the animation, a satellite storm-scale signature that indicates the storm is likely severe.

In summary, we have a triple point pattern that led to a tornadic storm. often times we think of a triple point pattern with strong convergence along the boundaries and obvious air mass differences, making identification of the triple point pattern relatively easy. In this case, the winds are much weaker and the boundaries and air mass differences are much more subtle. It’s definitely more challenging to identify this pattern in these circumstances, however ALPW and other moisture products help with respect to identification of air mass differences and boundaries (from the PW gradients).

When using the moisture products operationally, latency should be kept in mind. Let’s first discuss latency as defined as receipt time on AWIPS. The GOES-R baseline TPW product has the least latency (~15 minutes) with ALPW latency a little over 45 minutes while the merged TPW product is about the same albeit still experimental. These products can be used for relatively short-fuse type of events, so long as it’s not so short that latency becomes an issue. Keep in mind, the products that contain POES data have a “hidden latency” in that the most recent passes that are advected to make the products are generally 2 to 6 hours old. Despite these limitations, the evolution of the triple point is captured quite well in the surface to 850 mb layer ALPW. Perhaps the GOES product may have shown this as well, however we have the limitation of cloud obscuration and it is a total precipitable water product. Some of the important changes that occur at lower-levels (therefore captured by the lowest layer ALPW) are “washed out” in a TPW product.

