GOES-16 Split Window Difference Precursor to Convective Initiation

June 12th, 2018 by Dan BikosThere are two GOES-16 products related to convective activity. One is related to convective initiation; that is, this product will identify new cumulus that will further develop into mature thunderstorms. The second product identifies which mature thunderstorms have a high probability of producing severe weather. However, both GOES-16 products require active cumulus development. We seek to fill a void by providing a product that aids in the identification of future convective initiation in a clear sky scene. The purpose of this blog entry has 3 parts: 1) training, 2) two case studies, and 3) both color and gray-scale enhancement tables, applied to GOES-16 split window difference product.

A common goal of the both VISIT and SHyMet programs is to provide training to WFO, CWSU, and National Center forecasters. One way to provide training information to these users is through the use of readily accessible information that appears on this training blog. Previous blog training has focused on a variety of weather events; for example, winter weather, severe convection, tropical cyclones, aviation applications, and fire weather. In this blog entry two case studies that focus on precursors to convective initiation are discussed.

Although there has been somewhat of a lack of severe convection during spring of 2018, two cases have been identified to highlight the use of the split window difference product in the identification of precursors to convective initiation. They occurred on 15 and 29 May 2018 both in the Texas panhandle. On 15 May 2018 a slowly moving outflow from previous convection interacted with a low-level convergence boundary. In contrast, 29 May 2018 focuses on a dryline / cold front interaction event. As a reminder to the reader, the split window difference product aids in the identification of where cumulus may first develop within clear sky conditions. We urge the reader to exercise caution in that the use of this product is inappropriate for the identification of severe thunderstorms. One significant challenge is the development of a satellite enhancement table to highlight features of interest.