Posted in: Convection, Severe Weather, Tornadoes, | Comments closed

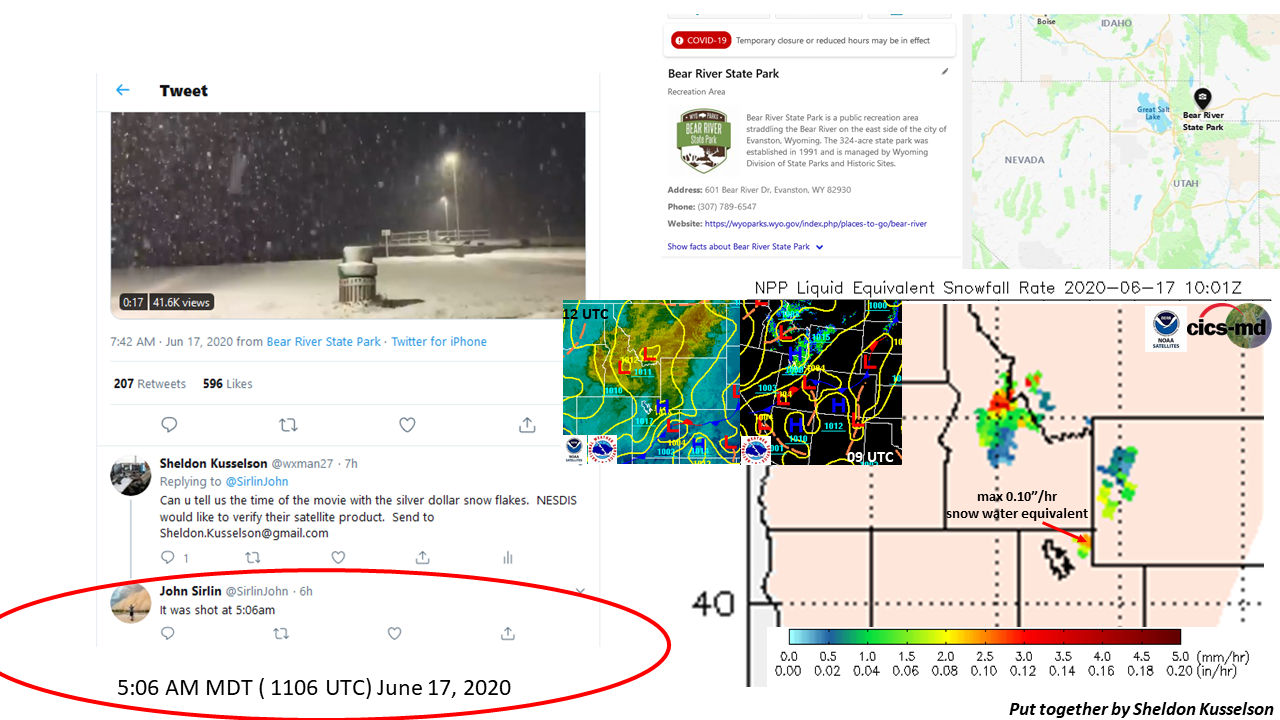

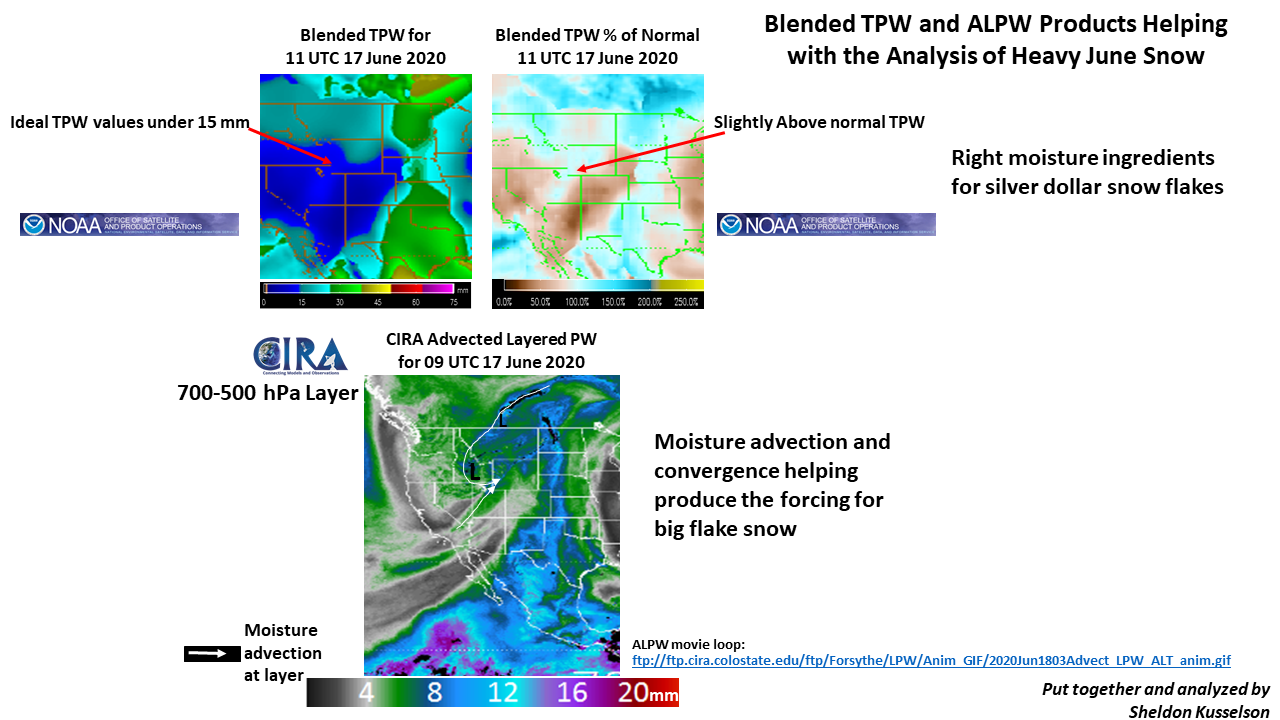

Analysis of June 17, 2020 Wyoming Snow event with JPSS products

June 23rd, 2020 by Dan BikosBy Sheldon Kusselson

ftp://ftp.cira.colostate.edu/ftp/Forsythe/LPW/Anim_GIF/2020Jun1803Advect_LPW_ALT_anim.gif