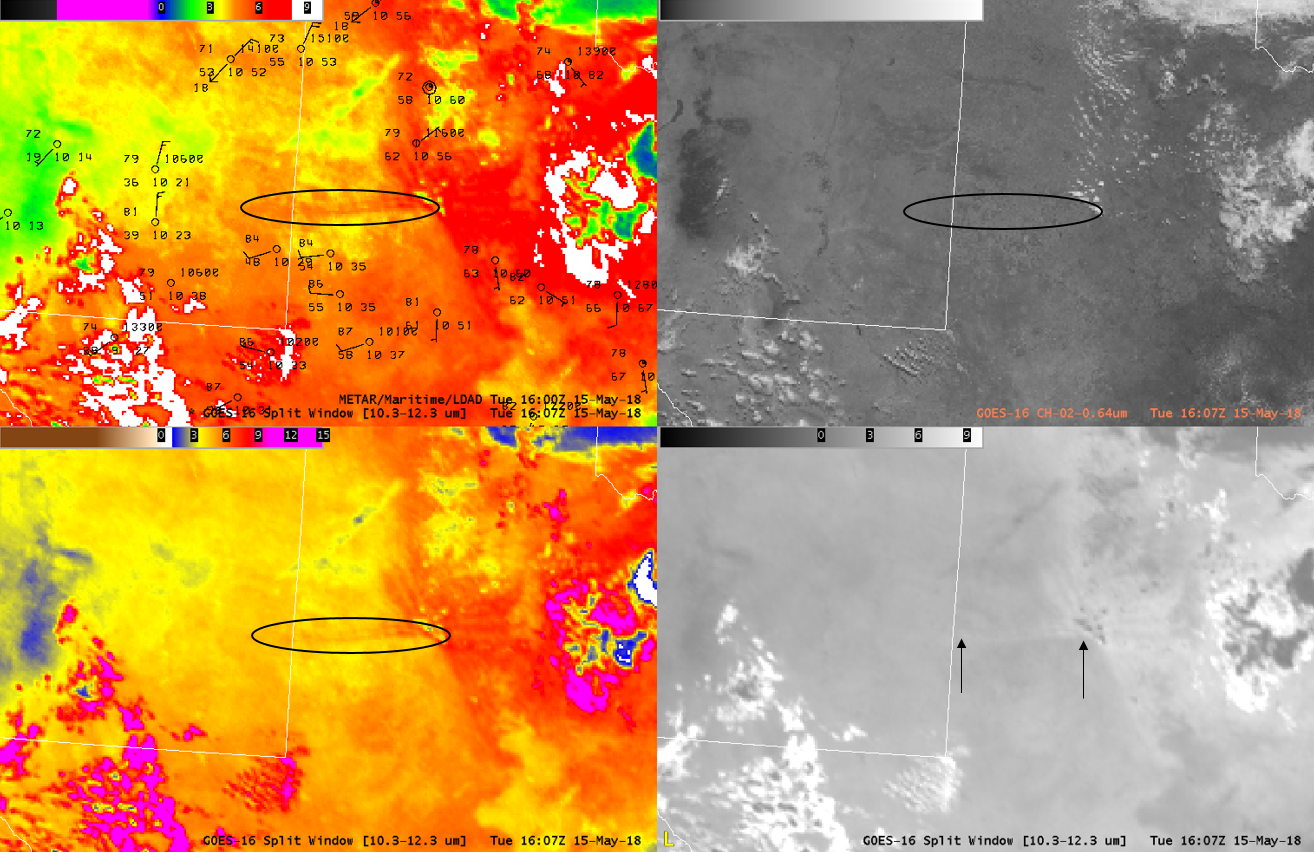

To begin with, the 15 May 2018 case will be used to illustrate modification of satellite enhancement tables. Even though a default color table exists for the split window difference product in AWIPS, we will demonstrate the usefulness of modifying satellite enhancement tables. An example image is taken at 1607 UTC, see image below:

A black oval is used to denote the clear sky precursor signature in both images on the left side. Within the gray-scale image, two arrows are used to denote the western and eastern edges of the signature. An oval was not used due to variations in visual perception, i.e., the precursor may not be apparent to some people if a black oval is used. Note in particular the lack of clouds within the oval in the visible image located in the top right panel.

To illustrate the utility of the 3 types of enhancements, the following GOES-16 animation is provided:

Top Left panel: Split Window Difference (10.3 – 12.3 micron) product in the range of -10 to +10 Celsius with the CIRA SLIDER enhancement (http://rammb-slider.cira.colostate.edu/?sat=goes-16&sec=conus&x=5000&y=5000&z=0&im=12&ts=1&st=0&et=0&speed=130&motion=loop&map=1&lat=0&p%5B0%5D=35&opacity%5B0%5D=1&hidden%5B0%5D=0&pause=0&slider=-1&hide_controls=0&mouse_draw=0&s=rammb-slider) overlaid with METARs.

Top right: Visible (0.64 micron)

Bottom left: Split Window Difference (10.3 – 12.3 micron) product with the default AWIPS color table, in the range of -15 to +15 Celsius.

Bottom right: Split Window Difference (10.3 – 12.3 micron) product with the gray-scale linear enhancement on AWIPS in the range from -10 to 10 Celsius.

The point of the animation is to provide the reader an opportunity to view different enhancements at once. Of importance are the variations in both the ranges and colors / gray-scale used for each split difference produce panel. To some, the top left may be preferred while others may prefer the bottom right and yet some will show preference to the bottom left. One key aspect to keep in mind is that the precursor signature corresponds to clear skies in the visible imagery prior to approximately 1700 UTC.

For completeness, a brief physical explanation of the split window difference signature now follows. Water vapor in the boundary layer is an absorbing gas to energy at 10.3 and 12.3 microns that is emitted from the earth’s surface. Water vapor absorbs more energy at 12.3 compared to 10.3 microns; therefore, when the temperature decreases with height the brightness temperature at 12.3 microns is less than the brightness temperature at 10.3 microns, hence the difference is positive. Along convergence zones, water vapor is transported upwards, making the moist air relatively deeper compared to its surroundings and thus amplifying the channel difference.

Another example of a gray-scale enhancement highlights the usefulness of modifying the range of the split window difference product. For clarity, the gray-scale loop on the bottom right in the previous animation is repeated along with a modified range (from 1.7 to 10 Celsius):

This example illustrates the use of changing the scale from -10 to 10 Celsius (top) to 1.7 to 10 Celsius (bottom) while preserving the same enhancement table (linear). One consequence of decreasing the range of 1.7 to 10 C is to increase the contrast. The motivation is to provide the reader with another example of how the data can be displayed. That is, some may prefer the top loop while others may prefer the bottom.