Posted in: Hydrology, Winter Weather, | Comments closed

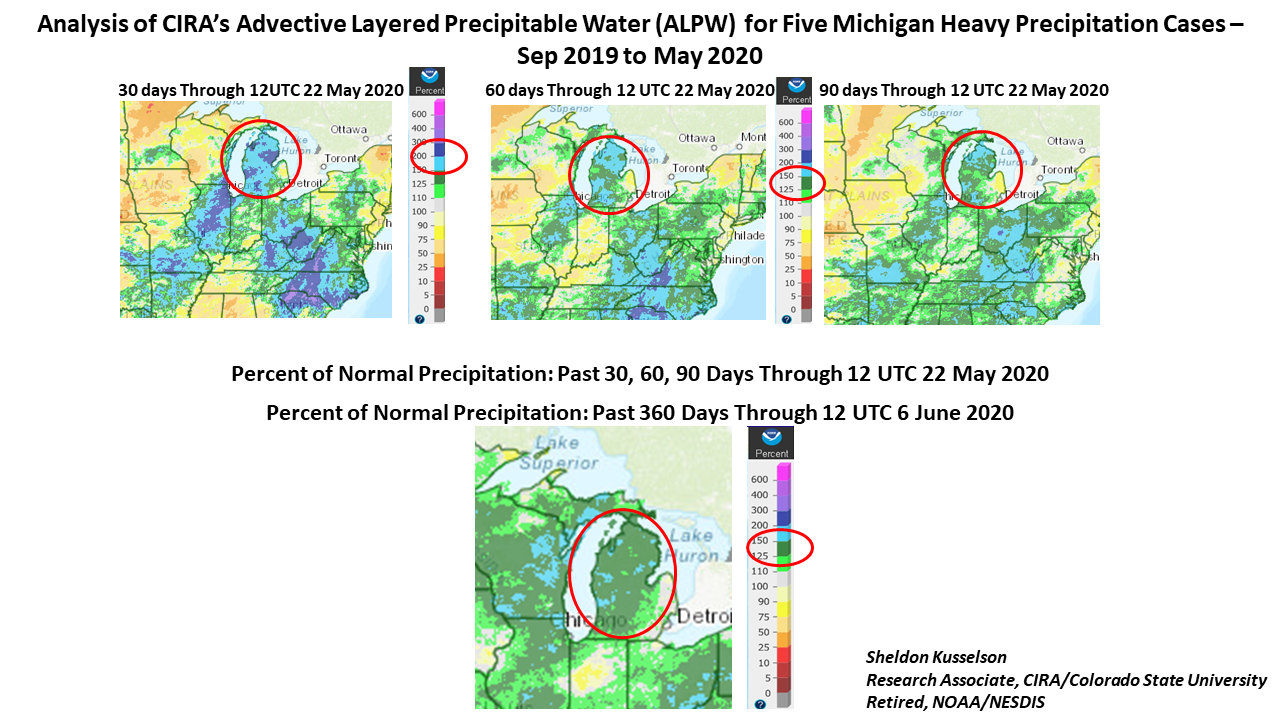

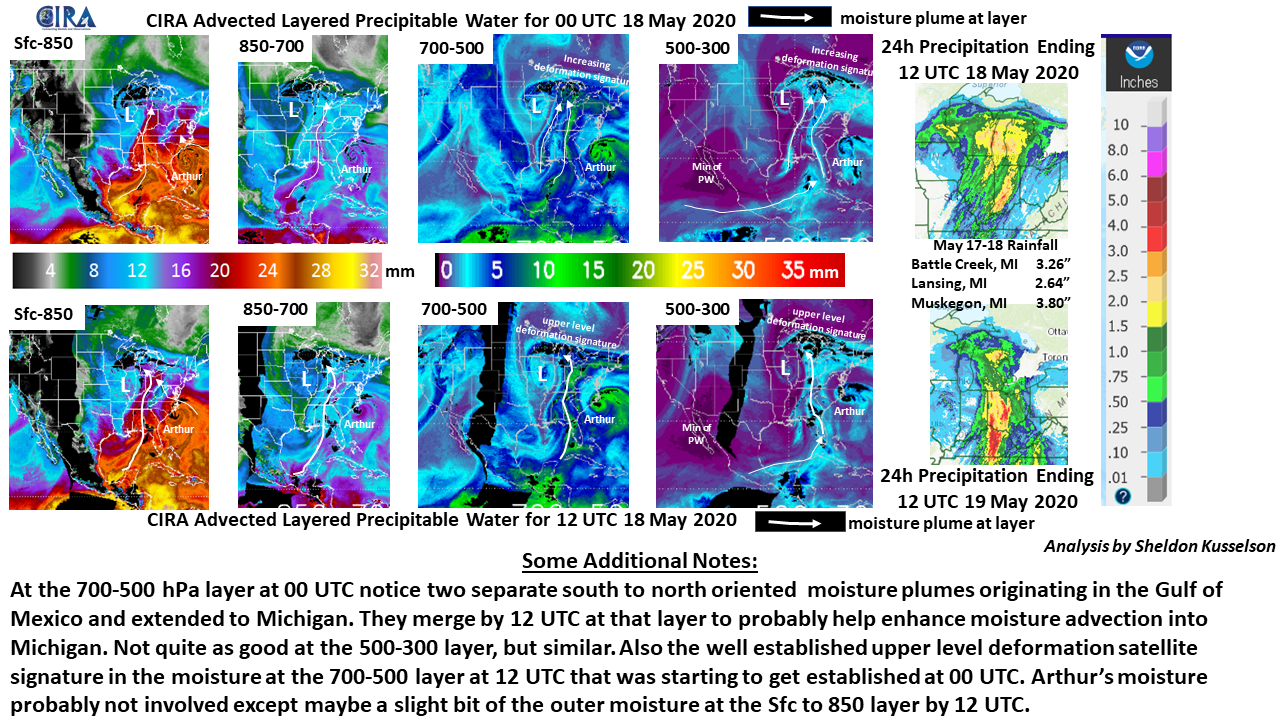

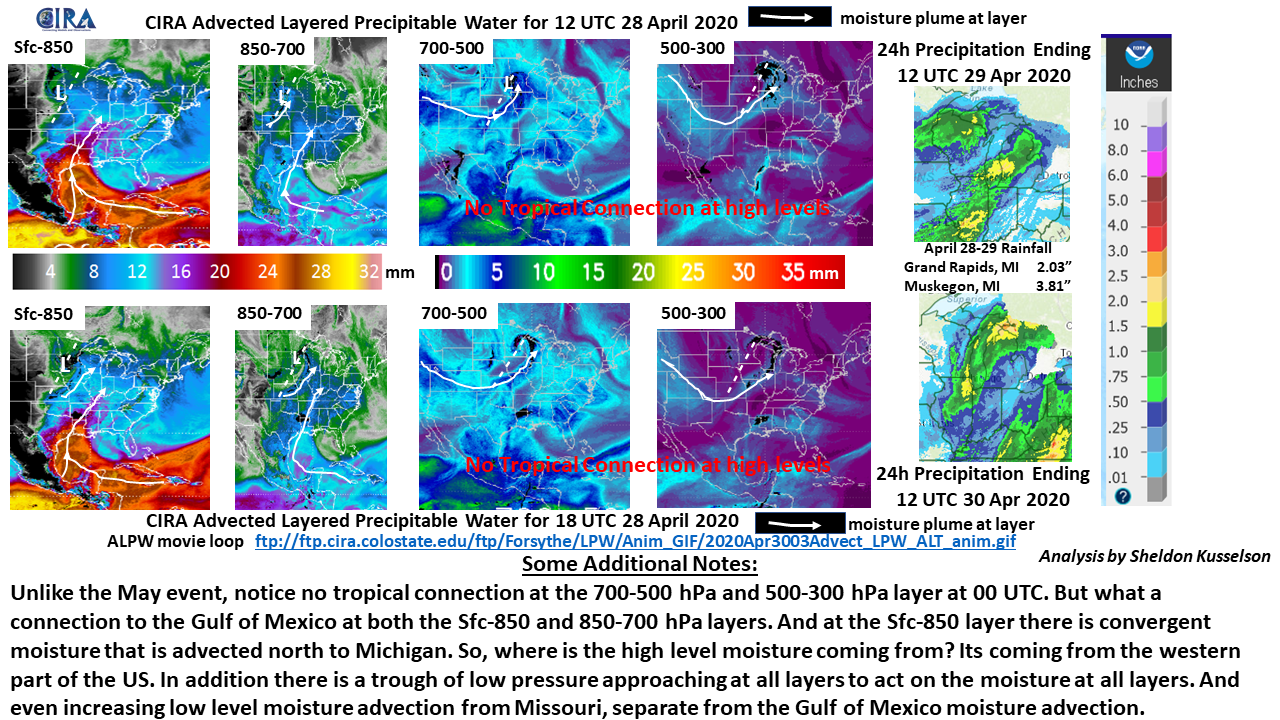

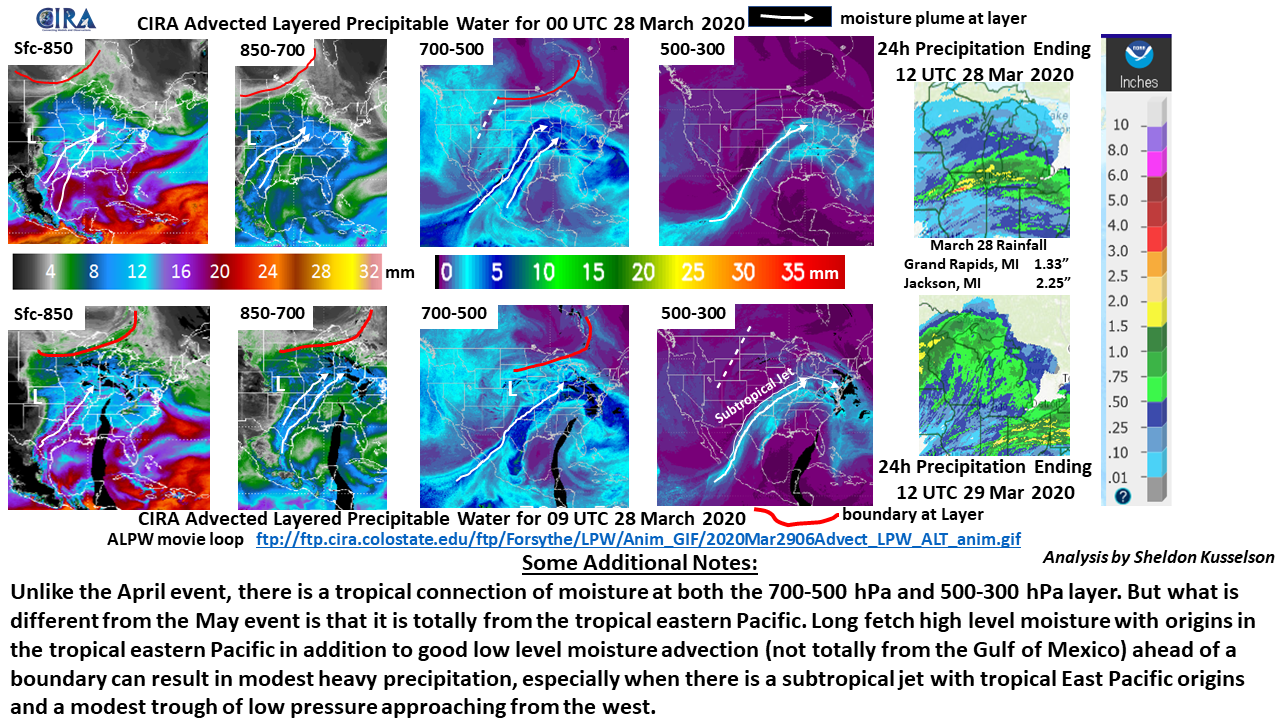

May 2020 flooding in central Michigan

June 9th, 2020 by Dan BikosThis blog entry by Sheldon Kusselson summarizes satellite moisture imagery and products leading to the flood event over central Michigan on 18 May 2020. Comparison with previous events are included.

Animation of ALPW every 3 hours from 03 UTC 18 May to 09 UTC 19 May 2020:

ftp://ftp.cira.colostate.edu/ftp/Forsythe/LPW/Anim_GIF/2020Apr3003Advect_LPW_ALT_anim.gif

ftp://ftp.cira.colostate.edu/ftp/Forsythe/LPW/Anim_GIF/2020Mar2906Advect_LPW_ALT_anim.gif