Finally, a larger version of the upper left loop of the 4 panel animation above is shown here as another way to view the data:

The 29 May 2018 case focuses on convective initiation in the northeast Texas panhandle as shown in this animation:

Top Left panel: Split Window Difference (10.3 – 12.3 micron) product in the range of -10 to +10 Celsius with the CIRA SLIDER enhancement (http://rammb-slider.cira.colostate.edu/?sat=goes-16&sec=conus&x=5000&y=5000&z=0&im=12&ts=1&st=0&et=0&speed=130&motion=loop&map=1&lat=0&p%5B0%5D=35&opacity%5B0%5D=1&hidden%5B0%5D=0&pause=0&slider=-1&hide_controls=0&mouse_draw=0&s=rammb-slider) overlaid with METARs.

Top right: Visible (0.64 micron)

Bottom left: Same as top left, except the range has been changed to -5.1 to +10 Celsius.

Bottom right: Split Window Difference (10.3 – 12.3 micron) product with the gray-scale linear enhancement on AWIPS, except the range has been modified to 0.9 to 10 Celsius.

In general, upper level cirrus clouds are seen stream from west to east from eastern New Mexico over the Texas panhandle into southwest Oklahoma. The moisture gradient associated with the dryline is shown with red colors on the moist side and green/yellow/blue colors on the dry side (note the eastward movement of the moisture gradient just south of the cirrus in the southern Texas panhandle). Followed by convective initiation in the northeast Texas panhandle around 2000 UTC.

The technique for modifying the range on the bottom 2 panels in AWIPS is as follows:

Hold down the right mouse button on the split window difference product, choose colormap.

A GUI will appear titled “Set Color Table Range”, scroll the Min bar until the contrast on the imagery is to your preference.

The above technique applies in general in modifying the enhancement and/or data range.

Further information:

FDTD GOES-16 Applications webinar on the Split Window Difference

Posted in: Aviation Weather, Convection, GOES R, | Comments closed

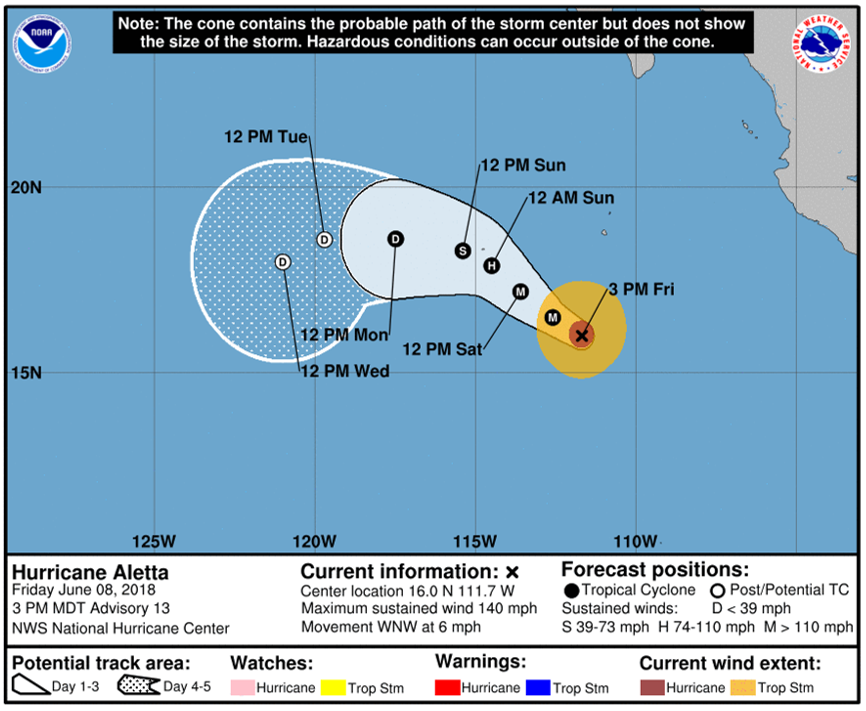

Hurricane Aletta

June 8th, 2018 by Jorel TorresHurricane Aletta has grown tremendously over the past 24 hours, and it is now determined as a Category 4 hurricane, as of this morning, 8 June 2018. Aletta is currently located southwest of Mexico, in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Aletta is moving northwestward, and is forecasted to drop in intensity by the weekend, as the system moves into higher wind shear, colder sea surface temperatures and decreasing ocean heat content. Aletta is quite large in areal extent, where preliminary reports had the ‘eye’ of the storm at approximately 20-miles in diameter. The latest National Hurricane Center (NHC) forecast track of Aletta is seen below, valid at 3pm MDT, 8 June 2018.

Satellite imagery observing Hurricane Aletta is also provided. Below is the Advected Layered Precipitable Water (ALPW) product at 18Z, 8 June 2018, highlighting the areal extent and the moisture profile of the hurricane. Product is derived from a Microwave Integrated Retrieval System (MIRS), derived from polar-orbiting satellites, and is at a 16-kilometer resolution.

The ALPW product identifies, where the moisture is predominately concentrated within four layers (i.e. thicknesses) of the atmosphere: surface-850mb, 850-700mb, 700-500mb, and 500-300mb. In the image below, the color bar is uniform across all layers, where 0-3 inch precipitable water values are seen. For this event, the majority of the precipitable water is found near the surface, where precipitable water values are ~1 inch (orange, red colors), and values decrease aloft. Black colors within Hurricane Aletta, indicate ‘missing data’, where microwave retrievals can be made within cloudy regions, however, not through areas of precipitation.

Additionally, here is the latest RAMMB-SLIDER satellite imagery of Hurricane Aletta, using GOES-16, 0.64um, visible satellite imagery near 21Z, 8 June 2018. Click on the following animation.

For the latest updates on Hurricane Aletta, click the following link.

Posted in: Tropical Cyclones, | Comments closed

Storm-relative animations for right-moving and left-moving storms

June 8th, 2018 by Dan BikosThis blog entry will compare traditional satellite animations of right-moving and left-moving storms with storm-relative animations as observed by GOES-16 visible imagery in AWIPS with the Feature Following Zoom tool. Also, comparisons will be made between different temporal resolutions, that is, AWIPS CONUS 5-minute versus mesoscale 1-minute sectors.

We will start with the traditional satellite animation which is for the 0.64 micron visible band CONUS sector (5-minute):

In the eastern Texas panhandle, we observe a storm that turns right (towards the southeast) as it intensifies. Meanwhile, in the northeast Texas panhandle into the Oklahoma panhandle we see a left-moving storm moving northeastward that appears to be moving faster than the right-moving storm.

Compare the animation with a storm-relative animation centered on the right-moving storm (CONUS sector):

and also compare with a storm-relative animation centered on the left-moving storm (CONUS sector):

How does the storm-relative animation affect your interpretation of the satellite imagery? What can you see more effectively in the storm-relative animations?

Fortunately, on this day a Mesoscale sector covered the region of interest, allowing us to make further comparisons with 1-minute temporal resolution imagery.

First, the traditional satellite animation for the Mesoscale sector:

Compare the animation with a storm-relative animation centered on the right-moving storm (Mesoscale sector):

and also compare with a storm-relative animation centered on the left-moving storm (Mesoscale sector):

How does the storm-relative animation affect your interpretation of the satellite imagery? What can you see more effectively in the storm-relative animations?

Summary:

The storm-relative animations definitely allow the user to more effectively analyze features at cloud top (overshooting tops, cloud motions, gravity waves). Features in the vicinity of the storm may be viewed more efficiently as well (clouds moving into the storm, such as potential inflow feeder clouds). Also, the storm motion relative to a boundary can be visualized more readily. This can be particularly useful in situations where you are monitoring storms that may go more parallel or perpendicular to a boundary with obvious consequences on storm intensity.