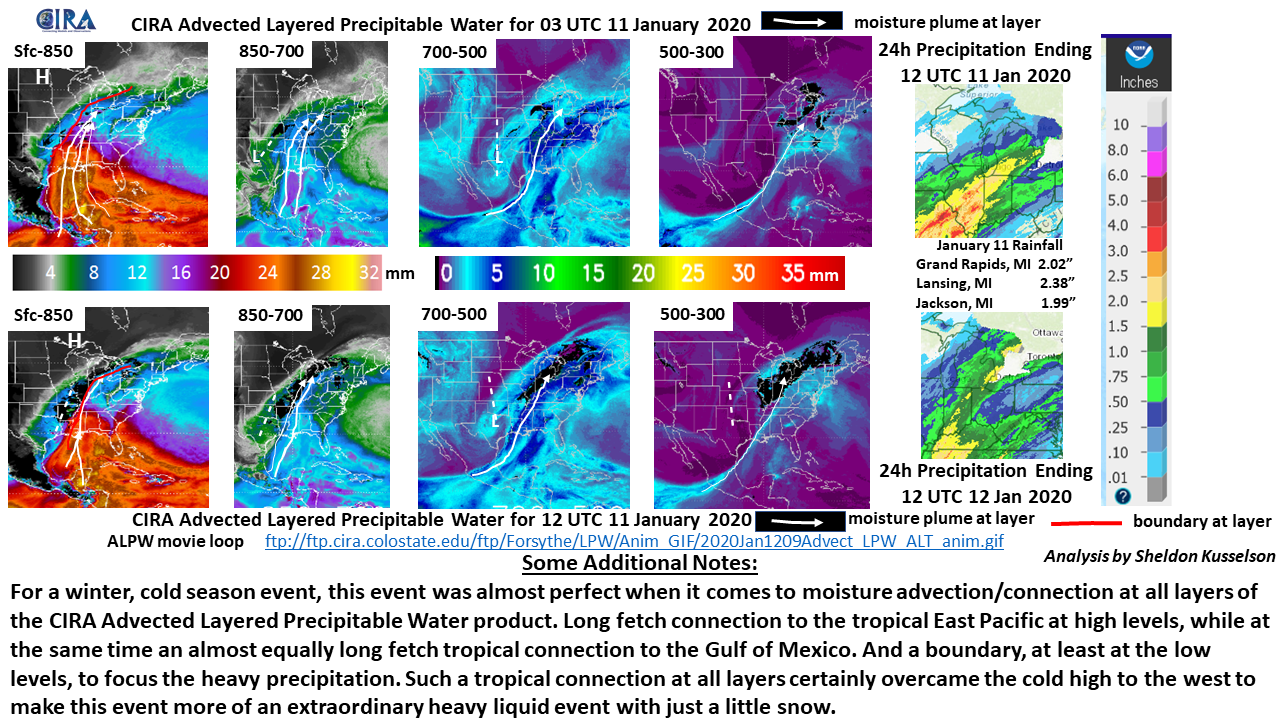

ftp://ftp.cira.colostate.edu/ftp/Forsythe/LPW/Anim_GIF/2020Jan1209Advect_LPW_ALT_anim.gif

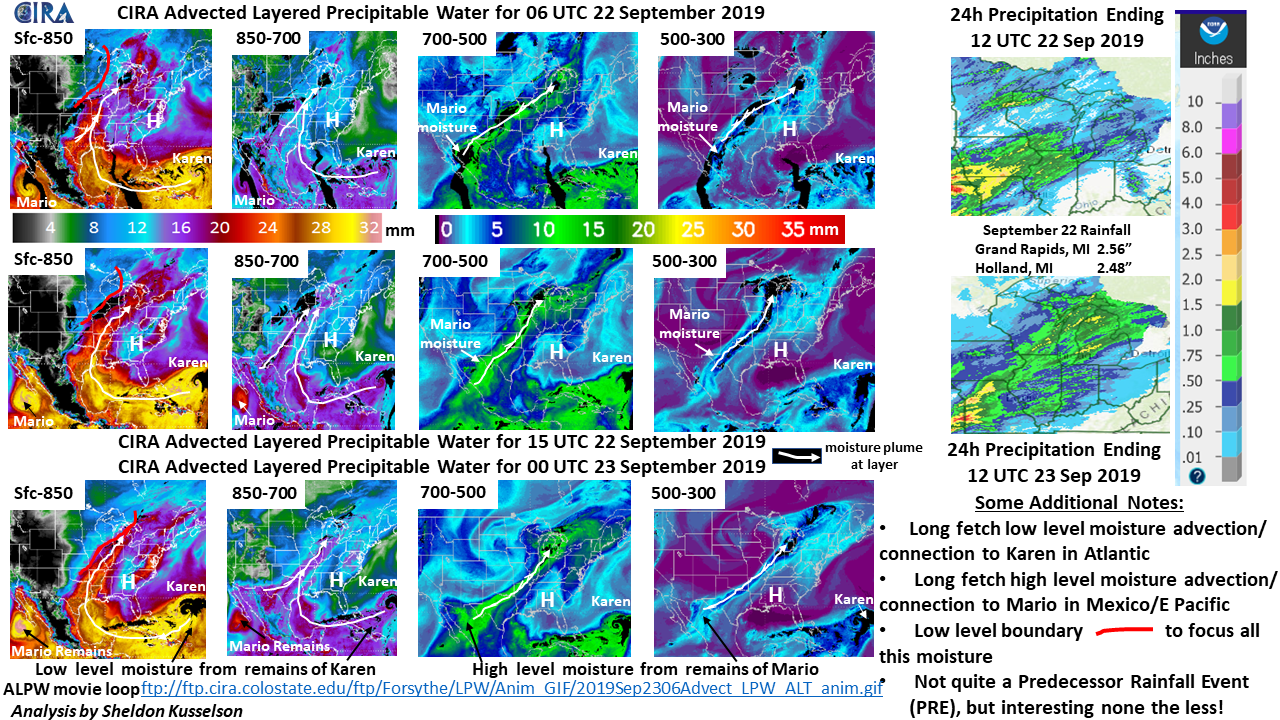

ftp://ftp.cira.colostate.edu/ftp/Forsythe/LPW/Anim_GIF/2019Sep2306Advect_LPW_ALT_anim.gif

Posted in: Heavy Rain and Flooding Issues, Hydrology, | Comments closed