Storm speed can be seen in a relative sense as well, in this case we adjusted the loop speeds to make them look more favorable, but you may change the loop speed so that they are all the same to prove to yourself how much faster the left-moving storm is moving relative the right-moving storm. At the end of the URL, the loop_speed_ms= parameter can be edited to your preference, see what effects the same number (i.e., loop_speed_ms=20) has.

Posted in: AWIPS, GOES R, Satellites, Severe Weather, | Comments closed

Volcan de Fuego, Guatemala erupts again!

June 4th, 2018 by Jorel TorresYesterday, Volcan de Fuego erupted again in southern Guatemala. The pyroclastic flow of Fuego surprised many, and as of this morning 4 June 2018, at least 25 people have died, while many others are injured. Locals near Fuego, are in the process of being evacuated from the area.

Fuego erupted around 18 UTC, 3 June 2018, ejecting hot gas, smoke and ash in the atmosphere, where geostationary and polar-orbiting satellites observed the phenomena. Below is a video of the volcanic eruption, utilizing the CIRA-GeoColor satellite imagery from RAMMB-SLIDER, between 18-21 UTC, June 3 2018. Notice the rapid volcanic plume (brownish cloud) that develops and is advected eastward, within the time-frame.

The Suomi-National Polar-orbiting Partnership (SNPP) satellite also observed the volcanic plume. The Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) True Color and Imagery Band 5 (11.45um, brightness temperature) both show static images of the events at ~19 UTC, 3 June 2018. Static images are taken approximately 1-hour after the volcanic eruption started. Both images are courtesy of the NASA Worldview data archive website.

VIIRS True Color Imagery

VIIRS Imagery Band 5 (11.45um, brightness temperatures)

For the latest updates on Fuego de Volcan, click the following link.

Posted in: Volcano Weather, | Comments closed

Ute Park Fire, New Mexico

June 1st, 2018 by Jorel TorresThe Ute Park Fire initiated and has erupted over the past 24 hours. As of this morning, 1 June 2018, the fire has burned over 8,000 acres and is at zero percent containment, forcing mandatory evacuations. The fire is located in Ute Park, NM and is east of Eagle Nest, NM. Several structures have already been burned, and the cause of the fire is under investigation.

The Ute Park Fire and the Buzzard Fire (that has been burning for several weeks) can be seen in an array of satellite products and imagery, below.

The Near-Constant Contrast (NCC), a derived product of the Day/Night Band (DNB), utilizes a sun/moon reflectance model to illuminate atmospheric features during the nighttime, such as emitted (i.e. wildfires, city lights) and reflected (i.e. clouds) light sources. The emitted light from both fires can be seen in the NCC product below, along with the emitted city lights. Product is at 750-m resolution and image is taken at 0818 UTC, 1 June 2018.

In complement to the NCC, the GOES-16 3.9um, infrared satellite imagery is used to identify the ‘hotspots’ of the fires. In the imagery, brightness temperature values are high, expressing over 90 degree Celsius temperatures for the Ute Park Fire. The Buzzard Fire expressed lower brightness temperature values at this timestamp. Product is at 2-km resolution and image is taken at 0817 UTC, 1 June 2018.

Both fires are seen in the CIRA-GeoColor Product as well, highlighting the smoke from both fires. Video animation is taken between 15-16 UTC, 1 June 2018.

Now where is the smoke from the fires going to go? Utilizing an experimental High-Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) Smoke Model, two forecast products can be used to potentially determine where the smoke is going to go. Both forecast products are the Near-Surface Smoke (expressed in micrograms per meter-cubed) and the Vertically Integrated Smoke (expressed in milligrams per meter-squared). Both products, seen below, are utilizing the 12 UTC run, valid at 00UTC 2 June 2018.

Near-Surface Smoke (below) determines the fire emitted Particulate Matter (PM2.5, also known as ‘fire smoke’) concentrations at approximately 8 meters above the ground.

Vertically Integrated Smoke (below) simulates the total PM2.5 mass within vertical columns over each model grid cell. Vertical columns are approximately 25-km above the ground. Product incorporates the smoke within the boundary layer and aloft, displaying the integral effect of ‘fire smoke’ throughout the atmosphere.

For more updates on the Ute Park Fire, click the following link.

Posted in: Fire Weather, | Comments closed